The recent news regarding staff leaving studio MAPPA over being poorly treated has once again brought the peculiar state of the anime industry into the spotlight. Few people doubt that it’s a global juggernaut and an enduring symbol of Japanese pop culture. At the same time, it’s also burdened with long-standing tensions, alongside a notorious reputation regarding poor work conditions. Yet as high-profile as these issues can be, they’re nothing new.

Even amidst a Golden Age full of hits and brilliant works, such sobering problems hint at the industry’s seeming decline, if not collapse. This begs two questions: how did it come to this and are there any efforts being made to improve the industry? The truth is much more complicated.

A Checkered Track Record

The origins of these woes are the subject of debates and heated blame games. Nonetheless, part of the answer can be found in the so-called “Curse of Osamu”: a term used to describe how Tezuka himself sought to capture the television market in the 1960s through animated works that could be cheaply made. It also had a less stellar – and in all likelihood, an unintentional – legacy in discouraging competitors that didn’t match his inexpensive “dumping”, with creators instead opting to produce works for less just to keep up. Coupled with the emergence of the Production Committee system – an investing and risk-management arrangement created following the financial failure of Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro (1979), with a persistent lack of profit sharing and bonuses – highlighted by J-List’s own Peter Payne, the result is a “norm” that’s steeped against animators.

