One of the most well-known and notorious quirks of Japanese nerd culture is the existence of doujinshi. Whether it’s original homebrew games, fan comics, or those of the erotic kind, it has become such a mainstay among otaku that it’s unlikely to fade away anytime soon. Japan, however, wasn’t the only country to have conceived doujinshi. Well before the first Comiket was held, the United States saw its own homebrew share of doujins, known as “Tijuana bibles.”

Although the term itself was said to have emerged in Southern California in the late 1940s, though they were neither bibles nor originated from Mexico, these peculiar comics (also known as “eight-pagers” and “bluesies” to name a few) were infamous for often being pornographic parodies of established works of the time. Often poorly printed and usually on 4’’ by 3’’ colored pages, they gained popularity during the Great Depression. By the 1960s, however, they had faded away into obscurity, though not before setting the stage of the emergence of underground and indie comics in the West.

To truly understand the significance of Tijuana bibles and why they failed where Japanese doujins succeeded, however, you have to go back in time.

The Past is Another Country

America in the early 20th Century was a wild ride in terms of comics. Creators were jumping onto the possibilities provided by newspaper strips and the emergent comic books. Even though this era saw the rise of media moguls like William Randolph Hearst, it was also a proverbial Wild West in terms of copyright and what could actually be published. In a sense, those days weren’t too unlike how Japanese manga as it’s known today came to proliferate. So, it’s not too much of a surprise that by the 1920s, parodies and explicit fan works of established material began surfacing.

