After the previous article which highlighted Japan’s use of money, we’re examining more contemporary cultural differences. This time we’re looking at Japan’s public education system. In the near-two years I’ve lived in Japan I’ve worked as a fulltime teacher for elementary level. Let’s jump right into it!

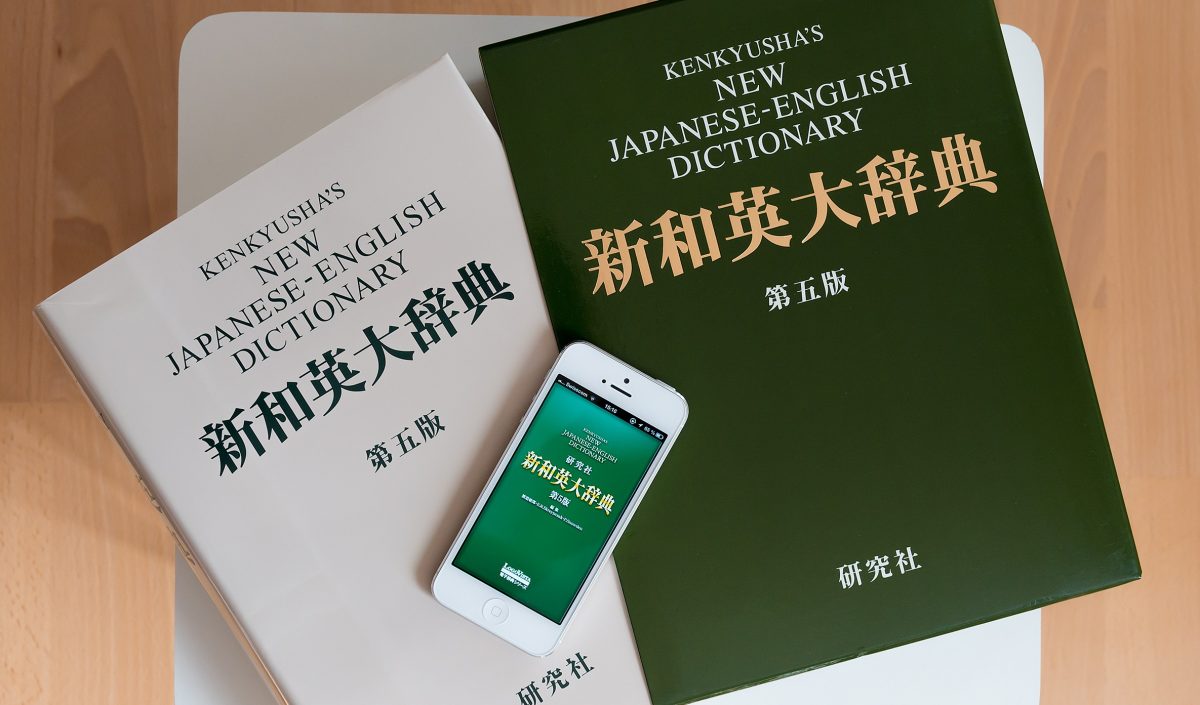

English Education Isn’t That Great

Many reports say Japan has been working to improve English education for the sake of this year’s Olympic Games, and that reason is true in some regards. However, in the grand scheme of things the real reasons are not exactly for the sake of tourism and other foreigner-targeted services.

Year after year, Japan has been credited to having some of the worst English proficiency in Asian. Usually, it is ranked below the world average of non-English speaking nations. In 2019, of 100 countries surveyed for the annual English Proficiency Index ranking, Japan placed 53rd, having dropped from 49th place since the previous year. Singapore, Philippines, Malaysia, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, and Vietnam all ranked higher.

Now, the country is in the middle of a complete English education reform. Previously, English education started in Middle School. Now, as of 2018, it begins in 3rd grade.

Teachers Don’t Raise Spoiled Brats

A sensei is a teacher not just of general knowledge, but also of life. The term applies to doctors, lawyers, and even manga artists. In Japanese schools, a sensei is sometimes regarded as a third parent, and so they teach moral education alongside regular subjects. The first two years are filled with kanji practice, reading, writing and anything else you can expect, but the main purpose of first and second grade is to teach basic manners.

