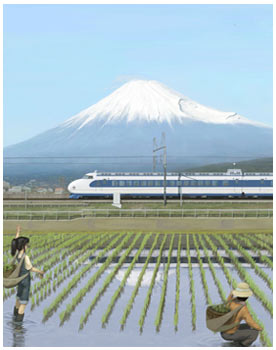

One impression of the Japanese language I got soon after arriving here was one of “duality,” and it seemed that most of the new concepts I was encountering had “two faces” to them. Often ideas we cover with one word in English are split into two in Japanese, like oneesan and imouto for “older sister” and “younger sister,” which takes some getting used to since we just say “sister” without considering relative ages. The Japanese have two words to express “cold,” samui (sa-moo-ee) meaning coldness in the air and tsumetai (tsuoo-meh-tai) for something that’s cold to the touch, and the idea of food being “good” (oishii) is completely separate from a product being of good quality (which is ii, pronounced like the letter “e”). The Japanese often import English words then split them into two versions for their own convenience: glass in a window is garasu, while a glass you drink from is gurasu, and you can be sure gaijin will get the wrong word every time. Another source of confusion comes from the fact that each kanji has two readings, a Chinese and a Japanese one. A good example of this is the kanji for “mountain,” which is san using the Chinese pronunciation or yama using the Japanese one, and for most every mountain these can be used interchangeably, e.g. either Akagi-san or Akagi-yama is acceptible when referring nearby Mt. Akagi. One exception is Mt. Fuji, which should always be pronounced “Fuji-san” in Japanese, as the name Fuji-yama has become hopelessly cliched after decades overuse by American soldiers and foreign tourists.

Mt. Fuji should always be Fuji-san, never Fuji-yama. And please don’t say “saki” either.