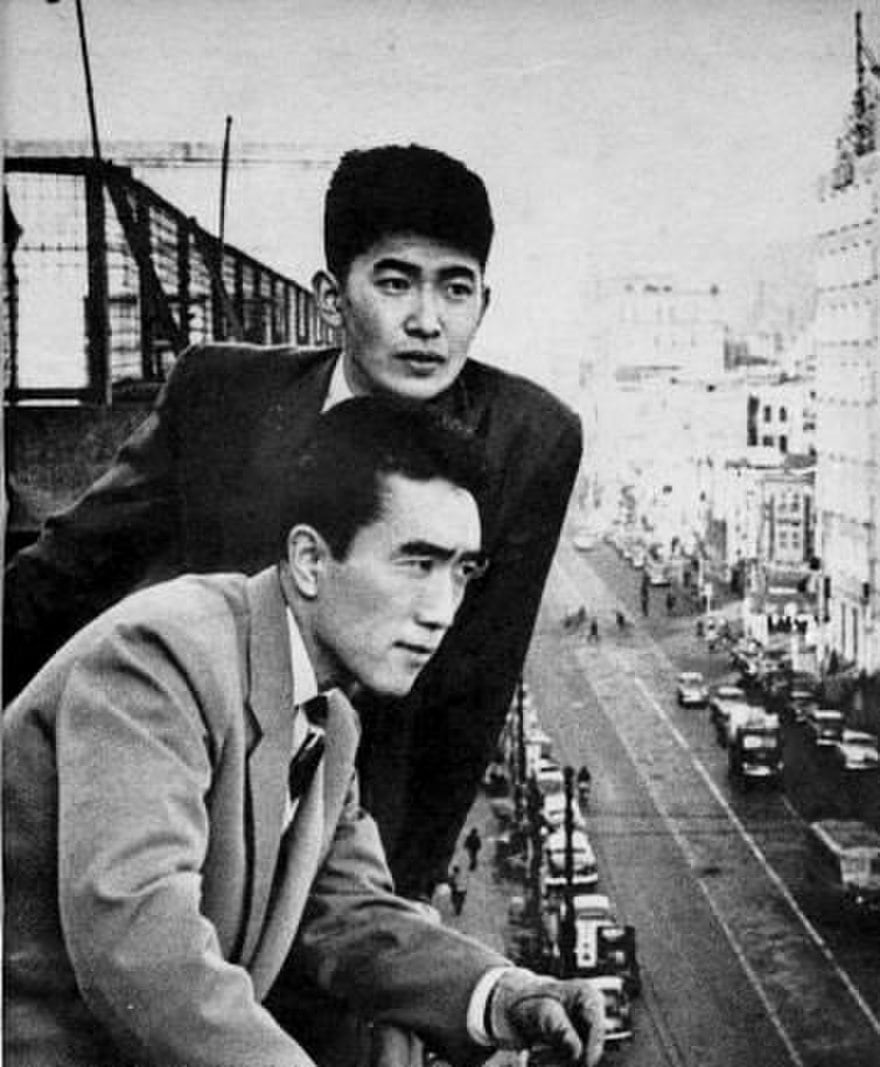

After a protracted struggle with pancreatic cancer, former Tokyo governor Shintaro Ishihara passed away on February 1st, 2022, at the age of 89. To say that the novelist-turned-politician had courted controversy over the years would be an understatement. His legacy, however, goes beyond books, a career as a firebrand, and diplomatic stunts. He’s also infamous for pushing Bill 156, also known as the “Tokyo Metropolitan Ordinance Regarding the Healthy Development of Youths”, which raised the ire of otaku in Japan and abroad for years.

To understand that notoriety, you need to go back over a decade. Although UNICEF’s appeal in 2008 for the banning of what it called “child pornography in manga comics, animated films, and computer games, as well as individual possession” wasn’t seriously acted upon at first, Ishihara was notably vocal about not just conflating such sexualization within anime, but also for their censorship. On February 24th, 2010, a revision to Tokyo’s youth welfare law was made, which included clauses that restrict the depictions of “nonexistent youths” who sound or appear younger than 18 years of age. Although the proposal was soundly rejected on June 16th — after significant protests from both legislators, as well as several mangaka and publishing companies — the governor refused to give up.

