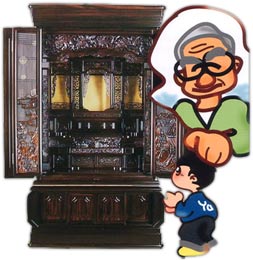

There are many things that American houses have which their Japanese counterparts lack, and vice-versa. A Japanese home will generally have a recessed area by the front door for people to leave their shoes, hardwood floors with unusually steep stairs, and at least one washitsu or “Japanese room” with traditional tatami mats and paper doors and other cool things like that. Homes in America are different, with big ovens for baking (very rare in Japan), a garbage disposal for getting rid of uneaten food (not allowed here because rice would gum up the pipes), and central heating (unthinkable in this country where rooms are heated one at a time). Another thing you’ll find in Japanese homes but not in most American ones is a butsudan (boo-tsoo-dahn), or Buddhist Altar, the centerpiece of Japanese family life, and afterlife, if you will. Every morning, my mother-in-law takes the first bowl of rice out of the rice cooker and offers it at the altar along with three sticks of incense, so so her mother and father know they’re not forgotten. Strictly speaking, only the head of a household will have one of these altars; other family members such as children who have moved out will return to their “base home” to participate in family events at various times during the year, which binds the family together in ways that are difficult for Westerners to comprehend. To my unfamiliar eyes, the Buddhist altar in my house is very similar to the Ark of the Covenant from Raiders of the Lost Ark, a radio for talking with one’s dead ancestors.

While Buddhist icons like temples or home altars focus attention on those who have gone on ahead, the other side of Japanese religious imagery is Shinto, which celebrates kami or spirits in natural objects like a mountain or a stream. While the austere imagery of Buddhism provides comfort during times of sadness such as funerals, Shinto ceremonies are happy and life-affirming: weddings, naming a new baby, breaking ground on a house to be built, praying for good luck on the New Year or carrying a mikoshi, a kind of portable shrine, around at the summer festivals. For cultural reasons that I can’t quite understand, it’s much more common for those of us who became interested in Japan through its popular culture to be more familiar with Shinto imagery than Buddhist. Whether you’re talking about the manga stories of Rumiko Takahashi or watching the many anime characters who wear the now-famous garb of a Miko-san (Shrine Maiden), it’s far more common for the themes found in Shinto to find their way to the minds of outsiders like us than Buddhist imagery. I wonder why that is?

A Buddhist Altar is a radio for talking with one’s ancestors; some otaku have fun carrying a mikoshi in Akiba.