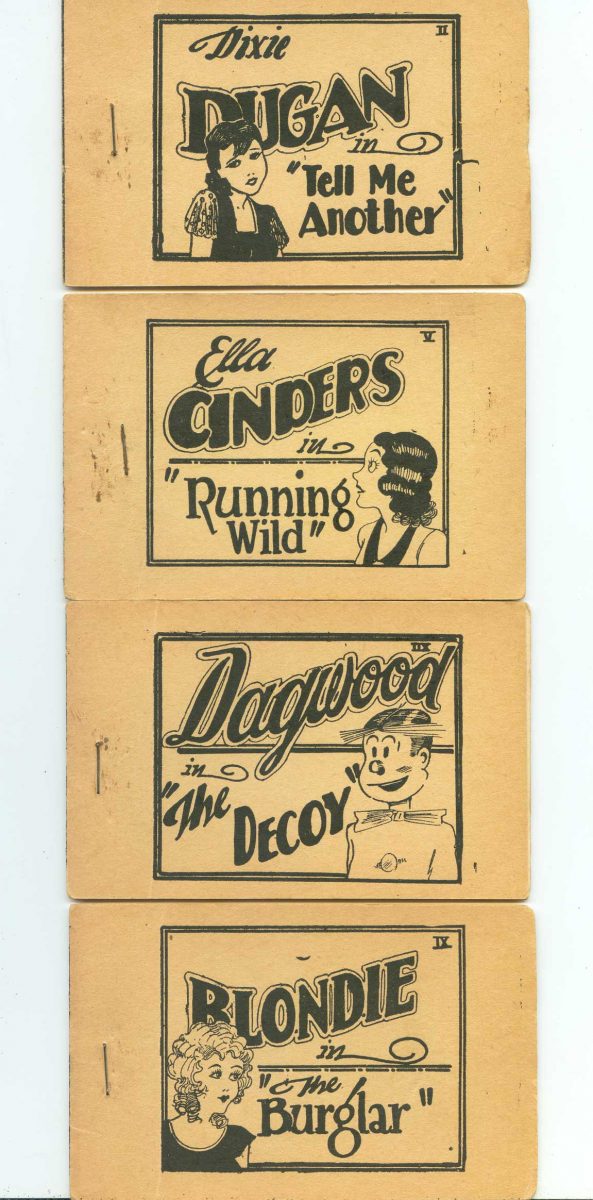

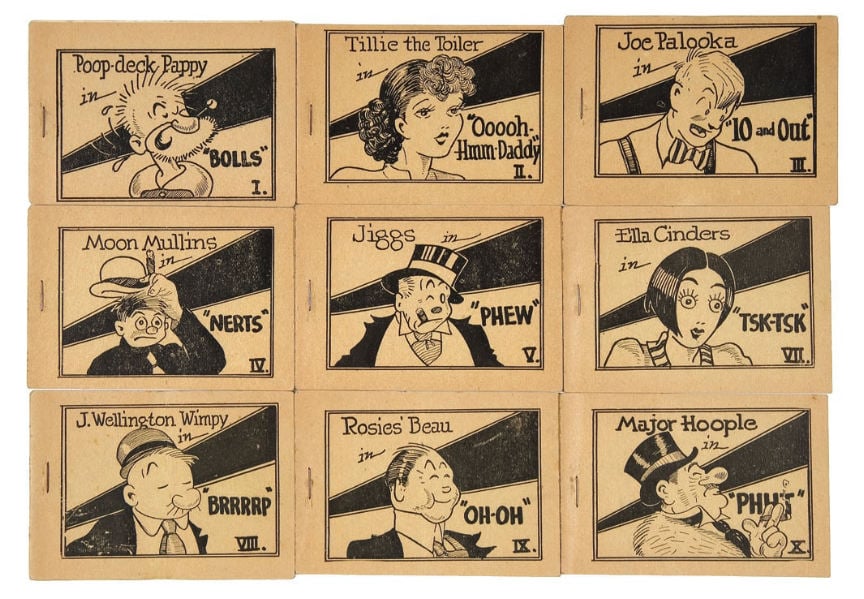

It’s unknown who actually made the first Tijuana bibles, let alone where they emerged. What’s certain, however, is that the earliest known examples date back to around 1925-26. Traced to Midwestern states like Indiana, these starred then-popular characters such as Tillie the Toiler, as well as Jiggs and Maggie from the strip Bringing up Father (1913-2000). It didn’t take long, though, for more to pop up throughout the country by the dawn of the Great Depression. This was achieved through a combination of various local printing circles (in cities like New York), and distribution networks as varied as railway, mail, and simply stashing copies in automobiles. In an era when you could get away with illicit activity across state lines, to say they took off was an understatement. Over the course of decades, according to cartoonist Art Spiegelman, about 700 to 1,000 distinct bluesies were estimated to have been made, with millions of copies sold.