Children learn to announce themselves when entering the staff room for anything, even if it’s just to walk up to a teacher’s desk and ask if they will play soccer with them at recess. Formal speech is required when addressing any school staff.

When a child misbehaves, doesn’t study, or refuses to toe the line during daily routines such as cleaning time, they are held accountable not just by their own teacher, but by any school staff who is present during the homeroom teacher’s absence. Often, even those not directly involved are held accountable as well. During incidents of bullying, not only is the bully punished but often passive students will be given a lecture for not doing anything to stop the incident themselves. No exceptions are made. No one gets special treatment.

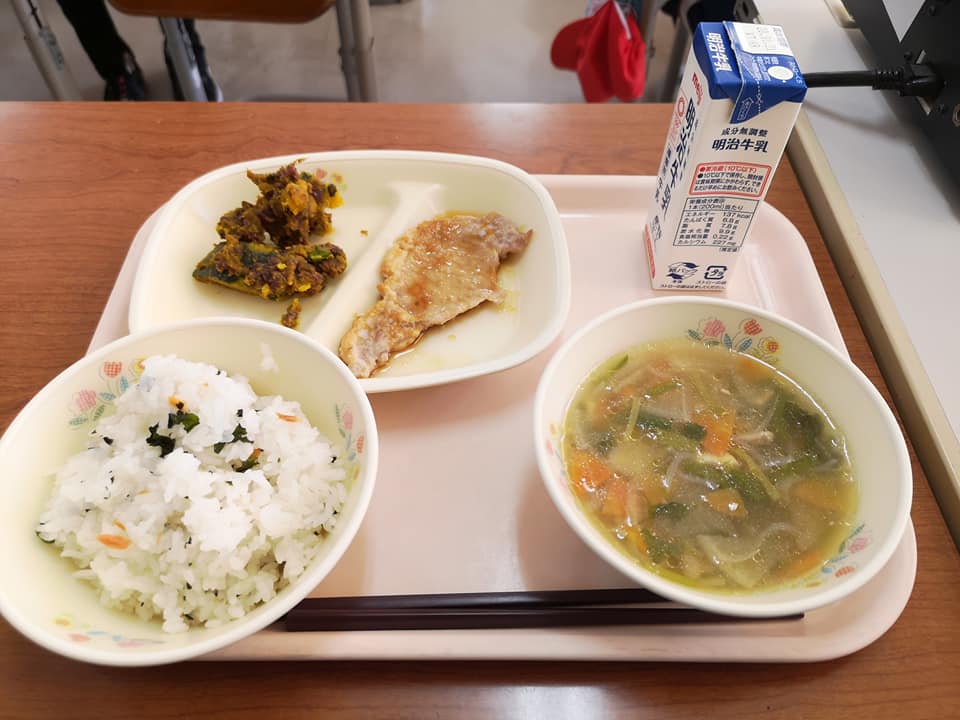

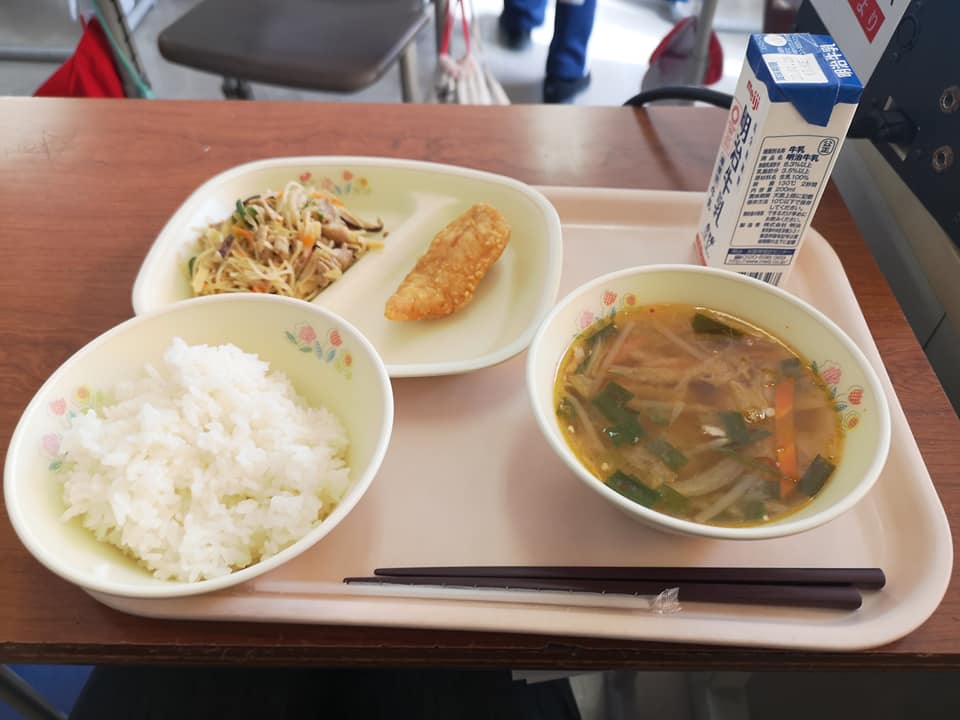

School Lunch is Almost Better Than Mom’s Cooking

Odds are you’ve heard the rumors, and they are true. Japanese school lunches are amazing. Sometimes I consider it the tastiest meal of the day, if not the week. I’ve wondered if my standards are low and Japanese people have higher expectations, but no! Almost every teacher I work with has said they absolutely love the food schools provide.

Usually, lunches are prepared at a separate facility and delivered to the school every morning. Ingredients are locally farmed, and students learn about the preparation process, local businesses that provided the food, and nutrition facts during lunch. Children are required to clean each other’s desks, serve each other, and no one eats until everyone is seated. Lunchtime is every bit educational as it is humbling, teaching children a sense of gratitude.

There is only one meal option per day, and everyone eats the same meal as everyone else, every day. Students and teachers clear their plate regardless of whether they like their food or not. Exceptions are only made in the case of certain allergies. This is why vegetarianism and veganism are practically non-existant and labeled as “foreigner culture.”

I remember the first month I started working in schools and having the same conversation with all my teachers comparing school lunch to America’s, and saying how lucky children are in this nation. Not only are school lunches delicious and healthy, but they are also cheap. My fixed rate monthly lunch fee is 5000 yen (about $50), roughly averaging out to 230 yen ($2.30) a day. In America, I remember my parents paying about $80 every month for food that tasted terrible, and that we knew was unhealthy.

