When it comes to fans of Japanese anime and manga beyond the Anglophone world, few would arguably compare to French fans. Even among other Europeans, it doesn’t take much to see why French otaku stand out, whether it’s the sheer number of anime broadcast in the country, the popularity of events like Paris’ Japan Expo, or the bountiful presence of manga even compared to the time-tested bande dessinée (Franco-Belgian comics) industry. It’s reached the point that the likes of Go Nagai have received distinguished honors by the French government. You’d be just as surprised, however, to know about the long history of this strong fandom, and how deep it goes.

To understand this, it pays to see how this began well before the terms “anime” and “manga” even entered the public consciousness.

Japonisme: Otaku before Otaku

The term Japonisme (or Japonism in English) was originally coined by an art collector and critic named Philippe Burty in 1874 to refer to woodblock prints and their impact on Impressionism, though the meaning soon extended to include the fascination for (and influence of) Japanese work in general. The phenomenon he described, however, had already been in full swing across France, and across the Western world, for years.

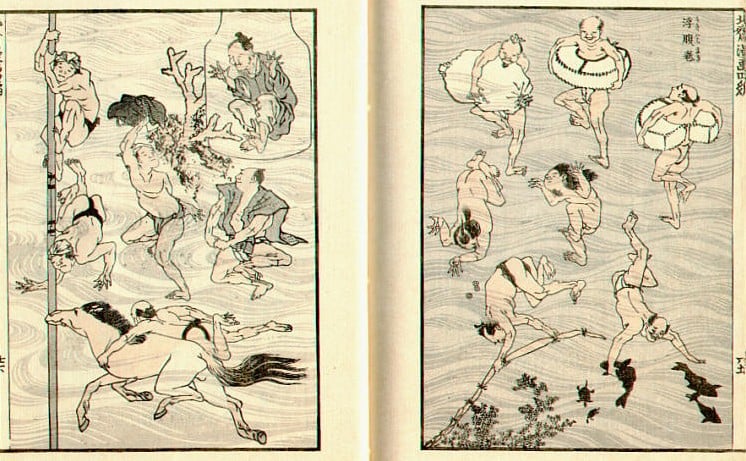

Although porcelain and other Edo Period artifacts found their way into Europe over the centuries, it wasn’t until the opening of Japan in the 1850s that the French infatuation with the island nation’s culture truly began. Indeed, even before a pavilion dedicated to Japan was added to the 1867 World’s Fair in Paris, painter Félix Bracquemond notably became among the first foreigners to come across Hokusai’s work in 1856. From then on, ukiyo-e woodblock prints and other pieces of art became increasingly popular. Shops selling items from the Land of the Rising Sun began popping up even along the fashionable Rue de Rivoli, while articles discussing Japanese aesthetics and culture filled the magazines of the day.

More than exoticism or differing from Victorian norms, however, Japonisme would leave a significant impact on Western, and especially French, artists. Claude Monet, for instance, incorporated many Japanese elements into his work, to the point of representing kimonos and an authentic water garden. Alphonse Mucha, the famed Czech artist who lived in late-19th Century Paris, was very much influenced by ukiyo-e prints, which can be seen in many of his pieces that have come to be associated with Art Noveau and would in time help shape modern manga art.

While this trend eventually ran its course by around the early 20th Century, though not before impacting the likes of Vincent Van Gogh and Gustav Klimt, the notion of French otaku, even before that term would come into existence, had been born. This would help set a precedent for generations to come.

Renaissance: The First French Otaku

The modern history of French otaku arguably begins in earnest around the early 1980s. French producer Jean Chalopin, seeing the then-budding appearance of Japanese anime on Western European television, approached TMS Entertainment for a collaboration with his company, DIC Audiovisuel, which resulted in a sci-fi reimagining of the Odyssey known as Ulysses 31 (1981). This proved to only be the beginning.

