When we think of all the ways the world has changed, it’s easy to focus on the really big recent changes, like smartphones and ubiquitous Internet everywhere. But even things we take for granted today, like USB or laser printers or computer networks, have represented huge innovations in the daily technological lives of human beings. I thought I’d write a post on technology has changed in Japan over the past 29 years, and explore Japanese works on computers and related devices.

Japan in the Early 1990s

I came to Japan in 1991. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was arriving at the exact moment Japan’s huge asset bubble — during which all the land in Tokyo was worth more than all the land in the U.S. on paper — was bursting. The process was slow to unfold, and at first Japan seemed very “bubbly” (a word the Japanese use now to describe the exuberant economy back then), but slowly business failures skyrocketed as land prices and the NIKKEI average got cut in half. Japan has only recently started to emerge from its two “lost decades” as inflation and land prices finally began to tick up.

Want to see what Japan looked like back then? Here’s a video!

Writing a post about how computers have changed in 25 years, specifically the presumably simple act of typing Japanese on a Mac or PC.

This is what Japan was like when I got here in 1991. Note the guy on the giant cell phone about 1 minute in.

via https://t.co/MGtyBbJFtm pic.twitter.com/WNDoD3m6wQ

— Peter Payne (@JListPeter) June 6, 2020

(Just think, 29 years from now, the current fashions and technology we take for granted today will look this bizarre to us. I hope I’m around to re-read this post!)

1991 was a heady time for me. I had just started my career as an ESL teacher, working at a small English school then moving to a larger trade school where students got a 2-year education in English, and took additional courses focusing on hospitality or flight attendant-related fields. I was studying Japanese, preparing for the upcoming Japan Language Proficiency Test, and learning about my new country. I was also visiting the anime and CD shops in my city that would eventually cause me to start posting a daily text list of stuff I’d acquired for purchase to Usenet’s rec.arts.anime board, which I called The Japan List. Of course this eventually become J-List.

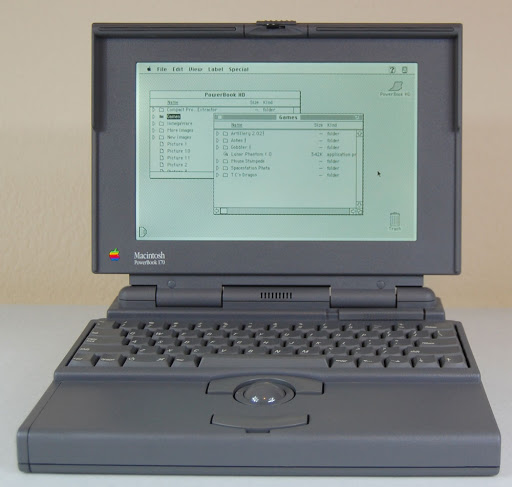

1991 was also for another reason: the beginning of some really awesome computers, especially the first laptops that was actually worth using. I got the Powerbook 170 when it came out, despite the US$4,599 cost (equivalent to $8,633 today), and had lots of fun forming a computer club with gaijin and Japanese friends, exchanging computing tips and generally geeking out about technology together.

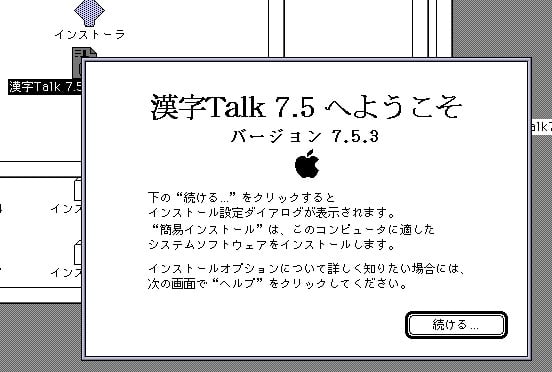

I remember one frustration, though. While System 7, the big redesign that changed pretty much every aspect of the Mac up to that point, had come out in English, there was no way to enter Japanese text. I remember some hack that allowed users to get Japanese input to work in English System 7 by copying over certain files from System 6.x, but it was a lot of work. I can’t for the life of me imagine how we passed knowledge about thise hack from user to user without the Internet to make it possible.

