I’ve learned a lot about the Japanese people in the 28+ years I’ve lived in Japan. They’re extremely hardworking, which is one reason I enjoy working alongside the Japanese staff of J-List. They’re hygienic by nature, already having a tradition of wearing protective masks and washing hands regularly, which has been very helpful during the virus crisis. I also learned that Japanese can be extremely superstitious, holding many unique and colorful beliefs. So here’s a post with 12 Japanese superstitions explained, with cute anime images!

Japanese Superstitions: Blood Types

One thing we learn early as fans is that anime and manga creators can be obsessive about blood types, meticulously assigning them to their characters. The origin of the belief that blood type and personality traits are related comes from research done in Japan in the 1920s. While rejected by the medical community, blood type superstition remains strong in Japan and South Korea today.

The supposed blood type personality elements are

- Type A people are extremely organized and meticulous, almost to the point of being anal retentive.

- Type B are creative but sloppy and are “my pace” (living life at their own pace). I am type B, and my type-A wife constantly writes off the things I do that annoy her to my blood type. There are laws in place to keep employers from discriminating against workers by blood type (primarily type B people), and it’s illegal to ask blood type on job applications.

- Type O people are easygoing and make natural leaders. During WWII the Japanese military promoted men with type O blood over other blood types, believing them to be better leaders.

- Type AB are talented and composed, but can be “two-faced,” having dual natures they hide from others.

The Japanese Are Very Connected To Their Ancestors

While most Japanese will insist they have no religion at all, the “default” spiritual system of Japan is Buddhism, and as a rule, the Japanese generally feel a close connection to their ancestors, specifically their deceased grandmother and grandfather. In situations where a Christian would feel they’d received internal guidance from Jesus or Mary, I’ve observed that the Japanese will believe their dead grandmother (or whoever they were closest to) was present, showing them what to do. One of the most important holidays in Japan is Obon, a Buddhist event when the souls of the dead are believed to return home for a visit, riding on horses and cows (represented by cucumbers and eggplants, which parents make with their children).

Don’t Stand Chopsticks Up in Rice

Many Japanese beliefs are related to funerals. Don’t stick chopsticks straight up in rice, because it’s done for the dead at funerals, and don’t hand food to someone chopstick-to-chopstick for the same reason. Similarly, you should never sleep with your head pointing north, because this is reserved for the dead on their final night before cremation. And make sure to throw salt on your body when arriving home after a funeral, or the soul of the dead person will enter your house. You wouldn’t want that!

(Salt has always been seen as a purifying agent in Japan, and whenever someone my wife dislikes comes to our house, my wife will actually throw salt on the ground to purify it after the person has left. Try it with people you dislike, it feels oddly reassuring.)

The Number 4

There are a lot of number-related superstitions in Japan, the most famous being the number 4, which can be read shi, which phonetically means 死 (death). They also dislike the numbers 13 (the traditional unlucky number from the West) and 9 (which can be read ku (苦, meaning “agony”). Airline counters will usually omit all three of these numbers. On the other hand, Friday the 13th is oddly seen as a day good things happen in Japan.

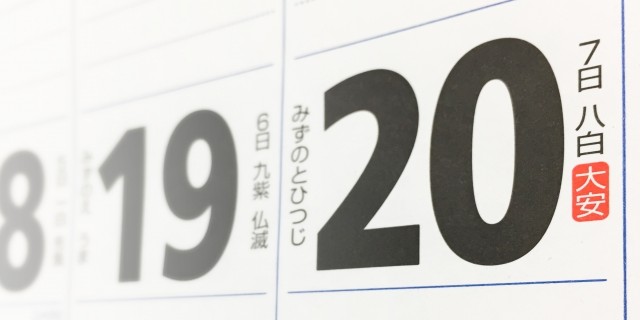

Japanese Superstitions: Lucky and Unlucky Days

If you’ve ever bought a Japanese calendar from J-List, you might have wondered what the kanji are written on the days were. They are rokuyo, a system of six rotating days that including taian (“big peace”), the luckiest day for getting married, butsumetsu (“death of Buddha”), the unluckiest day, and tomobiki (“take you away with him”), a day you should never have a funeral or the living will be “taken away with” the deceased person. Generally Japanese people will not take delivery on a new car before checking their calendar to choose a “lucky day” for the arrival to take place.

