The story of South Korea’s animation scene, and its connections to Japanese anime, is one that goes back decades. As early as the 1980s, it wasn’t unheard of for Japanese companies to outsource work to Korean studios, which used the experience to foster their own homegrown industry. Space Thunder Kids (1991), however, isn’t one of their finest moments. If anything, it’s a bizarre snapshot of that history that offers a glimpse into an era that could have all too easily been forgotten.

“Directed” by Elton Reins and released by ADDA Audio Visual Limited, in actuality, it’s a production of Joseph Lai’s IFD Films & Arts Ltd., which in time would spawn Beauty and Warrior (2000) from Indonesia. Even if you’re somewhat familiar with the Hong Kong-based schlockmeister’s portfolio, which includes Godfrey Ho’s similarly infamous ninja movies, the 70 minute-long romp can be enough to make you wonder just what was he thinking. Or for that matter, what the circumstances were behind this movie’s creation.

The trailer for Space Thunder Kids is rife with half-enthusiastic, yet vague taglines and failed attempts at bombastic spectacle, which only give a taste of what you’re about to experience. (Source: YouTube)

Yet as atrocious as the resulting film is, it’s not without some historical merit or value, however hard it might be to believe at first glance.

A Less Glamorous Time

Space Thunder Kids’ plot, as described on the back of its VHS and DVD covers, seems straightforward enough. A Dark Empire is determined to conquer the universe and anyone who gets in its way. The titular heroes, three valiant youths patrolling the cosmos, join forces with Earth’s Guardian Army and rise up to challenge the forces of evil.

In practice, that’s more of a broad-strokes guideline, as the actual story manages to make an already generic premise hard to follow. Apart from a general sci-fi theme and the villain being an evil emperor, there’s very little in the way of consistency, as a space battle could jarringly shift to a poorly choreographed super robot fight. Pacing is practically nonexistent, as the movie fluctuates between overly dragged-out filler scenes (such as looping explosions) and sudden transitions that leave more than a few plot points hanging. Indeed, it’s not even clear who the titular kids are supposed to be, when separate teenage teams are shown that have no real connection to one another.

If you think that it’s as though the producers carelessly spliced in several shows into one, it’s because it’s not far from the truth. In classic Godfrey Ho and Joseph Lai fashion, the movie is a strung-up hodgepodge of eight Korean sci-fi animated works released throughout the ‘80s. Among those that have been identified over the years include Computer haekjeonham pokpa daejakjeon/Savior of the Earth (1983), Super Teukgeup Mazinger 7 (1983), Bulsajo roboteu Pinikseu-King (1984), and Micro Teukgongdae Diatron 5 (1985), many of which have also been dubbed and distributed separately under Lai’s watch. Strange as this may seem, this is where Space Thunder Kids truly “excels”, if it be could be called that.

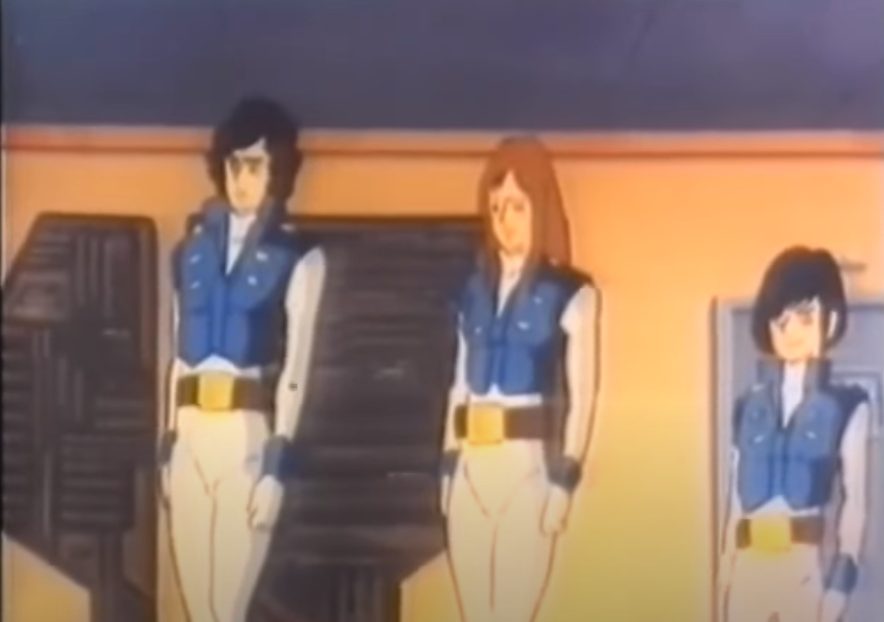

Even in mangled form, a valuable snapshot of South Korea’s animation history is presented, captured from when the country had begun moving away from a decades-long dictatorship. As it becomes very evident through various spliced clips, you get the impression that the nation’s people then (and in a sense, now) had a fascination for anime strong enough to spur the local industry to make their own, with some using the experience gained from doing outsourcing work for Japanese studios. The results from this time, however, aren’t exactly flattering. With character designs that look like blatant ripoffs of popular shows like Gundam and Macross, mecha resembling a hodgepodge of ‘70s Super Robots, and subpar visual quality, they come off as cheap imitations rather than being inspired.

