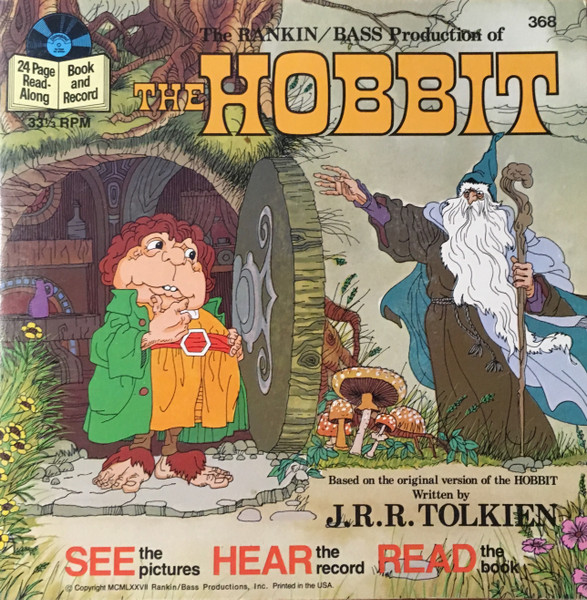

What if you were told that long before shows like the original Transformers series (1984-87) and Saber Rider and the Star Sheriffs (1987-88) were a twinkle in someone’s eyes, there were high-profile collaborations between Japanese and American creators? Among the most fascinating of these projects is the 1977 adaptation of The Hobbit. While this made-for-TV sleeper classic makes for an unlikely gateway to anime, it opened doors for both audiences and the animators who created it.

Although this 77-minute take on JRR Tolkien’s book was the brainchild of Rankin/Bass Productions, Inc., the handwork was by Tokyo-based anime studio Topcraft, overseen by its co-founder, Toru Hara. While American historians might recognize those names, given previous Rankin/Bass collaborations such as Kid Power (1972-73) and The First Easter Rabbit (1976), anime fans may find them more recognizable. While some went on to found Pacific Animation Corporation, which became Walt Disney Animation Japan, the bulk of the staff would be reorganized into Studio Ghibli.

The film’s intro shows both its faithfulness to the novel and its subtle anime footprint. (Source: YouTube)

It begs the question: is The Hobbit worth watching now, whether on its own merits or its significance for anime history? Or, is it best left to the Mount Doom of time?

Out of the Shire

The story of The Hobbit sounds simple at face value, yet is truly epic. Bringing viewers to Middle-earth, the film follows the titular hobbit, Bilbo Baggins (Orson Bean), the everyman. One day, he’s visited by the wizard Gandalf (John Huston), who seeks a companion to share an incredible journey. He’s then introduced to thirteen dwarves led by Thorin Oakenshield (Hans Conried). Bilbo finds himself dragged along on a quest to win back the dwarven treasure of the Lonely Mountains from the dragon Smaug (Richard Boone). What ensues is a grand adventure unlike any other, with an even greater tale to be told involving an inconspicuous ring found along the way.

Anyone familiar with recent adaptations may find much that hasn’t aged well. The elves, for instance, fluctuate between looking recognizably humanoid to more akin to old fairy tale book portrayals. The writing itself, when not quoting almost verbatim from the book, tends to be on the nose. Whether this is due to writer Romeo Muller’s attempts to convey a “quiet comedy of character”, or the result of making the material more child-friendly for TV, it can come off as cheesy rather than epic. This is particularly noticeable in how the film portrays the Battle of the Five Armies with a blunt anti-war motif.

That’s not ignoring what has stood the test of time. On top of serving as an effective surrogate for the audience as they’re eased into Middle-earth, Bilbo is genuinely likable and acts as we’d imagine an average person would in otherwise fantastical circumstances. Meanwhile, his companions, Gandalf, and Elrond of Rivendell are not only portrayed accurately according to Tolkien’s writings, but have proven iconic enough to influence depictions as recently as Peter Jackson’s three-part adaptation (2012-14), and even The Rings of Power (2022).

According to co-director Arthur Rankin Jr. in a 1977 interview, there’s no material in the movie “that did not come from the original Tolkien book.” This is in full display in The Hobbit. In contrast to Jackson’s effort, Tolkien fans may notice how it sticks firmly to what’s actually written in the source material without much fuss or sidetracking. Though there are still some deviations, notably the complete omission of the shapeshifting Beorn, despite his role in aiding the protagonists, the result is a streamlined plot that feels complete and self-contained. It’s not without reason, then, why some view this as one of the most faithful takes on the book ever made.

An Unexpected Anime

As recounted in the same 1977 interview, among Rankin’s influences for the visuals was the work of English illustrator Arthur Rackham, whose style coincidentally inspired Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). So, at first glance, you might be hard-pressed to recognize The Hobbit as an anime at all. Looks, though, can be deceiving.

