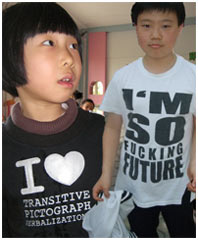

Like many other English speaking gaijin, I came to Japan as a teacher of ESL, imparting my native language to students as young as three and as old as 88. I taught high school students who wanted to study in the U.S., engineers who needed to use English for their jobs, bored housewives who studied English as a hobby and even the wife of the founder of the Sapporo Ramen Company. There were some things I had to get used to as a teacher, including how to answer when my students asked me “why” a certain grammatical point worked the way it did. (“Um, because infinitive verbs just like things that way.”) I also had to get used to some of the outrageous Engrish T-shirts my students would wear to class and keep from laughing during class. Just as Westerners appreciate the aesthetic beauty and inherent awesomeness of kanji on T-shirts — we’ve been known to sell one or two of those — Japanese love to decorate their clothes with English, although they’re seldom concerned with the meaning. I’ve been told that the reason no one bothers to understand what phrases like “I feel happiness when I eat a potato” or “Cutie Welcomes Girl Paradise” mean is, “Japanese don’t think deeply about such things.” They don’t think deeply about the Playboy bunny, either, and it’s quite common to see school-age students wearing clothes with the iconic logo on them, with no idea what it means other than that it’s kawaii. Decorative English is used in marketing of products, too, for example the ubiquitous statement that “this product uses the finest quality ingredients” on every can of Japanese beer. When you open a package of that delicious Fit’s Gum from Lotte, you’re greeted with a funny Engrish guide to “how to chew Fit’s gum” that’s so cute.

By the way, I should point out that a lot of the really bizarre Engrish you see on the Internets comes from China rather than Japan these days. You can easily tell the difference between the two languages by noting whether written characters in any image use kanji only (indicating that the language is likely Chinese) or if they also mix in hiragana/katakana characters (which are only found in Japanese). The Japanese staff of J-List specifically asked me to include this, since they don’t like some of the really bad English used by the Chinese to be attributed to them.

T-shirts in Japan can be very, ah, creative.