The maligned “nonexistent youth bill”, as it came to be known, eventually resurfaced as Bill 156 on November 22nd. Through both direct government action and industry self-regulation, it not only called for the restriction of works that “unjustifiably glorify or emphasize” certain sexual acts and whatever’s deemed “detrimental toward the healthy development of youth.” The new proposal specifically targeted “manga, anime, and other images”, as well as materials not necessarily “sexually stimulating”, while excluding photography and live-action content. Unlike the earlier version, however, it passed through Tokyo’s Metropolitan Assembly on December 16th, formally taking full effect as a law on July 1st, 2011.

When asked why Ishihara supported the bill at a press conference shortly as its ratification, as translated by Dan Kanemitsu, he said the following:

[I’m] not saying people can’t draw this stuff. I only approved [of this legislation] because it was about not exposing this stuff to children. It’s clear that there are perverts in this world. Sad people with warped DNA. If these kinds of people with these kinds of tastes, if they want to read and draw this kind of stuff and get excited over it, that’s fine by me, really. Although, I don’t think Western societies would tolerate such things very much. Japan has become too uninhibited. But you know, this stuff is abnormal, isn’t it?

It’s worth noting that the ex-governor’s actions, of which Kanemitsu had recorded more such outbursts for posterity, were by no means the first time anime and manga were attacked so openly. Ishihara’s sentiments, after all, were reminiscent of the moral panic that ensued in the wake of Tsutomu Miyazaki’s killing spree in the late 1980s, with otaku being smeared as embodying the perceived degeneracy of modern Japanese youth. Nonetheless, despite the significant outcry from both fans and the industry, especially over concerns of Bill 156’s chilling effect on free speech, and thinly-veiled criticism from then-Prime Minister Naoto Kan on the resulting PR damage, it seemed for a while that Shintaro Ishihara had had the last laugh.

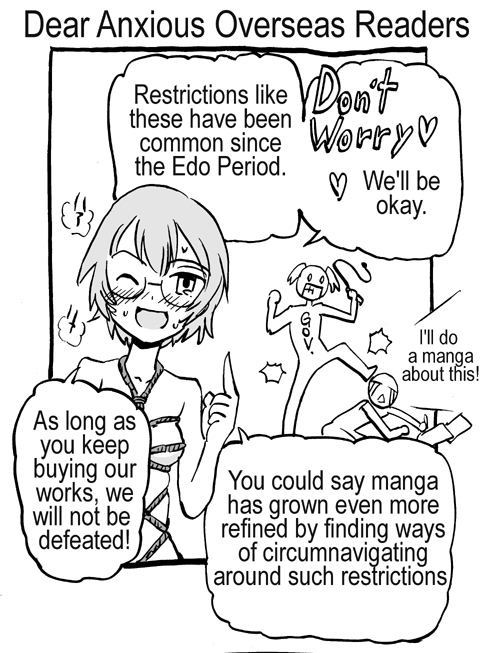

Thankfully, the worst-case scenario never came to pass. Amidst the backlash, enforcing the law turned out to be much more problematic as time went on, especially when digital sales fell outside Bill 156’s coverage. Meanwhile, not only did the anime and manga industries prove to be resilient enough to withstand such infringements on creative liberties, but it would inspire creators and otaku to become more outspoken in defense of free expression.

As more recent events have shown, however, it wouldn’t be the last time otaku would find themselves confronting the specter of repression. Whether it’s the proposed censorious revisions to Tokyo’s gender equality plans, or attempts by feminist activists and Japanese Communist Party members to push for similarly broad restrictions, echoes of Ishihara’s crusade still linger on, even if ironically coming from his political rivals. Yet if there’s any silver lining, it’s that his ultimately failed effort to save Japanese society from itself has done more to strengthen otaku than stifle them.