As the old French saying goes, the more things change, the more they stay the same. This is particularly true whenever anime or manga is discussed. Chances are, you’ve recognized it as the proverbial “Nostalgia Filter,” if not fallen prey to it yourself.

No one could really say for certain when this actually began. Still, it doesn’t take much to find such talk online and off. Whether it’s how anime used to be better in the past, how everything nowadays seems to be the same, or the sentiment of “Anime is dead/dying” that pops up every year, the variations are legion. Yet, just because this keeps popping up almost regularly doesn’t mean that there’s no point responding back.

If anything, the rebuttals can be just as numerous.

“The good old days”

It’s been said far too many times by now that anime in the “good old days” was plain better. Works as varied as Akira (1988), Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995-96), and much of Hayao Miyazaki’s portfolio are likely to be brought up in forum threads. Inevitably, however, you’d be asking yourself: when were those old days?

As noted by Spanish artist Kukuruyo, it’s (among other things) completely in the eyes of the beholder. What constitutes as “old” can be very fluid, at times dependent on when fans were first exposed to Japanese works. This could mean anytime over the past 40-50 years, wherein the first iteration of Astro Boy (1963-66) can be lumped in with something like Akira or more recent fare, like Code Geass (2006-08). That the resulting lists would also be incredibly subjective drives the point home.

Granted, choosing examples from such an absurdly broad selection is made easier by the Nostalgia Filter’s penchant of sorting out the chaff. You’re more likely to call to mind Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam (1985-86) than the kids-oriented shows more common on TV during that decade. Unless it’s something memorably good, or laughably bad like Twinkle Nora Rock Me!, a good deal of anime and manga tend to be sidelined if not forgotten. This was helped along in the past by how only a relative handful of works were available for fans outside Japan. Though this trend has been diluted by the access provided by both the Internet and foreign distributors since the 2000s, alas, it’s still not unheard of to hear those old complaints resurface.

Was everything the same?