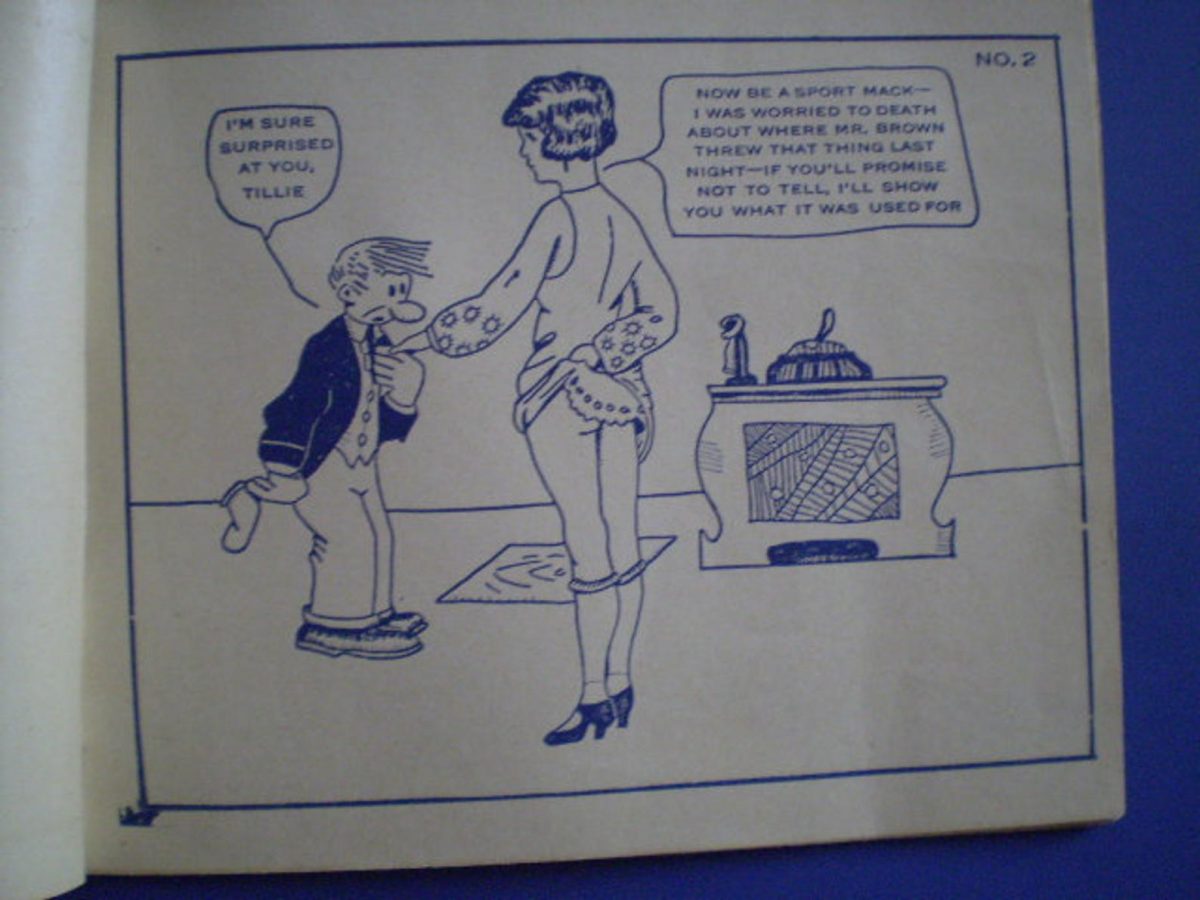

What’s rather surprising about the eight-pagers (which weren’t always eight pages long) are the parallels with their spiritual descendants. For instance, they generally featured various fictional comic characters and the real-life celebrities of their day, whether it’s Popeye, Blondie, or the infamous mobster Al Capone. Original characters were not unheard of. These parodies also (in a time not normally associated with lewdness) catered to all kinds of erotic tastes. At their best, the artwork and covers managed to mirror their source material rather well, which in turn made the hijinks all the more worth looking at. And while it’s uncertain whether these publications were purely “mom and pop” affairs or a Mafia-financed operation at some level, the clandestine distribution networks allowed for a sizable market to emerge. The rarer variations, which had sixteen or more pages and generally higher quality, were even sold at premium prices.

The selling of eight-pagers throughout their existence were discreet, under-the-counter fare. Though places like Times Square — where covert, hole-in-the-wall shops were fairly common due to its then sleazy reputation — would have been the closest approximate to Akihabara, most “sales” were done in schoolyards or alleys. In addition, compared to the tendency among Japanese doujin artists to use aliases, American creators didn’t leave any names whatsoever. While Wesley Morse, who went on to make the classic Bazooka Joe comic strips (1953/54-2012) after the Second World War, was long since identified as having created his fair share, the vast majority remain unknown; for this reason, later collectors came up with nicknames like “Mr. Prolific” and “Blackjack” (both active in the 1930s) to tell specific creators apart. Although speculation still exists on who some of them were, with Mr. Prolific believed to be cartoonist-turned-US Army officer “Doc” Rankin, according to artist Tom Christopher among others, the truth may forever be lost.

All the same, Tijuana bibles were a phenomenon at their peak. Not only were they recognized by more than a few established creators, but as far as it’s known, no one had the bluesie artists prosecuted. Indeed, Al Capp (creator of the classic Li’l Abner) was known to have remarked how he knew he’d hit it big when Tijuana bibles starring his own characters were being made. On top of that, they provided much humor and entertainment to many Americans, especially amidst the hardship of the Great Depression. While not necessarily political in nature, they also provided a liberating outlet for creators to express more transgressive views, and not just in their irreverence. One eight-pager from 1939, “That Nazi Man”, even ended with a rather serious plea against anti-Semitism.

The sky, even if only for a moment, seemed the limit. Given enough time, it may well have followed down a similar path to how Japanese doujinshi evolved.

The Times are A-Changing

It now begs the question: what was it that killed off Tijuana bibles? Why didn’t an American doujin scene truly come into its own?

