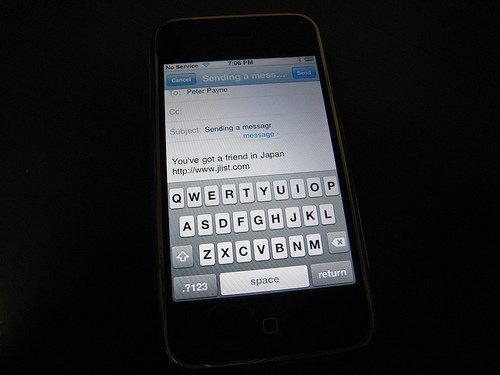

When I was in the U.S. I played with Apple’s new iPhone in an Apple Store and immediately knew I had to have one. (It’s funny how my business trips to the U.S. just happen to coincide with Star Wars movie releases, major U.S. product launches, and so on — please don’t tell my wife.) The iPhone is great, and even in Japan, where its phone functions don’t work, it’s quite useful as a WiFi device that allows me to do my mail, check websites, and enjoy music and videos. One of the big benefits of Apple’s OS X operating system is that there’s only one worldwide version, with everything international users need included on the install DVD — this is a huge improvement over the days when the Japanese version of the latest OS would take a year to show up. (The “everything on one disc” concept is yet another one that Microsoft’s Vista stole from OS X, although I don’t know if that was noticed by many people.) While the iPhone 1.0 does support many non-English languages, including the ability to display (but not input) Japanese and Chinese as well as all European languages, it seems to me that Apple will have some challenges making the device work as well as it does for English-speakers in the U.S. as it does for users around the world.

I remember a trip I made to a MacWorld Expo in Tokyo back in the 1990s. Apple was working on a Japanese version of the venerable Newton, and asked me if I’d write some kanji characters with the software they were testing. If you’ve ever thought that the Newton was hard to use with the standard Roman alphabet, it was even more difficult getting it to recognize my handwriting in Japanese, and the device was eventually “Steved” (cancelled, to use the terminology of the day) not too long after. Happily, the iPhone has an on-screen keyboard for you to type on, which works in tandem with an internal dictionary that corrects errors you make while typing, and it learns too, so that it eventually stops trying to tell me that my website is “joist.com.” Getting this dictionary just right for users in other countries will be extremely important for Apple, since no one would want their phone suggesting incorrect spellings to them as they type, and even the minor differences in the language that the device supports — supporting Canadian English as opposed to U.S. English, say — will be quite important for the iPhone’s success overall.

Inputting complex languages like Japanese will be a bit more difficult, and it will call for a “front end” input manager as seen in the built-in Kotoeri for Mac and Japanese IME for Windows. The way it works is, you select Japanese as the current input method, then type a word like “nihongo” (にほんご) and press the space bar. The front end program then guesses what kanji it thinks you want, and you keep typing or choose another character if it guessed wrong. This is usually fairly straightforward, but there are some words that have many possible kanji, like kousei (koh-SEI, in hiragana こうせい) which could mean structure (構成), justice (公正), public health (厚生), or fixed star (恒星), depending on which characters you choose. One issue that might miff would-be iPhone buyers in Japan is, there are several third-party front-end kanji input programs on the market, like EGBridge and ATOK, which offer more accurate guesses about what kanji you’re entering. If Apple requires Japanese users to use, say, the default Kotoeri input method, some will pass on the phone for that reason alone. Hopefully fear at not doing well in their second-most important language market will help Apple understand how important opening the iPhone up to developers (“…developers! developers!”) will be — Japanese iPhone users will need to be able to pick a kanji input tool that they’re comfortable with.