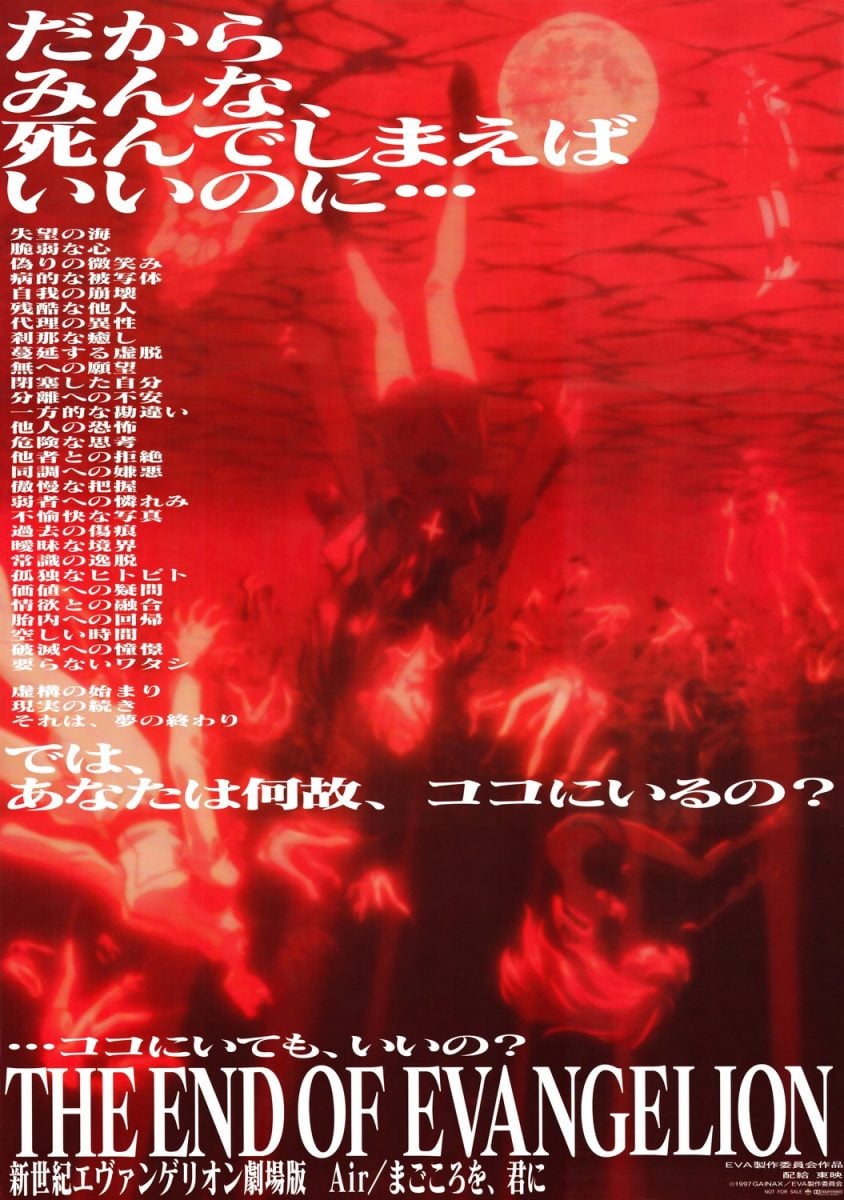

It’s been said that to really appreciate Hideaki Anno’s now-classic Rebuild of Evangelion films, you have to have seen the original Neon Genesis Evangelion from the 1990s. This is especially the case for End of Evangelion (1997), which has over time gained both acclaim and infamy among anime fans. If anything, it’s a haunting victim of its own success.

Alongside the preceding Death and Rebirth compilation (1997), the last 24 minutes of which form the basis for the first third of EoE, it elevated Gainax, and Anno to new heights. These heights were, unfortunately, marked by deep lows. From budget issues, concerns over creative control, or the director’s mental breakdown, it’s miraculous that the film came out the way it did. Getting 2.47 billion yen at the box office, its impact would reverberate long after its premiere, for better or worse.

Going past the accolades, and its historic significance, you might be wondering: after nearly 25 years, is this 87-minute romp still worth checking out, or just a case of LCL-tinted glasses? Having already glimpsed the other grand finale, 3.0+1.0: Thrice Upon a Time (2021), this deserves a look.