The most common explanations often attribute the decline to the Second World War and the emergence of glossy publications in the years after, whether it’s Mad Magazine or the likes of Playboy. There’s much truth to that. Many of the artists behind the eight-pagers would have wound up serving in the military, and may likely have either perished in combat or quietly “retired” altogether. Meanwhile, there’s greater incentive to simply produce content through the magazines, due to their perceived legitimacy, even amidst the changing tides of public opinion. Which isn’t getting to the generally lower quality of the postwar content. This was particularly seen in the sloppy work of “Mr. Dyslexic” (active around the late 1940s-50s), according to both Christopher and Spiegelman; this artist gained notoriety for his mean-spirited diatribes and a penchant for butchering the English language. These alone, however, weren’t the only reasons why the dream ended.

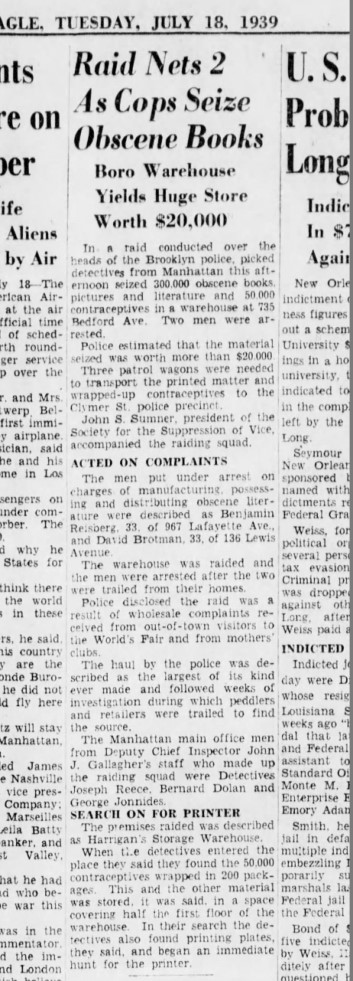

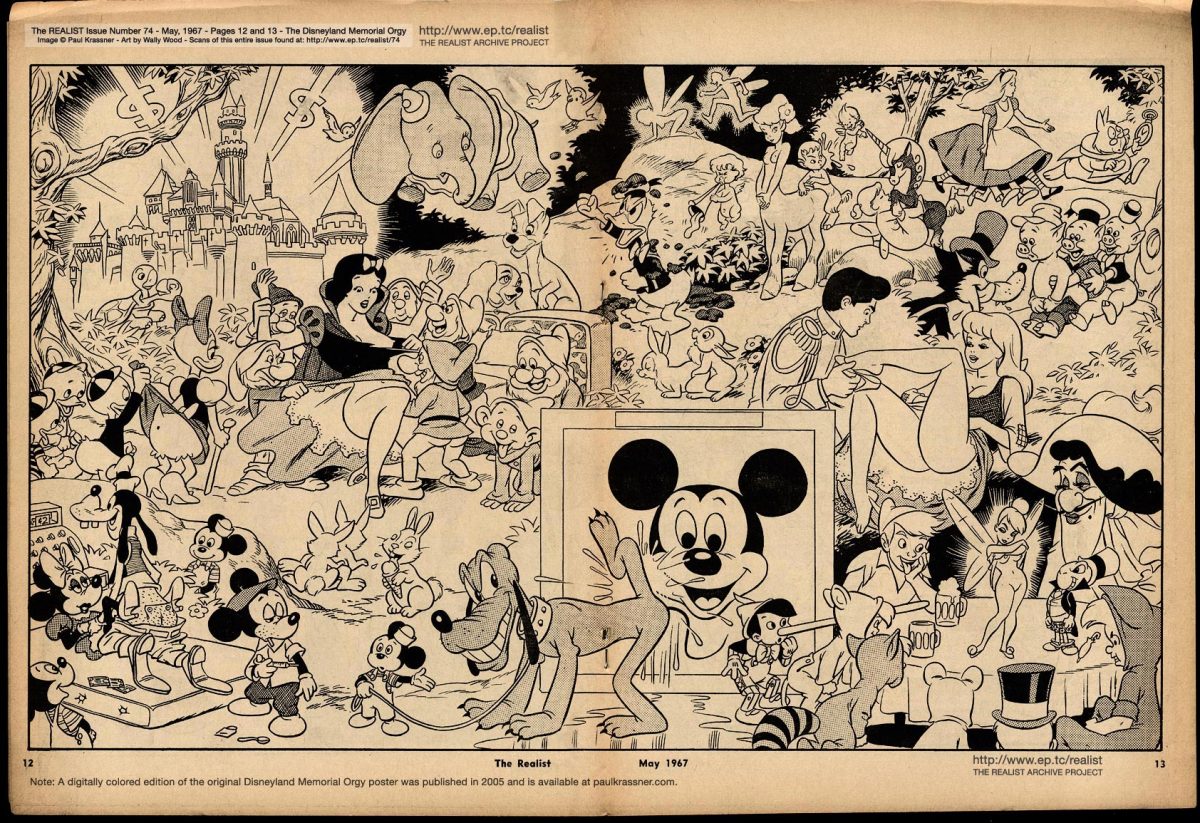

More than social stigma, the law plagued Tijuana bibles almost from the very beginning. Not everyone was pleased with the existence of bluesies, whether it be moral guardians offended by such irreverent material or the likes of the Walt Disney Company none too happy with their intellectual property being violated, often literally. As early as the initial wave in the 1920s, police raids weren’t unheard of. Among the more notorious cases on record involved the NYPD trailing men selling eight-pagers at the 1939 World’s Fair to a Brooklyn warehouse, with 300,000 printed materials and equipment seized. Though local groups could mass-produce copies as long as they had access to printing equipment, by the 1940s this proved more unsustainable thanks in no small part to the FBI. And unlike Japanese doujin creators (whose access to photocopying in the 1970s is said to have spurred a resurgence for doujinshi), their American counterparts were running out of viable options. This proved to be a blow they’d never recover from.

The moral panic around comics, which emerged in the 1950s and was epitomized by Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent in 1954, also endangered Tijuana bibles. Fears of both widespread public backlash and direct intervention by the US Government over “juvenile delinquency” led to the establishment of the infamous Comics Code Authority that very year. The comics industry in North America, and to a degree the Anglophone West at large, would be changed forever, stifled under censorious policies that leave echoes even to this day. This all but killed off what remained of the eight-pagers, as they represented in a sense everything that was deemed unacceptable for the American youth. Suffice to say there was little incentive anymore for those still staying the course to continue on, their works devolving into little more than obscure adult novelties by the early 1960s before quietly disappearing altogether.

