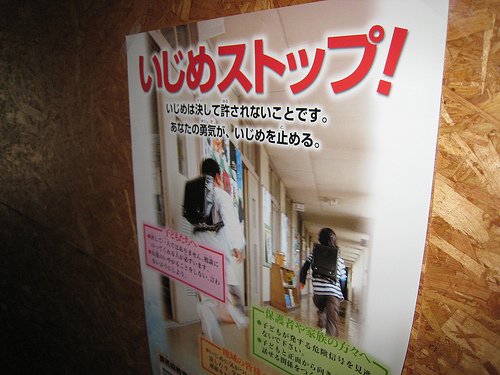

The other day I went to my son’s school to watch the various end-of-year performances the students had prepared for the parents, which included putting on a puppet show and school TV news report all in English, and the entire fifth grade performing a symphony concert for us, too. While I was walking through the halls, I noticed a big poster that said “STOP THE IJIME” with the slogan “we cannot allow bullying to continue — your courage will end it forever” written below. It’s a sad fact that ijime (ee-jee-MEH), the bullying and hazing that happens in schools, is a major social problem here in Japan, and all too often it’s given as a the trigger leading to a young person’s untimely death. There are several reasons why ijime is such a problem in Japan, beyond the bully-before-you-are-bullied mind-set that is probably present in all kids to some degree. First of all, the Japanese custom of keeping classes of students together all day throughout the school year, with teachers coming and going each hour, might be good for imparting group cooperation skills for forming lifelong friendships, but it also amplifies problems between students. If you have to sit next to a cruel jerk for one hour a day you could probably get through it, but all day, every day, for a whole year? Teachers also sitting together in a large room rather than individual offices is a problem, too, since it makes it difficult for a student to talk to one teacher, especially bad when a teacher is part of the problem. Finally, the near total lack of counseling and therapeutic medicine is also part of the problem, and all too often all kids can do is that most Japanese of activities “gaman” (meaning to endure patiently).

Each language is special, with unique features that may cause confusion for speakers of other languages. Romance languages like Spanish and French have noun genders, forcing English speakers to puzzle over why a pen is feminine while a pencil is masculine. Although Japanese do consider it a point of pride to think of their language as being especially hard to learn, I am convinced that no language is intrinsically more or less difficult than all the others. Still, there are some barriers to learning Japanese that must be overcome, starting with the two syllable-based writing systems, hiragana (the wavy looking one) and katakana (the boxy, masculine looking one), which you can tackle by memorizing the shapes and what sound they make (we can help). Kanji is also no small challenge, although you’d be surprised how much you can read with just a few hundred characters under your belt after a year or two of study. Grammatically there are some confusing areas, such as having to get used to two different verbs for to be (in a place), aru (ah-ROO) for inanimate objects, and iru (ee-ROO) for anything that moves, like people or animals. Whenever you learn something new, it’s important to test it to find the limitations on that new piece of information so your brain can internalize it, and I remember bugging my sensei about which verb was correct for objects like zombies, cyborgs, and Venus Fly-Traps.

There are times when the Japanese seem to be the most expressive people in the world to me. First of all, the fact that nearly everyone has taken several years of English allows for Japanese to use the language as a tool of expression without letting all the biases against bad grammar and meaningless words get in the way. This leads to the Japanese being able to create new English words to fit their needs, like Balance Up (a calorie balanced snack), Wordtank (Canon’s popular electronic Japanese dictionary), Meltykiss (delicious fudge squares, love ’em) or the famous Walkman by Sony, which had to sound really silly the first time you heard it. They’re also able to express more when writing text on a computer or cellular phone, since Japanese is a two-byte language, allowing fonts to go beyond the limits of mere ASCII, adding everything from musical notes to common symbols as standard characters. Finally, the tradition of putting kana above kanji to show how it should be read is often extended in innovative ways. In Yu-Gi-Oh, for example, they can put an unfamiliar word like Black Magician in English and write tiny kanji that explain the meaning above it, creating a single gestalt for the eye that performs both functions. Similarly, someone translating a Harry Potter novel might use the English word Quidditch but write characters for “air broom ball” above it in kanji, making all aspects of the word instantly clear at a glance.

We’re happy to have our Domo-kun T-shirts and warm hoodies back on the site for you, and J-List customers seem very happy to have them available again. We forgot to mention that our hooded sweatshirt now includes an XS size — a first, since this color is usually not available in this size — making Domo-kun a great item for customers needing youth sizes.

We love to bring you fun an interesting things from Japan, and today we’ve got Fresh Cuts, an outstanding collection of the most interesting indies music from Japan today, brimming with 16 tracks by bands like Baggy Chopper, Maria Gadet and Guitar Vader. It’s in stock in San Diego and ready for your order.