Eventually KanjiTalk (as the Japanese port of Mac’s OS was known) finally came out.

TrueType Fonts in Japanese

One of the major achievements of modern computers was the creation of the Postscript computing language, which enabled laser printers to print characters that were defined mathematically, so they could be printed beautifully at any resolution. The reason Mac succeeded as a platform was because Postscript coupled with the breakthrough Laserwriter laser printer, which cost “only” $6995 in 1985, allowed the platform to dominate the new desktop publishing field.

But Adobe extracted hefty licensing fees for Postscript, which hobbled the industry for years. In response, Apple developed TrueType fonts, which it licensed to Microsoft, to create an alternate standard that could be used freely. When TrueType fonts finally arrived in kanji, it was truly an achievement. (In addition to loving technology, I’m a bit of a font-and-typography geek.)

The Growth of Technology in Japan

We often think of Japan has a technological powerhouse, but in a lot of ways, the opposite is true. While Japan did get the first color computers, resulting in awesome developments like the dating-sims and visual novels we have today, and some important tech ideas like the first cell-phone camera were invented here, Japan largely moves at a slow pace technologically.

My wife and mother-in-law were recently forced to upgrade their 2006-era cell phones because the 3G standard is being closed down, and I had to upgrade both of their ancient PCs because service for Windows 7 has finally ended. Many of the distributors and other companies J-List deals with are highly resistant to change, which is not always good for their businesses.

How Japanese Works on Computers

In case you’re curious about how Japanese works on computers, I’ll explain. All modern computing devices let you set active “keyboards” and switch between them, depending on what language you’re entering. While there are 26 letters in the English language, there are thousands upon thousands of kana and kanji characters. So how do you tell the computer what you want?

The answer is a front-end processor that has a dictionary of words, and shows you suggestions on-screen. If you type にほんご into a document, the system converts it into 日本語 for you. The equivalent of a “typo” in Japanese is when you don’t pay attention to the suggestions the device gives you and select the wrong one, like a man who suggested to his girlfriend that they live together (住もう) but accidentally texted “sumo wrestling” (相撲).

If you’re wondering at the katakana characters on the keyboard in the gif above, they’re a remnant of the old kana layout system that was in use in Japan back in the 80s. It’s totally not needed anymore, since you can type romaji (Romanized Japanese) into the computer, but you still see the characters on Japanese keyboards sometimes. My wife, who had the bad luck to learn the old kana typing layout back in high school, still has trouble typing some words with the normal QWERTY layout.

Today Japanese users just use IME on Windows and Kotoeri (though they stopped using that name) on Macs, and probably don’t think twice about it, but historically Japanese computer users have taken their kanji input methods quite seriously, arguing over whether EGBridge or ATOK8 or Google IME offered the smoothest input with the least errors. As with any dictionary system, all front-end processors allow you to register new words. When the name of the new imperial era of Reiwa was announced, every Japanese in the country dutifully registered the new kanji 令和 in their cellphones and computers.

Computers Killed the Kanji Star

Computers, cell phones and tablets are all great to use and have allowed us to do faster and better work than we could have ever conceived of. They also robbed the entire nation of Japan of the ability to write their own language properly.

It turns out that entering kana characters into a device and hitting the space bar a few times until the kanji you need comes up is a pretty convenient, and your brain quickly realizes it doesn’t need to maintain the synapses that had been set up when you learned manual kanji writing, in the same process that caused you to forget those two years of Spanish you took back in high school. Now there’s a common pattern of Japanese people being able to write kanji properly while they’re in school, but quickly forgetting how to write more obscure characters the minute they enter work life. Reading is maintained with no problems, but without constant practice, the ability to write kanji declines quickly.

The same thing happened to me: there was a time when I could write almost all of the 2,136 jōyō kanji, but thanks to our convenient modern era, I forgot how to write most of them. It’s why I recommend that students of Japanese come up with strategies to learn to read kanji characters, including writing characters or sentences repeatedly to aid memorization but avoid stressing out about maintaining kanji writing ability, because it’s pretty much impossible.

Thanks for reading this article about how Japanese works on computers. Did you learn anything new? By the way, we’ve got a post about classic technology seen through anime if you want to check it out!

If you’ve got any topics you’d like us to write about, feel free to tell us in the comments below, or on Twitter!