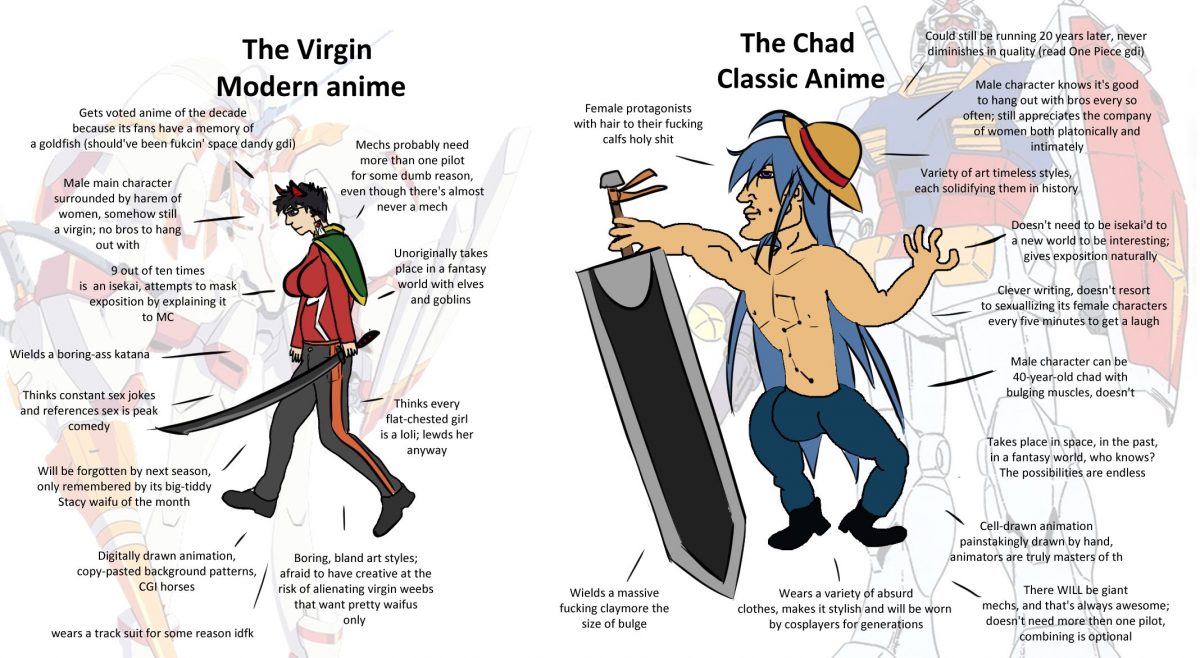

Related to hearkening back to the old days is the recurring tendency of seeing almost everything out nowadays as the same. Unlike “before”, when anime and manga seemingly had soul, it’s all moe, isekai, or whatever’s seen as trendy and “trash” in modern works. Chances are, you too may have fallen into the same trap a couple of times.

Recording of an ADV Films promotional video from 1996, showing what was popular at that point in time. Circa 2013. (Source: YouTube)

Partly, this has to do with how specifics genres and themes gain popularity in the fandom. For instance, and as highlighted by anime critic Ryusuke Hikawa, mecha (especially Super Robots) became so popular in the 1970s and ‘80s that they were pretty much everywhere, from merchandise to copycats. This would not be too dissimilar with how a slice of life shows became trendy by the 2000s, or how it became fashionable for creators to slip in characters based on Rei Ayanami. It stands to reason that every year or decade would have its own favorite flavor.

Another major cause, though, is the tendency to use limited references. Whether it’s due to seeing just a handful of works in a genre, or being familiar only with works aimed at Shonen audiences, it makes it easier to notice recurring conventions and tropes, further helped along by the Nostalgia Filter. Given enough time, this can also lead some to conclude that there’s barely anything original anymore. Even setting aside the changes from when the original Dragon Ball (1986-89) aired to My Hero Academia (2016 onwards), this falls apart upon broadening one’s palette, such as checking out more Seinen or Josei oriented content. This isn’t getting to how moe has been around since the ‘90s, while the first Macross (1982-83) helped set the stage for idol characters well into the future.

Anime is Dead, Long Live Anime

Then, there’s the more negative meme of how anime seems to be in nigh-perpetual decline. Whether it’s complaints about how overall quality has suffered compared to yesteryear, or the myriad issues (real and perceived) faced by the industry, there’s no shortage of material bemoaning a demise that’s all but taken for granted, almost like an article of faith. Even the likes of Hayao Miyazaki jumped in on it, as while he never actually said the infamous quote “Anime was a mistake,” his sentiment against contemporary, more otaku-centric trends in contrast to Studio Ghibli’s more Disney-inspired aspirations are clear enough to see.