The movie’s original theatrical trailer showcases Anno’s earlier forays into live-action. Circa 1997. (Source: YouTube)

Tumbling Down

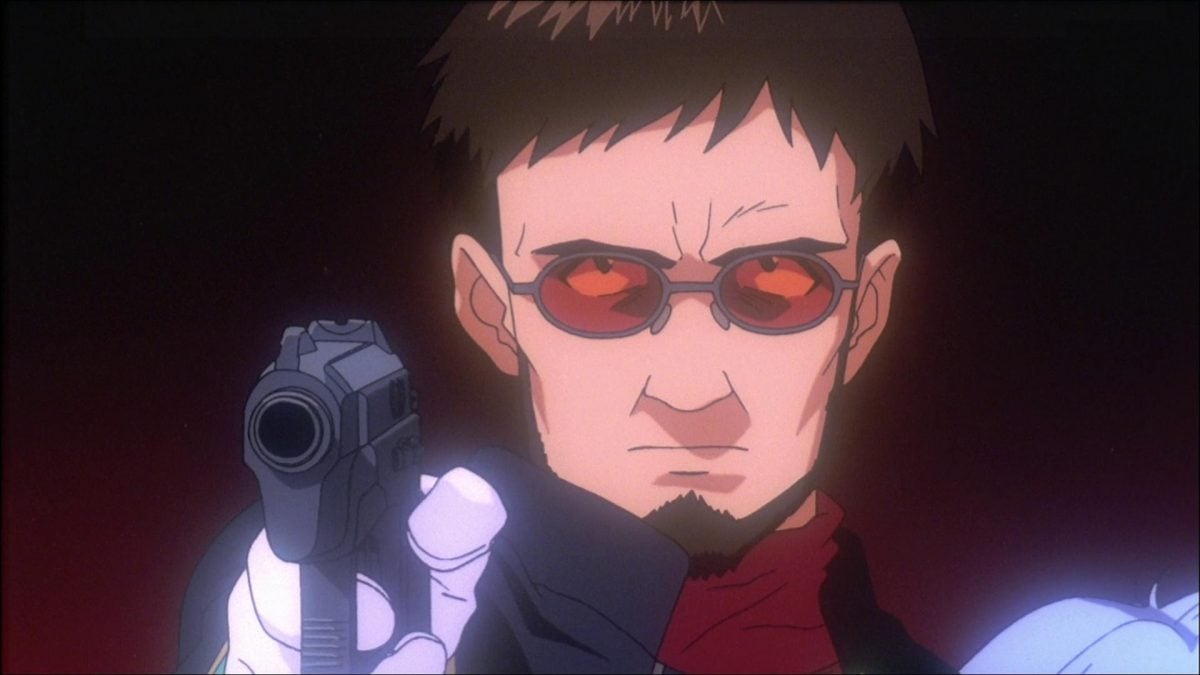

Expanding on Episodes 25 and 26 from the original TV series, End of Evangelion follows a distraught Shinji Ikari (Megumi Ogata, Spike Spencer, Casey Mongillo) as he visits a comatose Asuka Langley Soryu (Yūko Miyamura, Tiffany Grant, Stephanie McKeon). Meanwhile, SEELE catches on to Gendo Ikari’s (Fumihiko Tachiki, Tristan MacAvery, Ray Chase) real plans for Third Impact, and quickly accelerates its schemes. Chaos, bloodshed, and tragedy ensue, as plots and prophecies converge. All culminating in the Human Instrumentality Project. Make no mistake: the end has come, and no one is ready. Most especially Shinji.