Don’t Write Names in Red

You should never write a name with a red pen. It’s basically instant Death Note if you do.

Names and Superstitions

The Japanese can feel strongly about names, and the luck they bring. When I first arrived in Japan I did a stupid thing, legally registering my name in kanji, as 飛偉多阿・平院, because I thought it looked cool. The downside is that I have to write these difficult characters on every official form I fill out. I’d like to change my name, but my wife insists that doing so would be a terrible mistake, fundamentally altering my destiny, so I’ll keep it the same.

The Red String of Fate

Many Japanese beliefs come from China, like the belief that someone is connected to the person they’ll eventually marry by a “red string of fate” (運命の赤い糸).

Sneezing

If you sneeze, it means someone is gossiping about you. Have you noticed this in anime?

Every Western Superstition

In addition to various and sundry local folk beliefs, the Japanese have imported many of the superstitions believed in the West, from the number 13 to nervousness about black cats and walking under ladders. The Japanese positively love Western astrology, too.

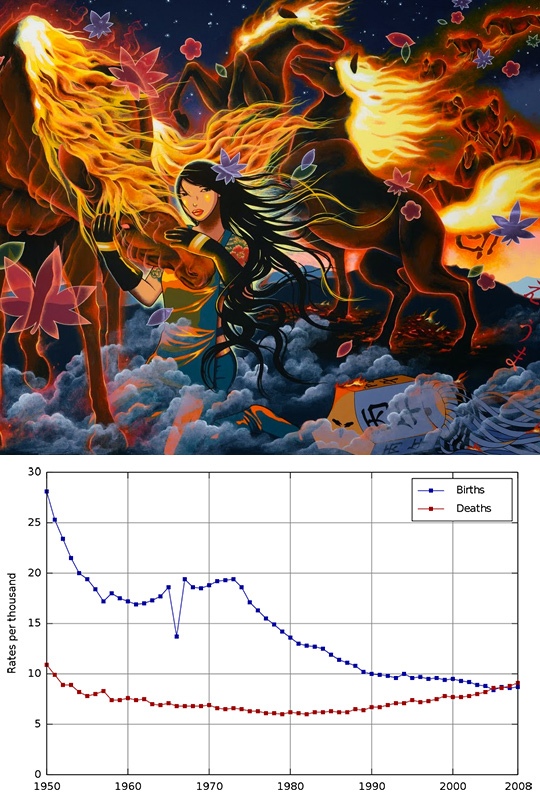

Hinoeuma: Fire-Horse Girls

The Chinese Zodiac a big part of life in Japan, and it’s believed that the animal of the year you were born in affects your life. The “worst” year to be born in is called 丙午 hinoeuma, or “fire-horse,” a remnant of a romantic story about a woman named Oshichi who met a temple page during a fire in Edo in 1682. She wanted to see the boy again, so she got the bright idea of setting the city on fire a second time, so they could be together. This grew into a superstition that girls born on the 6th cycle of the Year of the Horse would be headstrong and unable to be happy in life, which caused Japan’s birthrate to drop notably the last time it happened in 1966. There’s another Fire-Horse year coming up in 2026…I wonder what will happen?

The Biggest Japanese Superstition: Yakudoshi

Finally, the most closely followed of the Japanese superstitions is yakudoshi, or a “bad luck year” when everything will go wrong, which means you should always avoid doing things like buying cars, building houses, or starting a new business around these periods. The ages are 25, 42, and 61 for men, and 19, 33, and 37 for women. Happily, you can go to certain Buddhist temples that specialize in yaku-yoke, the removal of yakudoshi bad luck. Like most aspects of Japan, this belief is very old, dating back to the Kamakura Period (1185–1333).

Got any more questions on Japanese superstitions? Ask below and we’ll reply!

J-List’s sister company J18 has been hard at work on new projects, and the first one we have to announce is Training Day, a newly licensed doujinshi that’s 100% uncensored, and fully translated to English. Preorder the new books now — it will ship out to everyone in June 2020!