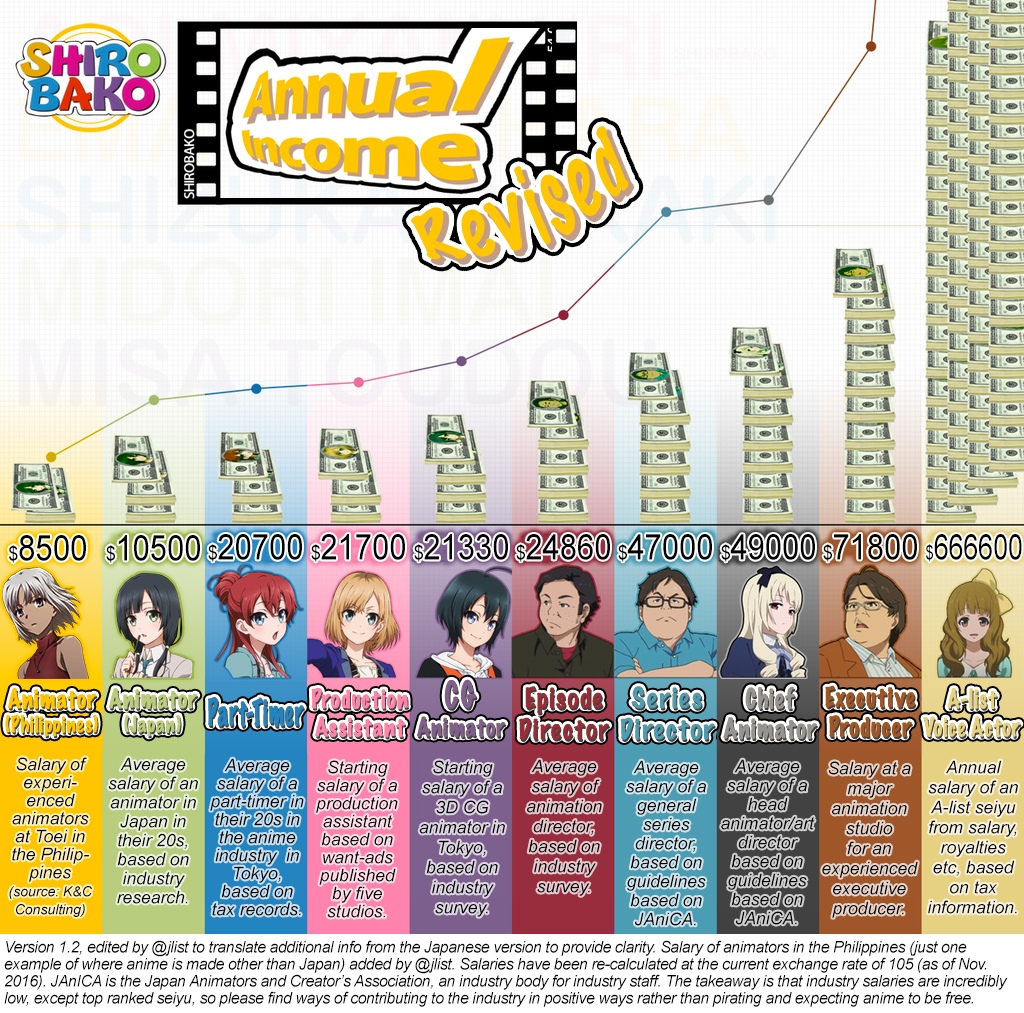

Whether it be studios outsourcing work to South Korea in the ‘80s to maximize production, or their penchant for hiring foreign and online freelancers (including volunteers through social media) on similar grounds, the Osamu curse still continues to leave deep echoes now. Cost-cutting is especially evident in the industry’s much-maligned working conditions. Although JAniCA’s 2019 fact-finding survey noted that animators, in general, had an average annual salary of 4.4 million yen ($40,700), in practice this value can be wildly disproportionate. Around 40% of respondents, corresponding roughly to younger staff and animators, earned less than 3 million yen ($28,000) annually. Moreover, animators, including producers, tend to work about 230 hours a month, or around 11.5 hours a day. Combined with the high cost of living, especially around Tokyo, it paints a sobering light on the recurring comments of how some feel burdened by heavy workloads or are bitter about getting so little for doing so much. Even Makoto Shinkai reportedly got around 20 million yen ($200,000), in spite of Your Name (2016) being a box office hit, due in no small part to the status quo.

Unsurprisingly, these have fueled many horror stories and accompanying gloomy headlines over the decades. Take A-1 Pictures being nominated for the ignoble 2014 Burakku Kigyou (“Black Company”) Awards over an overworked employee’s suicide, or recurring fears of Chinese companies enticing disgruntled animators to work for them.

This isn’t just a problem in Japan, it’s a global one. There are disparities in salaries and working conditions across company, regional, and national lines. An animator working in New York City, for example, could earn as much as $110,000 annually, while an equivalent position in Los Angeles would only get $48,000, which doesn’t account for varying standards of living. Another example is the generally low pay Filipino artists receive for doing outsourced work on behalf of studios (including Japanese ones). As tempting as it may be to find cheap slogans and quick answers, this conundrum defies clear-cut solutions.

Still, though it’s the anime industry’s worst-kept secret by this point, you can’t help but feel disheartened by such news. To say that the industry is dying or doomed, however, is no more accurate than saying that there’s nothing wrong.

Always a Silver Lining

As attention-grabbing as such gloom can be, there’s a less-covered flip side. If the Association of Japanese Animators’ 2020 report is anything to go by, the pay gap isn’t just affected by “unanticipated” market growth, record sales in spite of COVID-19, or any of the common issues you might expect. Just as profits rose over the 2010s, so have unit production costs. Coupled with technological shifts (such as online distribution overtaking TV networks), these have prompted the industry — alongside prodding from the Japanese government – to take reform more seriously. While the pandemic may have likely accelerated it, this has manifested in a more pronounced push among companies towards reviewing work conditions and employment norms. Meanwhile, the same 2019 JAniCA report noted that average annual salaries were slightly higher than others in the private sector. They’re also a significant improvement overall, compared to 2009, when dwindling talent pools were even more severe, and an average animator earned only 2.14 million yen (US $22,600) a year.

More than about resilience and making classics, the history of Kyoto Animation is also one of slyly breaking away from the industry “norm”, inspiring if not influencing other studios in the process. Circa 2020. (Source: YouTube)

Some studios and creators, however, have gone the extra mile. Kyoto Animation, for instance, rightfully deserves credit for its notable in-house production system, an almost familial work philosophy, and a dedicated training program, the latter contributing to its persistent recovery following the tragic arson of 2019.

Ufotable has also followed a similar path (complete with its own school), while Studio Bones’ leadership is prioritizing both decent conditions and its staff’s well-being, as though trying to avoid MAPPA’s mistakes. Which isn’t to ignore WIT Studio collaborating with Netflix over an initiative to help fledging animators flourish, Cygames using funds from mobile gaming as an alternative to the status quo, or Jun Sugawara’s ambitious crowdfunded campaign to help struggling employees. Granted, such initiatives and developments either happen sporadically or could take years to bear fruit. Cynics may even argue that the likes of KyoAni can get away with it due to being higher up the Production Committee tiers compared to others. Nonetheless, it seems like the Curse of Osamu, however gradually, may be on borrowed time.

In spite of difficulties, including the challenges of COVID-19, Sugawara and Anime Dormitory’s project remains in high gear, and in good spirits. (Source: YouTube)

Even setting aside the old adage of how “bad news sells,” chances are we’re not as likely to notice such positive trends. Then again, there’s a grain of truth in the hyperbolic pessimism seen at times in discussing the anime industry. What happened in MAPPA won’t be the last time such sobering headlines come down the wire. Yet, to declare anime dead is far too premature. You need only dig a little deeper, as there’s always a silver lining.