All of this is in-part a big contribution to Japan having one of the lowest child obesity rates in the world.

Children Do All the Cleaning, Mostly

In elementary schools, cleaning time is after lunchtime! Younger grade levels are usually only responsible for their classroom, shoe lockers, and sections of the hallway. For Japanese schools, 3rd grade is when they are tasked with additional small areas such as the bathroom or library. Highest grade levels are tasked with everything from their homeroom to the gymnasium, and even the outside stairs.

While it’s true that students are responsible for cleaning schools, some elementary schools still have at least one janitor staff at all times. An 11-year-old definitely wouldn’t be able to handle the more heavy-duty tasks such as cleaning the school’s pool. What about maintaining the school’s garden and areas that are off-limits to student access? A janitor (and sometimes even the school principal) is responsible for such tasks.

The School Year is Much Longer

Japan loves to follow a seasonal based calendar more than anything, and the school year is a fine example. Instead of starting in late August or September like America, Japanese school years start in spring, early April (conveniently after cherry blossom season). The school year is divided into trimesters, the first one lasting until late July. Summer vacation starts then and lasts for about five or six weeks.

As I’ve been told by some of my staff, the reason schools have a suddenly long break after only the first trimester is because “it’s too hot.” Just how true that is is uncertain. Yet, heating and air conditioning are still uncommon even in newly built schools, and classrooms rely greatly on space heaters and fans.

The second trimester lasts until late December, and then the final one lasts from early January until late March, giving only about two weeks of a break before the school year restarts.

Students are Almost Never Held Back

You read that correctly. In America, students who perform poorly are allowed to retake select classes via “Zero Period” as it is sometimes called. The worst of the worst are held back a year and stay in middle/high school longer than expected, or at least attend Summer School. Japanese schools are not so forgiving. Students are almost always sent forward to the next grade level regardless of passing or failing grades. There are no make-up courses or zero-period retakes, except in high school, depending on a student’s circumstances. The final decision for these students is left up to the principal! Students almost never get second chances.