Some of the biggest differences between Japan and the U.S. can be seen in higher education. Japan has an extensive system of public and private universities which educate 44% of graduating high school students. In the U.S. the top universities are private schools like Harvard, Princeton and MIT, while State schools are lower in the rankings. In Japan this is reversed: the public universities are where everyone wants to go, in large part because they’re much cheaper than their private counterparts like Waseda or Keio. Students study hard to get into top-ranked national institutions like Tokyo University at least in small part to lessen the financial burden on their parents and show oya koko (filial piety, e.g. thanks and respect to their parents for raising them). While Japan’s national universities might offer a good education, they’re dependent on the public purse for their operations and are generally running out of money all the time. A visit to some of these campuses with their drab brown concrete buildings built in the “Late Contemporary Chernobyl” style can make you think you’ve been transported to the old Soviet Union. The money problem has gotten so bad that some schools have started licensing their name — if you want to try a Kobe University- brand steak, you can find them for sale in finer shops. One of the biggest problems with Japanese universities is that students must work so hard to pass the entrance exams that it’s generally expected that they’ll goof off once they get admitted. This makes me sad, considering all the ways my mind was challenged during my own time at college. Another problem: too many universities. Despite the sagging Japanese population and dearth of students, new universities continue to be built every year.

I really enjoyed my career as an ESL teacher, and during that time I came into contact with many different kinds of Japanese people, from kids who were being exposed to English for the first time to high school students who wanted to learn how to actually use the language they’d spend six years learning the grammar and vocabulary of. I always tried to show a positive, cheerful face to my students (Japanese people expect Americans to be “cheerful” at all times, I’ve learned), and let them know how great it is to learn English, since it allows you to make friends all over the world. I’ve met interested students, bored students, and housewives who thought that studying English was the most thrilling thing in their lives (clearly they needed to get out more). I’ll never forget one student I had who drove a tanker truck delivering white kerosene to gas stations. Whenever he couldn’t communicate something in English, he’s try saying it in Japanese with an outrageous American accent. It’s not considered good form for the teacher to laugh himself into a ball during class, but it was difficult keeping my amusement bottled up sometimes.

The subject of how men and women interact in Japan is a complex one, and I’ve come to realize how closely related it all is to language, despite the obvious “which came first, the social attitude or the linguistic term” question. For the most part, English is largely unisex, with the same words being used by both men and women, with a few exceptions (like profanity). Japan is quite different, and much of the language is “hard wired” for use by women or men only. For starters, there are different pronouns for boys and girls to use. Guys generally use the polite “boku” or the manly-sounding ore (OH-ray) to refer to themselves, but girls get the more feminine watashi or atashi (or if they’re trying to be annoyingly cute, they refer to themselves in the third person, like characters sometimes do in anime). For the second person pronoun, men often use masculine omae (OH-mah-aye) or the slightly condescending kimi, both of which contain an element of talking to someone at a lower social level, like an underclassman. Women usually use the neutral anata, and both sexes will often substitute a name, e.g. Fujita-san, in place of a second-person pronoun. There are quite a few words which the Japanese use every day but which sound incredibly sexist if you analyze their actual meanings. The most common word for husband is shujin, which really means “master” if you look at its kanji. Two words for wife used by older Japanese are kanai (lit. “in the house”) and okusan (“Mrs. Interior”), implicitly stating that wives never leave the home. Of course, these are just words and no one considers their meanings all that deeply, just as we don’t tear English words apart for their Greek and Latin origins that much, but it’s interesting what you can uncover when you dig deep into a language.

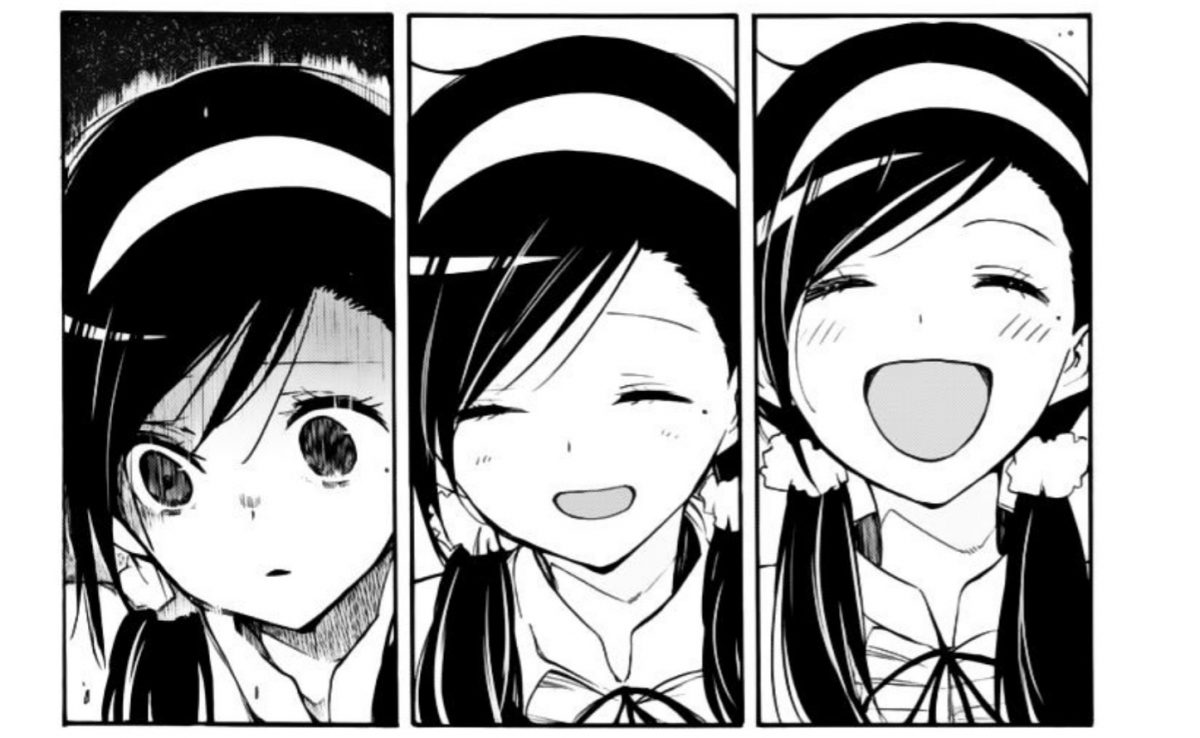

J-List loves to bring you the best PC dating-sim games from Japan, translated into English. We’ve got dozens of great CD-ROM and download games for all tastes, with hilarious stories, extremely dramatic love themes and all manner of cute characters. Our latest game is Doushin – Same Heart, a fascinating title in which you play from the viewpoint of the three Suruga Sisters, Ryoko, Maki and Miho. At any time in the game you can “zap” from one character to another and continue the story from their point of view, which adds an incredible element of depth to the story. A great game by Crowd, the company that brought us X-Change, X-Change 2 and Tokimeki Check in!, so we know it’ll bring you many hours of enjoyment (and lots of in-jokes from the other games). It’s being duplicated right now, but you can still order now and get free shipping on it!