I started studying Japanese at SDSU back in 1988. When a person learns a new language, they actually develop a separate personality, essentially starting out as a child in that language, playfully testing the boundaries of grammar and vocabulary just as any child does. Whenever Mrs. J-List calls me immature for something I do, my excuse is that my Japanese-speaking self is only 31 years old.

https://twitter.com/JListPeter/status/1162190023753490433

As I wrote in my long post about How I Learned Japanese, I mention that Japanese is easy to learn in a lot of ways. It has only five vowels (the same as Spanish), there’s no intonation as in Thai or Chinese, no weird grammatical structures like conditional perfect, no helping verbs, no gender for nouns, not even a difference between count and non-count nouns. There are, however, some areas that are new to English speakers, including the way Japanese have different pronouns for men and women, essentially baking gender differences into the language.

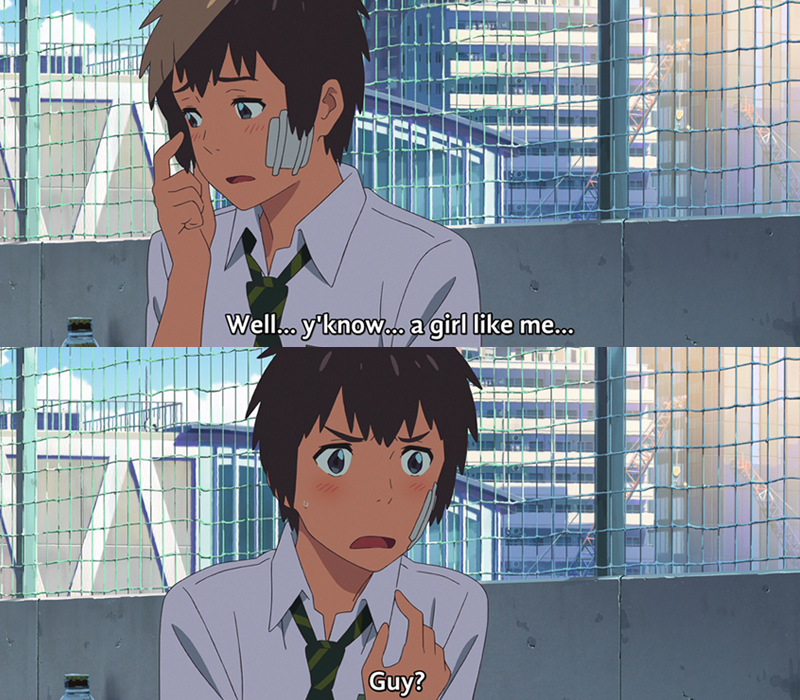

These gender pronouns are something you might or might not have noticed, if you’re watching anime with subtitles. But in the film Your Name, which I re-watched recently to get ready for Weathering With You this weekend, they become central to the plot, because of the way Mitsuha and Taki both exchange bodies at various times in the story.

The first-person gender pronouns in Japanese are:

- 私 watashi, the most basic way to say “I.” It’s gender-neutral, but women say it a bit more than men.

- わたくし watakushi, a slightly more formal version of the above. Used by both sexes in formal settings such as a job interview, but at other times by women only.

- あたし atashi, a version of the above used only by women (and Mitsuha in Taki’s body in the scene above). Some gay men will also use this word.

- 僕 boku, a polite word for males to use. It sounds slightly boring and blasé in some situations, which is why Taki’s friends become suspicious when Mitsuha tries using it. Tomboy type girls would also use boku.

- 俺 ore, a “manly” first-person pronoun, which is the one Taki finally uses in the above scene.

- 内 uchi, literally meaning “my house,” used in Kansai dialects and by Lum from Urusei Yatsura.

- Young girls will often use their own names in place of “I,” speaking in the third person, which sounds very cute.

As people go through their lives, they use pronouns that feel right for them, which is largely determined by what group of friends they feel connected to. I remember when my son, aged 4, started shyly using the masculine ore because his friends at preschool were using it, which was adorable to see. And when my daughter was 9, she started using uchi, which is rare in our part of Japan. When I asked her why she was doing it, she said, “Well I can’t very well use atashi. It’s much too cute and feminine for me!”

There are some challenges to getting these pronouns right when you’re learning. If you learn Japanese from anime you might make errors or acquire a fake dialect. Another issue is dating people of the opposite sex, since you might pick up their speech patterns, which can lead to unexpected results. When in doubt, watashi for female and boku for males will never lead you astray.

If you’re curious about second-person gender pronouns in Japanese, here’s another post.

We hope everyone is getting ready to have a great weekend. This weekend we’re having a great flash sale on all our anime goods, including officially licensed products from all your favorite shows. Get 10% off all anime goods automatically this weekend only, no code to enter! Browse them all here!