When I was in the U.S. I played with Apple’s new iPhone in an Apple Store and immediately knew I had to have one. (It’s funny how my business trips to the U.S. just happen to coincide with Star Wars movie releases, major U.S. product launches, and so on — please don’t tell my wife.) The iPhone is great, and even in Japan, where its phone functions don’t work, it’s quite useful as a WiFi device that allows me to do my mail, check websites, and enjoy music and videos. One of the big benefits of Apple’s OS X operating system is that there’s only one worldwide version, with everything international users need included on the install DVD — this is a huge improvement over the days when the Japanese version of the latest OS would take a year to show up. While the iPhone does support many non-English languages, including the ability to display (but not input) Japanese and Chinese, it seems to me that Apple will have some challenges making the device work for users around the world.

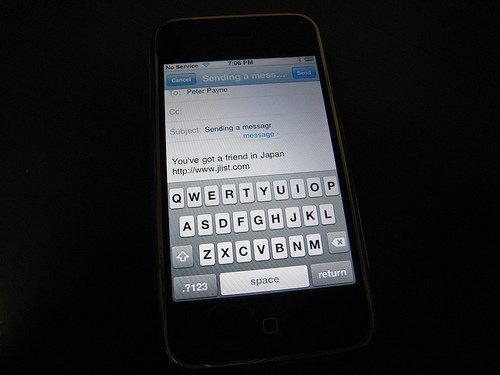

I remember a trip I made to a MacWorld Expo back in the 1990s. Apple was working on a Japanese version of the venerable Newton, and asked me if I’d write some kanji characters with the software they were testing. If you’ve ever thought that the Newton was hard to use with the standard Roman alphabet, it was even more difficult getting it to recognize my handwriting in Japanese, and the device was eventually “Steved” (cancelled, to use the terminology of the day) not too long after. Happily, the iPhone has an on-screen keyboard for you to type on, which works in tandem with an internal dictionary that corrects errors you make while typing, and it learns too, so that it eventually stops trying to tell me that my website is “joist.com.” Getting this dictionary just right for users in other countries will be extremely important for Apple, since no one would want their phone suggesting incorrect spellings to them as they type. Inputting complex languages like Japanese will be a bit more difficult, and it will call for a “front end” input manager as seen in the built-in Kotoeri for Mac and Japanese IME for Windows. The way it works is, you select Japanese as the current input method, then type a word like “nihongo” and press the space bar. The front end program then guesses what kanji it thinks you want, and you keep typing or choose another character if it guessed wrong. This is usually fairly straightforward, but there are some words that have many possible kanji, like kousei (koh-SEI) which could mean structure (構成), justice (公正), public health (厚生), or fixed star (恒星), depending on which characters you choose. One issue that might miff would-be iPhone buyers in Japan is, there are several front-end kanji input programs on the market, like EGBridge and ATOK, which offer more accurate guesses about what kanji you want to enter. If Apple requires Japanese users to use, say, the default Kotoeri input method, some of them will pass on the phone for that reason alone.

Back when I was single, I did a fair bit of traveling around Japan, including hitchhiking, which wasn’t always easy since the Japanese don’t have a custom of giving rides to strangers at all (let alone big hairy barbarian gaijin). I had my best success by dressing nicely and putting on a tie then going to the freeway I.C. (“interchange,” i.e. the on-ramp) and standing with a clearly written sign featuring where I wanted to go. I also brought some kind of gift for people who gave me a ride, like cigarettes from the U.S., since gift giving really oils those squeaky wheels here. Once I was trapped at a truck stop at midnight in cold part of northern Japan, and a man appeared offering to let me come stay at his house for the night. Normally I wouldn’t consider going off with a stranger, but one of the really good things about Japan is how helpful people are to okyakusan (visitors, guests), and the man was just happy to be able to show a foreigner some hospitality. I’ve always like enka, the sad traditional music of Japan that’s roughly equivalent to American country music and which got its start from fishermen trawling the lonely seas. Just as the “soul” of country music is more or less based on Nashville, Tennessee, the eerie sounds of enka eminate from northern Japan, especially chilly Aomori Prefecture, at the top of the main Japanese island. I have fond memories of hitchhiking all around that lonely part of Japan, smelling the salty air of the Straits of Tsugaru, which bridge Honshu and Hokkaido and of which many enka songs are sung. Ah, those days were a lot of fun…