Master of Martial Hearts (2008-09). Or, How Not to Subvert Expectations

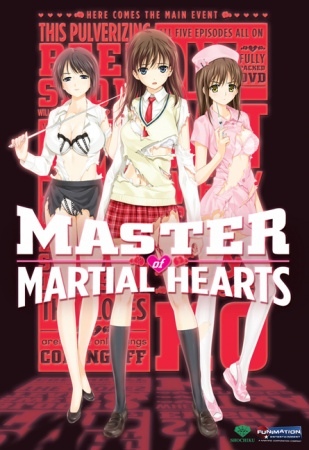

The 2000s were a peculiar time. In addition to being an era when Japanese nerddom had gained wider recognition and acceptance, this was also when the so-called “Panty Fighter“ subgenre became one of the more popular (and infamous) ones in the market. Enter Master of Martial Hearts (Zettai shôgeki: Puratonikku hâto – Hashiridasu shukumei; 2008-09), an OVA that at first glance, could have easily been forgotten amidst the competition. That is, if not for its shoddy production and demonstrating how not to “subvert expectations.”

With a total runtime of over two hours (broken up into five episodes) and directed by Yoshitaka Fujimoto, this comes from Arms Corporation, the same folks behind the likes of La Blue Girl (1992-93), Elfen Lied (2004) and the later Ikki Tousen entries (after 2007). Despite showcasing the same “trademark” sexuality associated with the studio however, the anime comes across as weirdly out of place. Although, as you’d soon discover, this works more to its detriment than anything else.

Hearts and (Lack of) Minds

The OVA’s deceptively upbeat opening gives a taste of its bad animation quality and soundtrack. Circa 2011. (Source: YouTube)

Master of Martial Hearts follows schoolgirl Aya Iseshima (Kaori Nazuka, Trina Nishimura), who, along with her best friend, Natsume Honma (Satomi Akesaka, Cherami Leigh), stumbles upon a battle between a shrine maiden named Miko Kazuki (Ai Nonoka, Alexis Tipton) and a flight attendant. After intervening in the fight, Aya learns of a secret tournament, wherein the victor gains a gem called the Martial/Platonic Heart, which could grant any wish. Upon learning that her new friend had vanished without a trace, however, she joins to win the prize and learn the truth. Things go downhill from here on.

That’s as close to you’ll get to a coherent plot, however. A good chunk of the runtime, indeed, comes across as rather generic. The quest for answers comes off more as either filler or an excuse to dump her into various contrived situations, whether it’s a poolside or the middle of an idol event. Each bout leaves more questions than answers. Not that you’d have much reason to feel sympathetic for the heroine and anyone else for that matter, as the characters themselves tend to be unlikable caricatures (with Aya alternating between being bland and homicidal) or otherwise unmemorable. Compared to contemporaries like Ikki Tousen, there aren’t even any underlying cultural references like the Romance of the Three Kingdoms to lend some flair.

The battle sequences themselves, and the general setup, aren’t exactly much to write home about, either. Apart from some handwaves about secrecy and desiring the prize, there’s no real rhyme or reason behind the tournament. It’s never really explained, either, why most of the combatants are glorified cosplayers, with faux-kung fu skills and gimmicky moves vaguely based on who they’re supposed to be. Apart from teacher Izumi Hayakawa (Hirata Hiromi, Wendy Powell), none of the rivals really have any clear connection other than people that the heroine has to beat up. No amount of clothes ripping off inexplicably or gratuitous nudity (of which there’s quite a bit of both) can really cover up just how dull and stupid they could get.

Not that the overall audio-visual execution makes up for that. On average, the animation quality’s janky and sub-par, with errors (like off-angle faces and tacked-on special effects) and at times low-effort art on display. Even at its best, particularly during the battles, you’d find the supposedly high-octane action to be more like unchoreographed cat-fights than anything else. This also has the effect of making the fanservice seem even more superfluous and distracting, than titillating. The sounds, meanwhile, come off cheap and grating, with the English dub (done by FUNimation) seeming half-baked at best. The one high point would be the original Japanese track, though only in the sense that it’s decent, and little else.

The battle between Aya and her teacher, Izumi, demonstrates just how stupid and stilted the “martial” fighting can get. Circa 2011. (Source: YouTube)

A Moralistic Failure

Master of Martial Hearts, by those fumbles alone, would have made for a bad anime. At the very least, it could be the kind of bland fodder doomed to be forgotten in some bargain bin at Mandarake. But then, there’s the final episode in its entirety.

Without spoiling too much, it’s revealed that not only are the foes defeated over the course of the story suffering a fate worse than death. More than that, the whole Martial/Platonic Heart affair’s shown to be one convoluted revenge scheme by Aya’s own friends against her, for the sins of her mother. By that point, the true conceit is laid bare. The OVA’s shown to be an attempt to satirize and ultimately rebuke panty fighters, whether for being fundamentally sexist or cruel to everyone involved.

It hits as hard as any of the blows seen up until then, “subverting expectations” years before that term became an infamous meme. But you’d be hard-pressed to call it a “success,” however. Barring a few scenes beforehand (like the idol event and how it lingers a bit on the otaku audience), it comes out of nowhere. The in-universe explanations fail to convey that weight, either, be it blaming the heroine for things the villains did, the plot hole-laden reveals about her family’s past and the tournament, or the schemes-upon-schemes (which would never fly in reality) that inexplicably come up. While the shift in tone afterward, which turns the anime into a dark, sloppy take of the Liam Neeson action film Taken (complete with guns and references to sex trafficking), is so jarring that it completely breaks any suspension of disbelief you may still have.

This isn’t even getting to how this, ultimately, makes the OVA little more than a moralistic exercise in spite, albeit one that’s not even sure of what it wants to be. The copious nudity and fanservice mentioned previously would not at all appeal of the kind of viewers who either dislike or are neutral to panty fighters, to begin with. The in-your-face smearing of otaku as ugly, misogynistic pigs (especially evident in the idol event), and by extension the actual audience for liking such works come across as mean-spirited, if not outright insulting. Combined with an unlikable cast and a story that undermines its own message, you end up with a nihilistic mess that pleases no one.

Barring a three-volume Seinen manga adaptation (2008-10) and a relative handful of attempts at making merchandise, Masters of Martial Hearts came and went, superseded by Arms Corporation’s other projects. Yet to this day, it holds a degree of notoriety. Whether as bile fascination, or the subject of scathing reviews online by various commentators, it remains a clear example of how not to do a subversive “deconstruction” of anime.