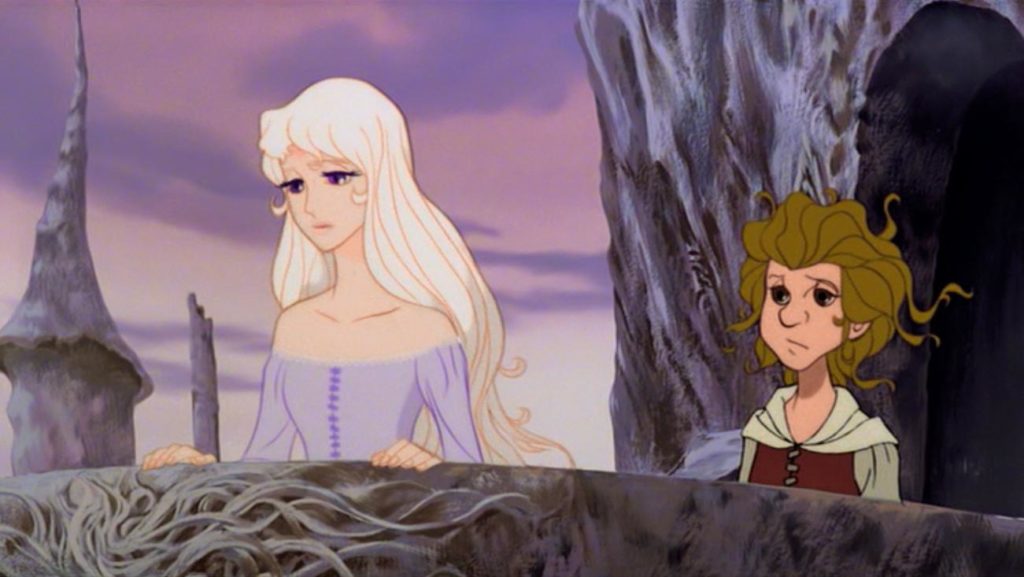

Topcraft’s handiwork is undoubtedly solid all throughout the film, with crisp attention to detail, vibrant colors, and a distinct aesthetic that matches up with Tolkien’s writings. What makes their work stand out even more, though, is how the animators still manage to blend time-tested Western storybook imagery with Japanese touches. Whether it’s the presence of sweeping panoramic shots, speed lines amidst otherwise bloodless action scenes, or the wide, expressive eyes on many of the characters, keen-eyed fans may be pleasantly surprised to find the anime handiwork lurking beneath the surface.

In terms of audio, the movie manages to be both a product of its day and surpasses those expectations. At a time when “direct-to-video” in America was generally looked down upon, Rankin/Bass pulled no stops in attracting some of the best thespians and voice actors in Hollywood. Be it game show mainstay Orson Bean as Bilbo, Smaug having the gravelly voice of Richard Boone, or comedian Brother Theodore’s stint as Gollum, their performances lend an added emotional weight to the characters. Meanwhile, the musical numbers, composed by Jules Bass and Maury Laws, incorporate the songs and lyrics Tolkien himself wrote down into a fascinating, if somewhat cheesy, repertoire. It would be the opening song, however, “The Greatest Adventure“, by Glenn Yarbrough, that’s arguably the most timeless and haunting of all.

There And Back Again

The New York Times lavished praise on The Hobbit, calling it “curiously eclectic, but filled with nicely effective moments.” The film’s teleplay by Romeo Muller won a Peabody Award in 1978, while the movie itself got nominated for the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation, only losing to the original Star Wars. Not everyone was pleased at the time, however, whether it was the Japanese-made animation, with Tolkien scholar Douglas A. Anderson calling it “execrable”, or criticism over making the adaptation more child-friendly, among others.

Though the film never saw a theatrical release, it would eventually find a decent enough afterlife through Betamax, VHS, and eventually DVD re-releases over subsequent years. Yet while it has since been overshadowed by adaptations much more successful than Rankin/Bass ever imagined, it would nonetheless leave a lasting legacy, especially for the Japanese animators involved.

In more recent years, the movie has seen a reappraisal for how much it stays true to Tolkien’s work, even by the standards of its time. (Source: YouTube)

Not only did The Hobbit serve as a gateway to Japanese anime much like the original Speed Racer (1967-68), but it opened new doors for Topcraft. Further collaborations with Rankin/Bass followed, including an animated adaptation of Return of the King (1980) and the well-received The Last Unicorn (1982). The experience Hara and much of his staff accrued, as well as the international accolades, paid off with the release of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). Under Hayao Miyazaki’s leadership, they were subsequently reforged into Studio Ghibli. And the rest, is history.

As quaint as the film may seem now, its legacy could not be understated. With a new anime series, The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim, set for a 2024 release, what better time than now to see those small steps to greatness?