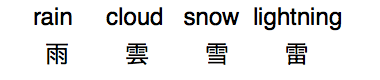

Part of learning to read and write kanji involves learning about the building blocks (called radicals) that make up the characters. Although they can look like so much goobldygook when you’re not used to them, most characters are built with parts of other characters which help guide their meaning. For example, characters for things like language, to read, to translate, and to speak all contain the same left half (called gomben), which is the character for “to say.” Kanji characters are often tied to the elements, and there are radicals for characters related to water (found in characters for sea, fish, tide), fire (found in ash, smoke and to burn), or rain (which shows up in characters for cloud, snow, and lightning) — all quite logical, really. When you study kanji for far too long, as I have, you start to imagine you can see the threads of thought that went into their creation. For example, the kanji for “second” (as a unit of time) has the same right portion as the character for “sand” and I imagine some scholars in ancient China millennia ago working out why it was logical for the two concepts to be linked in this way, because of the way time can be measured with an hourglass.