Then, there were trends in US copyright enforcement by then that ensured that the bluesies stayed dead. The efforts by Disney, in particular, to influence copyright law in America became pronounced enough that its lobbying led to Congress passing the 1976 Copyright Act. More than just extending the duration of protection for published works before entering the public domain, especially Mickey Mouse, this also defined the “specified factors for courts to consider in determining fair use” for the first time. It also meant that parodies of existing IPs, erotic or not, could be denied fair use should they be deemed a “market substitute.” Coupled with the passing of the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998, which further prolonged copyright protection for corporate works to the benefit of Disney, this effectively made the prospects of a homegrown American doujin industry illegal and nigh impossible.

It’d be a no-brainer to conclude that the end came with a whimper. Though that’s not quite the end of the story.

Legacy

Although Tijuana bibles’ time in the sun has long since passed, they’re not forgotten. As early as the 1970s, there were efforts by some artists and collectors to preserve such relics. It’s also no surprise that, according to some commentators, the eight-pagers helped inspire the emergence of the underground “comix” industry during that decade, as well as the wider independent comic scene over the 1980s. Indeed, Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill even created an authentic recreation for The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier (2007), parodying George Orwell’s 1984. It wouldn’t be until the rise of online publishing and Internet fandom, however, that the idea of fan comics (especially of the Rule 34 variety) would once more gain wide enough traction.

Unfortunately, the existing laws and cultural environment in the US help ensure that such developments would by necessity stop short of bringing back an American doujinshi scene. Whether or not this state of affairs changes in the future, there’s at least some consolation that the spirit is alive and well in Japan.

You need only look across the Pacific to see what could have been.

![Ganbare Doukichan Episode 12 [END] Kouhaichan Doukichan Maid Hearts](https://bimgs.jlist.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ganbare-Doukichan-Episode-12-END-Kouhaichan-Doukichan-Maid-Hearts.jpg)