Recorded footage, showing the English intro to Ulysses 31. Even for its time, the blend of French and Japanese styles is remarkably harmonious, foreshadowing later works. Circa 1981. (Source: YouTube)

Within the next few years, more Franco-Japanese productions (with DIC working with the likes of Studio Pierrot) were released, notably including shows like The Mysterious Cities of Gold (1982) and Jayce and the Wheeled Warriors (1985). At the same time, works by Nippon Animation were being aired, including anime such as Heidi, A Girl of the Alps (1974) and Future Boy Conan (1978). Granted, the dubs of the time notoriously tended to be heavily edited and inconsistent, if not hilariously bad. Nonetheless, much like their forefathers over a century earlier, French youths were becoming fascinated by Japanese art. Indeed, such was the growing ubiquity of anime that there was even a nationally renowned kids’ TV show, Club Dorothée (1987-97), that was very much a celebration of it. Coincidentally, the program also played a part in further popularizing anime by spotlighting the likes of Dragon Ball (1985) and City Hunter (1987-91), the latter known fondly as Nicky Larson due to the localization.

Then, came the French release of the Akira manga in 1990, followed by the theatrical version a year later, further fueling the growth of the French fandom. The Hokuto no Ken franchise, known in France as Ken le Survivant, and Saint Seiya (1986-89) would soon become household brands, becoming alongside the Dragon Ball saga what Voltes V is to Filipinos or Mazinger Z is to Spaniards.

Archival footage of a Club Dorothée musical number, showing just how popular City Hunter (as Nicky Larson) became in France, thanks to the show. Circa 1990.

Unfortunately, it was also around the late 1980s and early 1990s that, mirroring the panic around video game violence in the United States, the growing presence of Japanese culture attracted the ire of moral guardians. Whether the people involved were conservative or socialist, their spiels denouncing anime and manga in particular as undesirable, if not dangerous, seemed to dominate the public consciousness, further made worse by fearmongering over more explicit content like hentai. These would contribute to the emboldening of the Comité de Surveillance Audiovisuel by 1996, in a manner not too dissimilar to the Comics Code Authority in 1950s America. Combined with legislation meant to promote homegrown works over imported shows and the ignoble end of Club Dorothée in 1997, it seemed like the French otaku scene was on the brink of destruction.

Though, as the old saying goes, it wasn’t over just yet.

Nouvelle Japonisme: Full Circle

Despite the moral panic and fearmongering, the influence of Japanese works couldn’t be erased. Even as Club Dorothée came to a close, the producers of the show managed to establish a TV channel dedicated to anime, which came to be known as Mangas, in 1998. Around the same time, publications began lavishing critical praise no films like Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade (1999) and Studio Ghibli’s Princess Mononoke (1997), with more explicit content even gaining proper localization. This isn’t to ignore how Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence (2004) became the first animated finalist at the Cannes Film Festival. These would go far in helping to legitimize and solidify the country’s otaku culture, especially as the first generation of fans grew up and spread it further in the public eye.

Much the same could be said with manga. According to Cécile Sakai, director of the French Research Institute on Japan, major publishers like Glénat Editions SA began translating whole series by important mangaka en masse in the 1990s; though usually involving 80-90 volumes at a time, these would have also included works like the historically-themed Jeanne (1995-96) by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko of Mobile Suit Gundam fame. Over the 2000s, that growth skyrocketed, and never really stopped. By 2013, it even overtook homegrown bandes dessinées, a feat that not even Anglophone comics could pull off. Such is the impact that there’s a growing trend for French authors to create manga-inspired “Manfra” and collaborate with mangaka to create hybrid nouvelle manga.

RebelTaxi’s review of Wakfu, a solid example of just how far the blending of Japanese and French elements has come. Circa 2019. (Source: YouTube)

It doesn’t seem so surprising, then, why France is seen as the second largest manga market outside Japan itself. Or why there’s a popular live-action City Hunter movie, titled Nicky Larson et le parfum de Cupidon (2018). If anything, it seems like the country’s otaku and artists have all but created a new Japonisme. Though, compared to the 19th Century, this rendition is becoming so ingrained into the cultural milieu that no amount of fear or censorship can stifle it.

So should you ever be in that corner of the world, you’d find something that even Monet would admire.