One topic that’s sure to spark a brisk discussion among fans is anime translations, and what represents translators taking undue liberties with the original dialogue in an anime to “improve” it. The current season has seen quite a few creative approaches to translating the anime we all love, which has caused pushback by fans. In this post, let’s look at what represents a “bad anime translation” and how I’ve approached translating over my own career!

Why Are Fans Complaining About Bad Translations This Season?

We got some really interesting anime series this season, including the story of a boy who finds himself trapped in a dog’s body. It’s a strange show, but made slightly more bizarre because of some of the choices the translator made, adding meme-esque dialogue like “yeeted”, “resting bitch face” and “eye bleach,” and making some questionable translation choices. For example, they chose language that made the gal Nekotani seem like a dumb “bimbo” when that was not in the original text.

Bad anime translations are a topic fans can get touchy about quickly. In an episode of The Rising of the Shield Hero, the translator replaced Raphtalia’s original line of “I won’t allow [you to harm Filo-chan]” with “Not on my watch!” which could represent a translator adding something to the work that wasn’t there. While this isn’t all that bad, when I tweeted about it I got hundreds of replies, as fans chimed in on either side of the topic.

Are Bad Anime Translations Always Political?

We always project our concerns onto everything around us, and all too often perceive any variation from our own worldview as a sinister plot by the opposition to tear down the fabric of society. A few years ago, a Funimation localizer changed Lucoa’s line of “everyone was always saying something to me, so I decided to tone [my sexy clothing] down a bit” to “oh, those pesky patriarchal societal demands were getting on my nerves, so I changed clothes.” This caused many to assume that any change made to any anime work for any reason was due to “wokeness,” which isn’t always the case.

The issue is whether a given anime, manga or game from Japan should be “translated” (representing the original work in English as accurately as possible) or “localized” (reworking it to be more appropriate to a new market overall). How do you feel about this?

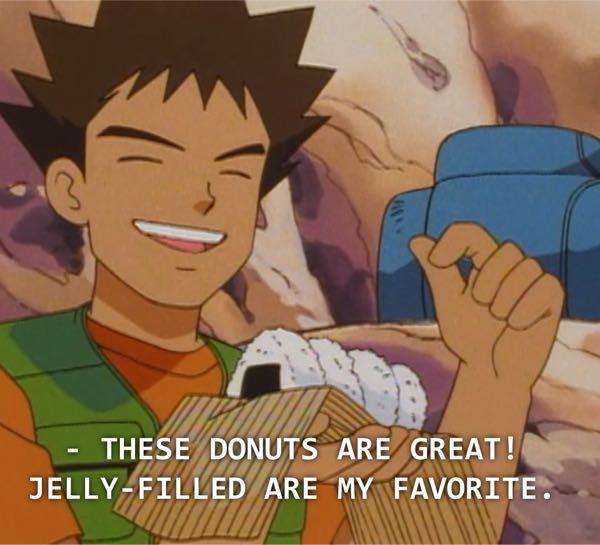

While most people following J-List are likely to be mature fans who want as few changes to a work as possible, you can’t argue that Pokémon would have been less successful internationally if it had been translated with 100% faithfulness, with all Japanese names left in place and “jelly-filled doughnuts” accurately represented as onigiri rice balls…despite no one knowing what those were back in 1997. So I can appreciate both sides.

The Ernest Hemingway Approach to Translation

When I founded JAST USA back in 1995 to translate visual novels into English, I didn’t realize what a long journey I’d be going on as a translator. Early on, my policy was that “the translator should be seen and not heard,” with the goal being that customers can enjoy a visual novel without realizing I’m there.

As a translator, I was influenced by reading the novels of Ernest Hemingway, who often has his American characters speaking Spanish, Italian or French. You know characters are speaking a foreign language because the text becomes absolutely generic, devoid of any colloquialism that could only exist in English, indicating that this part of the story is taking place in another language.

Here’s how I try to approach a translation:

- There is a “fit” for any given line of Japanese into English that I strive to find. Oddly, the act of translation itself is not done by my conscious mind, but one layer down in my subconscious. It takes about 1.5 seconds for a translation to be ready, and I can almost hear a ding! sound when it’s finished “cooking.”

- Decisions must be made about how to map certain words, and should always be standard across that work. In terms of the hentai visual novels I work on, one thing I have to establish is how I’ll translate the words for genitals. I usually keep things generic, using “cock” and “pussy” unless there’s a special case in the text. (Japanese naughty words are famously bland compared to English.)

- How should Japanese honorifics be handled? In my own case, I always preserve name suffixes like -san, –chan and -senpai because they’re important markers for how the characters feel about each other. I wouldn’t require this from another translator, however.