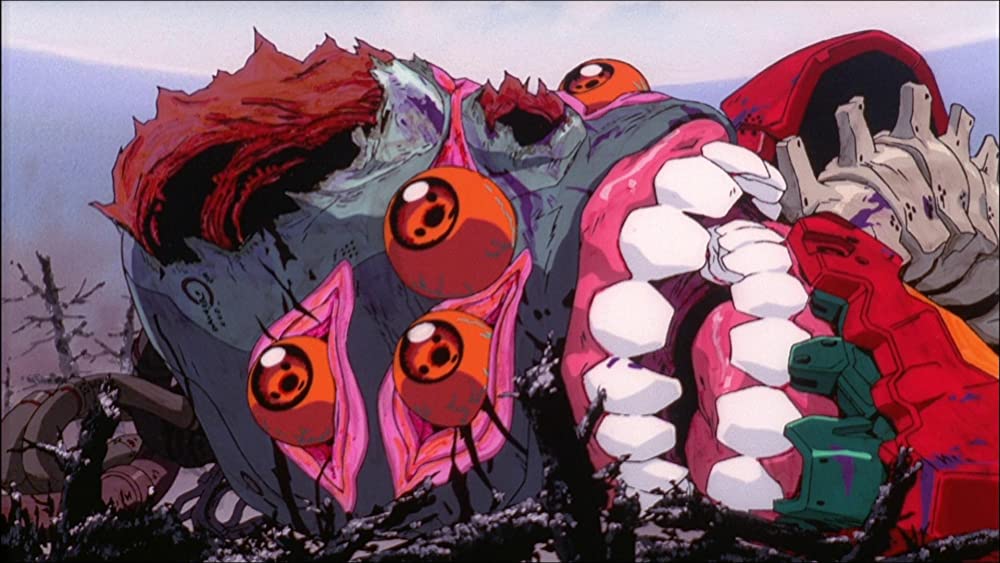

If there’s one thing that EoE does exceptionally well, it’s in how it drives home its bleakness. The assault on NERV by the JSSDF soldiers who once aided it in fighting the Angels is relentlessly brutal. Meanwhile, as the world around our hero continues tumbling down, he comes off as either self-loathing or nigh-catatonic. It only gets worse from there, with no respite in highlighting how powerless anyone is in such a harrowing situation. Even the more cathartic moments, whether it is Asuka’s valiant stand against the mass-produced EVAs, or Gendo getting his dues, seem to exist just to be yanked out from under any sense of hope.

This pervasive nihilism speaks volumes to the state of mind among the staff. Much has been said over the years about how the anime’s production grew increasingly troubled. It’s known how Ogata went so far as to actually strangle Miyamura to get a proper take, and that Anno himself wanted to show real fanmail and death threats during the infamous Instrumentality sequence, only to be denied for legal reasons. Given how the Gainax staff at large were otaku, the director’s conflicted sentiments towards fandom, and his publicized struggles with depression, it’s unsurprising that such a dark film coalesced. Even the much-debated ending can leave you empty and asking questions.

Yet those circumstances help elevate EoE beyond being just another anime movie. For all that nihilistic flair, which some longtime fans perceive as being realistic, the Evangelion spirit is still present. Though it may take more than a few viewings to grasp every bit of symbolism — from callbacks to the original series to a nod towards Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End — much of the cast gets ample screentime and resolution, violent or otherwise. There’s purpose in just about every scene, from the unnerving sterility of the hospital room, to the surreal imagery as Third Impact ensues. It’s a finale that befits the original series.

In hindsight, it’s a mirror image to the much later Thrice Upon a Time, complete with an overarching theme of escaping from and returning to reality. Though, unlike that other grand finale, EoE offers little consolation or hope, though the emotional poignancy remains as strong as it was back in the ‘90s.

An Impressive End

One other aspect of EoE that stands out is the visuals. In contrast to the notoriously cheap production values by the end of the TV anime, Gainax goes all-out in giving the apocalypse its proper due. While retaining the same style from the series, the attention to detail is impressive, down to the debris and gore. Combined with the crisp animation and choreography — especially when it comes to the EVAs in motion — it becomes especially stunning. Even at its most surrealistic, complete with a live-action snippet, it really showcases what Anno’s capable of when given free rein.

The anime’s crisp movement and cinematography remain as good in the 2020s as they were in 1997. (Source: YouTube)

Even with the turbulent circumstances, the audio shines through. Shiro Sagisu’s soundtrack meshes ethereal pieces, ominous motifs, and dissonant renditions of Bach together into a sensory assault that’s as beautiful as it is haunting. The voice acting, at least regarding the original seiyuu and the ADV English dub, likewise comes off strong. While still consistent with their performances in the original series, there’s also a particular rawness in how lines are conveyed, especially when it comes to Shinji’s slide into utter madness. Granted, it’s not exactly pleasant to hear, and the Netflix version doesn’t come off as well as the previous localization. Yet put together with the OST and visuals, and it’s bound to stick with you.

This is (Not) the End

For its day, End of Evangelion marked a high point for Anno’s career, even as his personal life remained at deep lows. This contrast would define its reception from its release onwards. As put by editor Carl Gustav Horn, while it earned critical and popular acclaim — including the Japan Academy Prize for “Biggest Public Sensation of the Year” in 1997 — others regarded it as “more a product of the madness of crowds”.

Produced not long after the movie’s premiere, this old NHK documentary captures Hideaki Anno as he’s slowly recovering from depression, which would eventually influence the Rebuild saga down the line. Circa 1999. (Source: YouTube)

As much as it remains hotly defended and rebuked to this day, its undeniable impact proved to undermine EoE’s intention of bringing closure to the franchise. Instead, like the TV series, it became something of a benchmark. On the one hand, this could be seen in the proliferation of Evangelion merchandise and spinoffs, as well as the emergence of conventions like the Rei Ayanami Expy. On the other hand, there were those like producer Toshimichi Ohtsuki, who in 2006, not only accused the series’ success of cultivating “the mass development of inferior works” but controversially blamed it for the popularity of moe works like KyoAni’s The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya (2006), and in his eyes, the end of the anime industry. Anno, meanwhile, was uncomfortable with how people apparently missed the point. This eventually set the stage for the Rebuild films and his second grand finale.

For what it’s worth, though, you’ll find much to appreciate in this movie. Love it or hate, if it’s a victim of its own success, then at least it’s a phenomenal one.