Given the sheer amount of manga and anime produced, it may come as a surprise that there has been no widespread effort to preserve them for future generations, nor are they classified as “Cultural Properties” by the Agency of Cultural Affairs. That hasn’t stopped a Japanese politician, Yamada Taro (referred to as an “otaku politician” by Niche Gamer), and members of the “Manga, Anime, Game Parliamentary Federation” from drafting a bi-partisan bill pushing for the creation of a “National Center of Art and Media.” This also includes the preservation of manga and anime.

Japanese video showing Yamada Taro discussing the proposed “Manga Bill” and its importance. Circa 2019. (Source: YouTube)

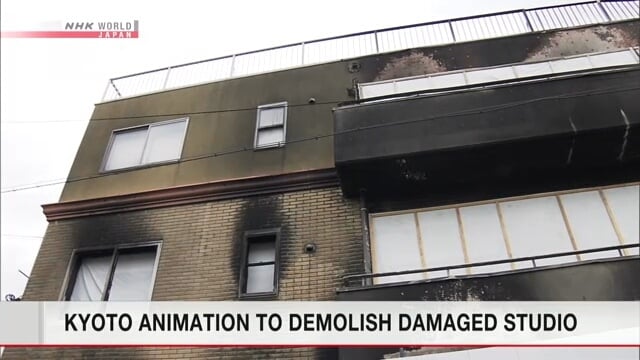

According to outlet Kai-You and Irodori Comics CEO On Takahashi, the proposed legislation (unveiled on November 26th, 2019) was made so as to ensure that the creative works by Japanese creators, especially manga and anime, would never be “lost” due to disasters. The proposal was also made in the wake of the tragic arson attack on Kyoto Animation, destroying several files and resources on top of casualties, and the flooding of the Kawasaki City Museum by Typhoon Hagibis in October, with 260,000 pre-war comic books and paintings thought to be lost. In the case of KyoAni in particular, it’s mentioned that had its servers been damaged, “then works that have been accumulated for nearly 40 years, those precious materials about the work would be forever lost.” It’s little surprise, then, that the studio has wholeheartedly pledged to support the initiative, with others perhaps to follow.

At a glance, this may seem like something that would garner popular support. As On Takahashi remarked, however, there are certain hurdles. On the one hand, there’s the possibility that the proposal may not be passed by December 9th (when the Diet is set to close for the year) due to politicians having milked the KyoAni arson for all it’s worth that they may lose interest and move on to other matters like the upcoming elections and 2020 Tokyo Olympics. “If this bill doesn’t pass the vote by then,” as claimed by Taro, “it is most likely going to be scrapped.” Unfortunately, if one of his recent comments are any indication, it appears that the proposal was unable to be brought up on that day.

On the other hand, there’s the observation that Japanese companies and creators simply don’t keep their data consistently, if at all. The stories, for instance, of Square Enix having long since lost the source code for its older games, are sadly not uncommon. As On Takahashi noted, this has less to do with negligence and more with how hard drives have historically been more expensive:

You might be shocked at Square losing the code for one of their most famous games, but episodes like this aren’t rare. There are reasons why some manga never make it overseas. Because a lot of artists just “lost” their data.

For older works, artists and mangaka never considered foreign publication. So once they’ve made the work and submitted their data to the JP publisher, a lot of them deleted the files to “free up space on their PC.” This was before hard drives were cheap.

So years later, when foreign publishers approach the artists for their data to localize it, a lot of them say “Sorry, I can’t seem to find it.” or “Oh yeah, I deleted that.” Even with Irodori Comics there are cases where artists just don’t have the data.

Nonetheless, even with such concerns, there are still hopes that the Manga Bill may be passed into law. Whatever happens, the need to find some means of preserving generations of Japanese creative work, including anime and manga, for posterity has been long overdue.

Yamada Taro had previously proposed legislation formally ending the long-standing censorship clause on pornography in Japan.

Special credit goes to On Takahashi for having broken this development in English, as well as Niichiban/Niche Gamer for its coverage on the situation.