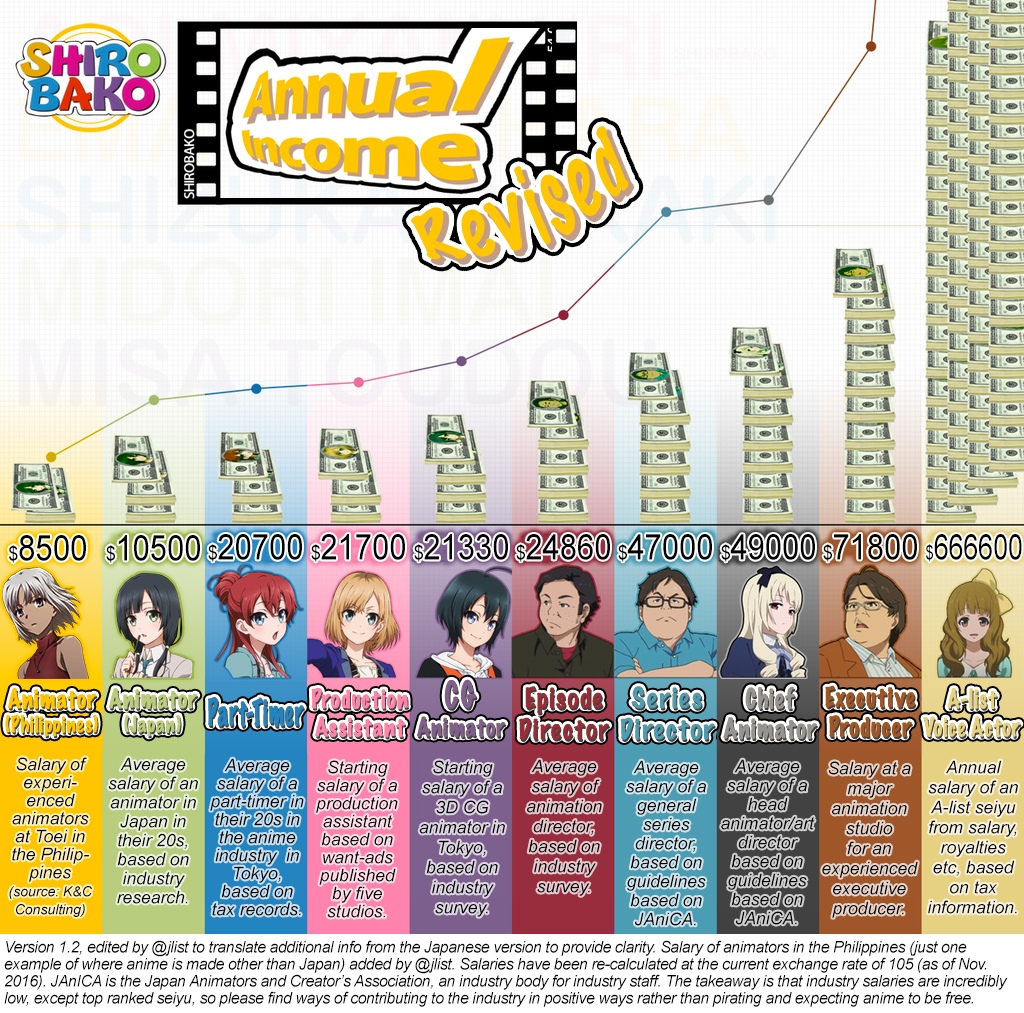

There are undoubtedly grains of truth that lend this angle a shred of legitimacy, yet these often have nuances lost. The “Curse of Osamu,” so-called due to how Tezuka himself managed to sell his material for cheap on TV in the ‘60s, also had the effect of setting an industry “norm” that would sound familiar: low budgets, similarly small salaries, and the committee system, among other issues. Setting aside how the maligned working conditions are not as universally severe as commonly perceived, these problems have thus been around (in one form or another) for decades, even during the “good old days” of Akira. This extends to other, apparently “recent” trends like outsourcing, with Japanese studios relying on such with South Korea as early as the ’80s.

Which isn’t getting to how these ignore other aspects that don’t align with the narrative. According to the Association of Japanese Animators, the industry has seen significant growth over the past decade alone. Meanwhile, you’d find that the old status quo has been changing, whether it’s the trailblazing path set by Kyoto Animation, the ascendance of Makoto Shinkai as the new generation’s Miyazaki, advances in digitization, or the continuing rise of online streaming and publishing. For all the challenges faced by Japanese creators today, there are just as many opportunities out there, if not even more than what would have been available not too long ago.

Memes that Refuse to Die

Warts and all, it’s a fascinating time to be a fan of manga and anime. Barring something truly dramatic, they’re not going anywhere, anytime soon. Still, the various memes fostered by Nostalgia Filter simply refuse to die. It seems all but guaranteed that newer generations would repeat many of the same talking points in the future, just as you might have had at some point.

Though in an ironic sense, there’s something weirdly comforting about all that. Whatever the era, some things don’t change.