Nonetheless, as ignoble as this all seems, if not for such birth-pains, Korean manhua and animation as they exist now wouldn’t have made the strides they made. Indeed, it’s that historical significance, and how it’s available elsewhere across the globe to fans who may otherwise never have known about it, that almost redeems this strange production.

Almost, but not quite.

A Comedy of Errors

Even when put in isolation, Space Thunder Kids is just plain bizarre. On top of the nonsensical story, there’s barely any effort to make the already subpar visuals consistent or enticing. Be it ships flying backwards, overly long padding sequences, or the general wonkiness of the animation itself, it could, at best, be described as “so bad it’s good” or “a comedy of errors.”

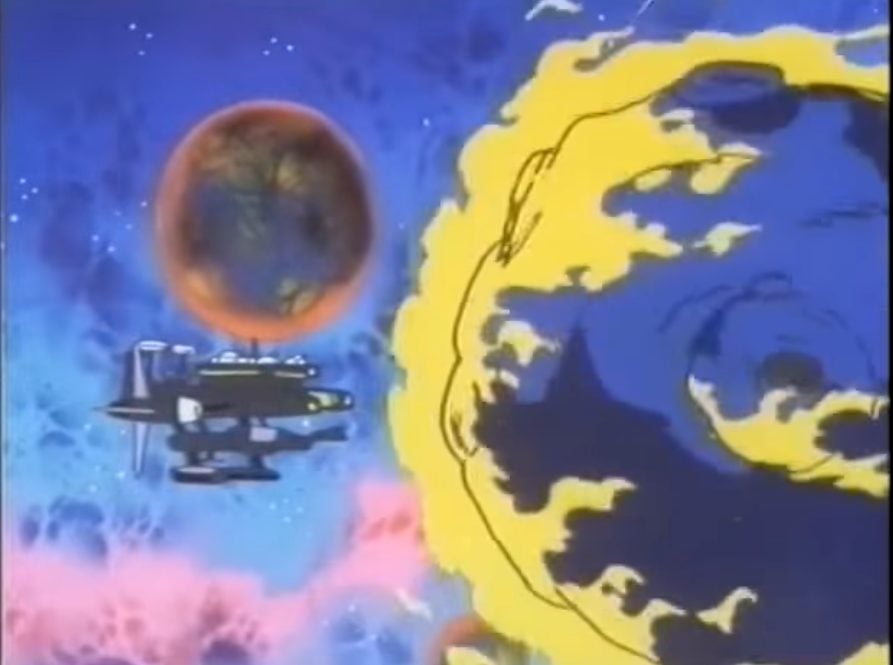

One of the many drawn-out padding sequences of the movie, which highlight both the subpar, looping visuals and bad voice-acting. All of which contribute to such scenes feeling much longer than their actual runtime may suggest. (Source: YouTube)

This extends to the audio, which seems as though it was recorded on tinny equipment. The English dubbing, for instance, could be described as amateurish and done by a skeletal cast. You could tell at times when the same person was trying to speak for multiple characters, with little real change in tone. Even when there’s more than one actor performing, it’s not much of an improvement, as it comes across as though they’re poorly improvising the script. Coupled with a soundtrack that seems ripped out from other films and anime, it can be laughable and cringe-inducing, depending on how sober you may be by the time it ends.

The movie has gone down in online infamy as the subject of many reviews and parodies, even being spotlighted by legendary YouTube Poop creator WalrusGuy. Circa 2009. (Source: YouTube)

It is perhaps unsurprising why Space Thunder Kids was left to languish in bargain-bin obscurity almost immediately after it was finished. Coincidentally, it also comes as little wonder, then, why it became something of a meme upon being discovered online in the 2000s. More than a few YouTubers and commentators went on to riff on this bizarre piece of Korean cinema not long after, further cementing its infamy. Thus, though the heyday of its exposure may have long passed, the strangeness of it all ensures that it will never be entirely forgotten.

Which may well be for the best, even if only for a curious glimpse into one chapter of South Korean history.