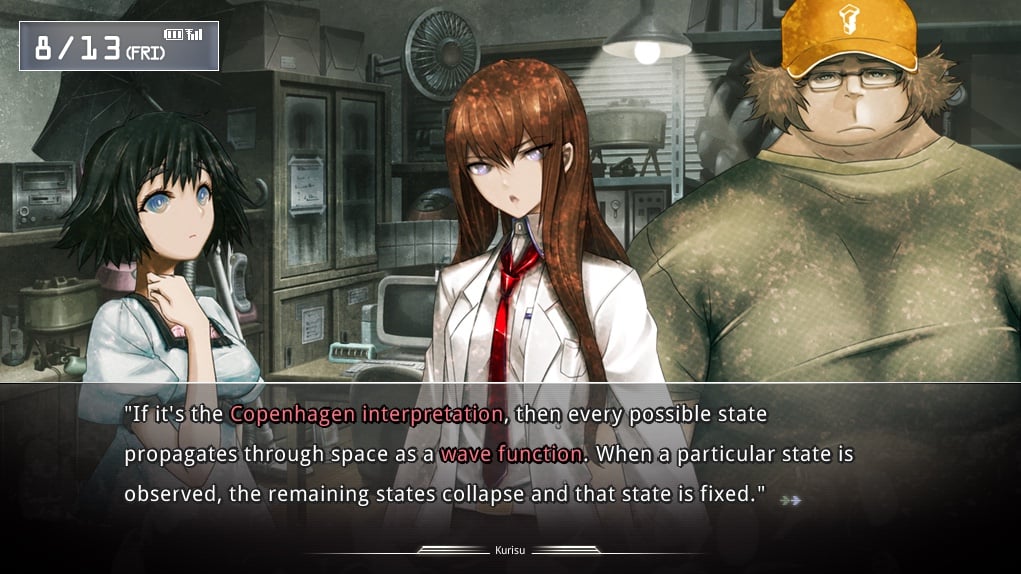

- In a challenging game like Steins;Gate, there are lots of new terms like Phonewave (name subject to change). As long as each term has been chosen thoughtfully and uniformity is maintained, anything will probably work.

- And yet, if there’s an existing translation that fans have embraced, it’s smart to go with that. When the Lord of the Rings films came out, legendary “queen of movie subtitles” Natsuko Toda translated the films without referring to the Japanese versions of Tokien’s novels. But when fans already have settled on a translation for “not lightly do the leaves of Lórien fall,” having her translate everything from scratch brought a lot of anger.

(I did some googling on the individual who did the translations. When fans hassled her on Twitter for changing the intent of some of the lines in the anime, she responded that “this isn’t for you,” presumably meaning advanced fans who get spicy about mis-translations. And yet, she loudly complained about having to look at sexy girls in bikinis in Shonen Jump, despite this magazine clearly being aimed at males age 14-35…making the entire genre “not for her.”)

How Does J18 Publishing Approach Translation?

No matter how anal I might or might not be about the subject of anime translations, there’s a person who’s 100x more extreme than me on this topic: David Goldberg, managing editor of all works by J-List sister company J18 Publishing. If you’ve (hopefully) read some of the 100% uncensored doujinshi and tankoubon-format manga they release, you’ll know how seriously they take things, from each speech bubble to meticulously re-drawing the sound effects to match the English versions.

On the question of getting overly creative on translations, David’s response was:

The approach we take can be summed up in two words: Radical Equivalence.

TL;DR: it doesn’t so much matter what specific words were in the Japanese source as what the author was trying to say with them, so when someone reads our English translation, they should have the opportunity to feel the same way a Japanese reader does.

And sometimes this means memes, when they’re appropriate. Japan has memes too!

(If you want to talk hentai translations with the J18 staff, why not join their excellent Discord server?)

J-List Customers Give Their Opinions on Bad Anime Translations!

Bad anime translations are like the universal definition of obscenity: “I know it when I see it.”

Any anime, manga, or video game from Japan must be accurately translated into any new language.

An official translation is different from fansubs, which can have fun with the material. It’s supposed to represent the creator’s work to fans around the world.

Isn’t changing the original text and adding your own ideas the definition of ‘cultural appropriation’?

Thanks for reading this blog post exploring bad anime translations, and how we’ve approached translations in the long history of J-List, JAST USA and J18 Publishing. How do you react to “overly creative” subtitles in anime? Tell us below, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, or TikTok!

J-List loves to make anime and hentai real for you, and now there’s a full-sized oppai toy for fans of Marie Mamiya, from the Sleepless and Starless games. The new toy is compatible with the larger version of the Oppai Board system from Tamatoys, making it just like touching her boobs for real! Browse all Sei Shoujo official hentai products here!