Japan is, by and large, quite a homogeneous place. I’ve traveled from Sapporo to Okinawa and have seen much of the country, but except for regional differences in food, dialect and weather-dictated architecture, it’s surprising how uniform modern Japan can be. An elementary school in Tokyo is very likely to look similar to one in Niigata and Kagoshima, and things like roads are apt to be pretty much the same no matter where you go, too. It’s not like in the U.S., where culture on the two coasts can be as different as night and day, with large, easy-to-heat school buildings in Maryland and sprawling, open schools in California, and funny things called “turnpikes” in Pennsylvania (I never figured out what those were, since we don’t have them in California). In some ways, the monoculture that you see in Japan extends to the people, too. This is a country where 98% of the population seems to believe, without ever having a conscious thought on the subject, that they are of identical stock, with black hair and “black” eyes (they mean brown, but always say black for some reason). In reality, there is quite a lot of variation in the features of Japanese people: lighter colored hair, differently shaped faces, more or less body hair, eyes that are more narrow (hitoe, eyelids with one crease in them, vs futae, eyelids with two creases), and so on. While people here would be insulted if you suggested that “all Japanese look alike” to foreigners (although I’ve been mistaken for other gaijin more times than I can count), the tendency for people here to think of all Japanese as coming from the same stock is a useful social engine sometimes called the Myth of Japanese Uniformity. The idea is, since the Japanese don’t “see” differences in their own people, they can get along on a more even plane without a lot of discrimination, which is good for a country that values harmony like this one.

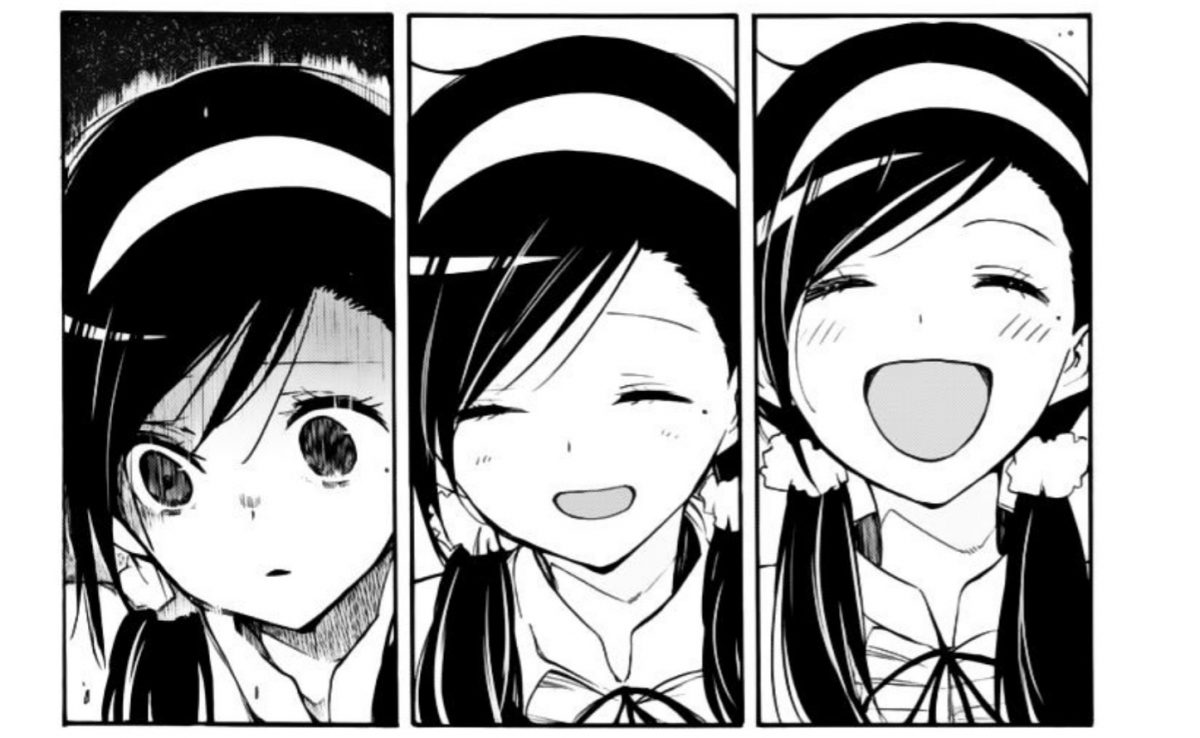

An example of hitoe, or single-crease eyelids.