Anyone with even a passing knowledge of Japanese culture is bound to have come across the many giant robots that show up seemingly everywhere in anime and manga. So many, indeed, that it’s rather easy to feel lost, if not overwhelmed, by the sheer volume alone. That’s where this beginner’s guide comes in. Whether you’re a newcomer or a long-time fan looking for something new, it never hurts to have a helpful map with which to traverse the vast landscape that is Mecha.

“Mecha” in this case is a Japanese term (ultimately derived from the English word “mechanical”) that mainly refers to large, piloted robots. While the concept in itself isn’t exclusive to Japan, as works like the American Battletech franchise or the upcoming German-Polish game Iron Harvest attest, the myriad forms it’s taken and its assimilation into the cultural consciousness are undoubtedly unique. To understand why requires going back in time.

A Historical Precedent

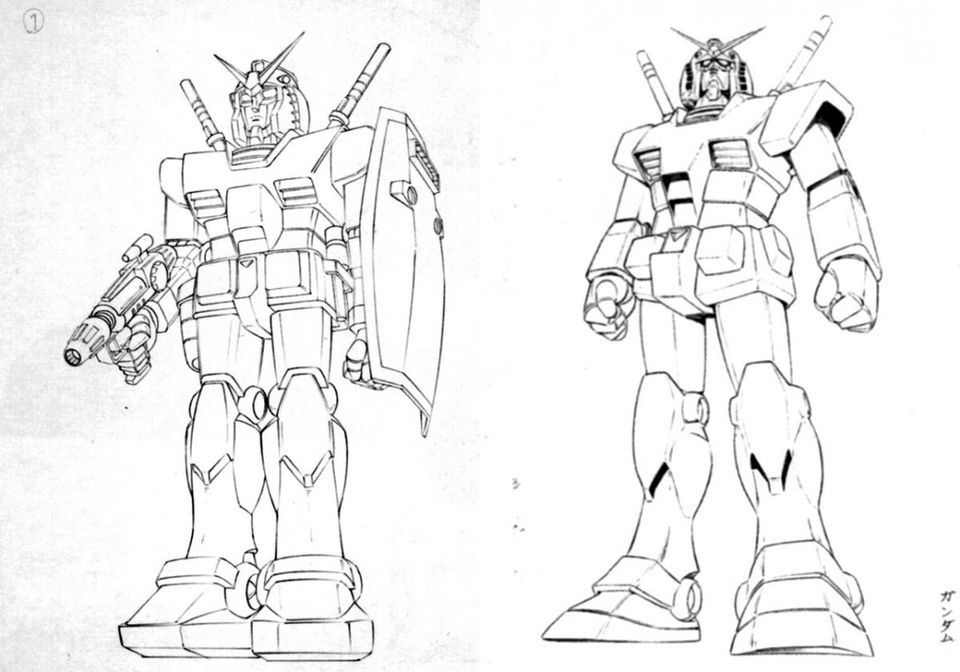

While incredibly varied across genres and works, whether it’s the classic “V-fin” on just about every Gundam or the armor on the biomechanical Eva units, there’s a recurring trend in Mecha to not only look humanoid but also have some element hearkening back to the samurai. According to Ollie Barder (of Mecha Damashii fame) in a Forbes piece, much of this could be traced back to Japan’s history.

The experience of the samurai contrasted sharply with their counterparts in Europe. The knights of yore, with their swords, shields, and stallions, are almost always associated in the West with medieval warfare. Though the code of chivalry would endure, as would a number of knightly orders and titles, the advent of firearms and other trends rendered them obsolete. By contrast, the samurai were not only keener to incorporate aspects like guns into their repertoire, but they were also largely shielded from the technological changes going on among Europeans. As a result, while no longer active on the battlefield, they (along with bushido) would remain a remarkably consistent presence up until 1877. Thus, the samurai managed to endure all the way to the Meiji Restoration and the onset of Japan’s industrial revolution.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vA419L-i-C0

Opening clip from the original Tetsujin 28-go, the first Mecha to gain significant popularity in Japan, then later in America as Gigantor. Circa 1963. (Source: YouTube)

As Barder speculates, this would play a major role in Mecha’s emergence and popularity among the Japanese in the aftermath of World War II. This, however, goes beyond pioneering designers like Kunio Okawara taking direct inspiration from samurai armor or sponsors hoping to sell merchandise to postwar children. Not only were cultural memories of those bygone figures still fresh in the public consciousness, but the historical links to their country’s modernization meant that there was a stronger resonance with audiences. Mirroring bushido and traditional affinities with inanimate objects ensured that fans would identify with the characters piloting those robots, as if they were an extension of themselves (be it Amuro Ray or Shinji Ikari), and certainly added to the appeal.

In other words, Mecha came to be seen as an industrialized reimagining of the samurai. Something that remains true to this day, in all their myriad manifestations.

Manifestations that, whether it’s an anime, manga, film, or video game, generally fall under two categories: “Super Robots” and “Real Robots.”

Super Robots

The proverbial “granddaddy” of them all, Super Robots were among the very first Mecha to be made, beginning with the 1956 manga and later anime franchise Tetsujin 28-go. Over the years, they’ve been popularized, commercialized, deconstructed, and reconstructed several times over, running the gamut from science fiction to fantasy and even comedy.

Although the details vary wildly, you’re bound to find a number of recurring constants in the subgenre. For starters, the focus tends to be on Mecha as robotic superheroes if not demigods. The pilots usually serve as an audience surrogate, who might even call out their attacks to keep the viewer in the loop. Such productions can, especially in older works, be very episodic, wherein the protagonists fight the monster of the week sent by the resident alien overlord or mad scientist. More often than not, the power of friendship and love can save the day.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WLFJhpVdkf0

Snippet from Mobile Fighter G Gundam, showing only a taste of the over the top hijinks from both the characters and Gundams. Circa 1994. (Source: Youtube)

The Super Robots themselves, meanwhile, tend to be very colorful and grandiose in appearance, and may also be sentient themselves. They have a habit of being absurdly powerful and are often pitted against insurmountable odds. Suffice to say, the subgenre doesn’t aim for realism or moral ambiguity, though exceptions like Evangelion exist.

Given the sheer number of works, here’s but a taste of what this subgenre has to offer:

- Tetsujin 28-go/Gigantor (TCJ/Eiken; 1963-66)

- Mazinger Z (Toei; 1972-74)

- Getter Robo (Toei; 1974-75)

- Robot Romance Trilogy (Sunrise-Toei; 1976-79)

- Gunbuster (Gainax; 1988-89)

- Mobile Fighter G Gundam (Sunrise; 1994-95)

- Neon Genesis Evangelion (Gainax; 1995-96; Rebuild series 2007 onwards)

- The Vision of Escaflowne (Sunrise; 1996)

- The Big O (Sunrise; 1999-2000, 2003)

- RahXephon (Bones; 2002)

- Tengen Toppa Gurren Lagann (Gainax; 2007)

Real Robots

The Real Robot subgenre is something of a mirror image of the Super Robots subgenre. Indeed, it began as an outright rebuttal to Super Robots. Among the first of the Real Robots was Yoshiyuki Tomino’s Mobile Suit Gundam in 1979 and Shoji Kawamori’s Macross in 1982. Since then, however, they’ve proliferated to the point of rivaling their more established counterparts, covering everything from military science-fiction to slice-of-life stories.

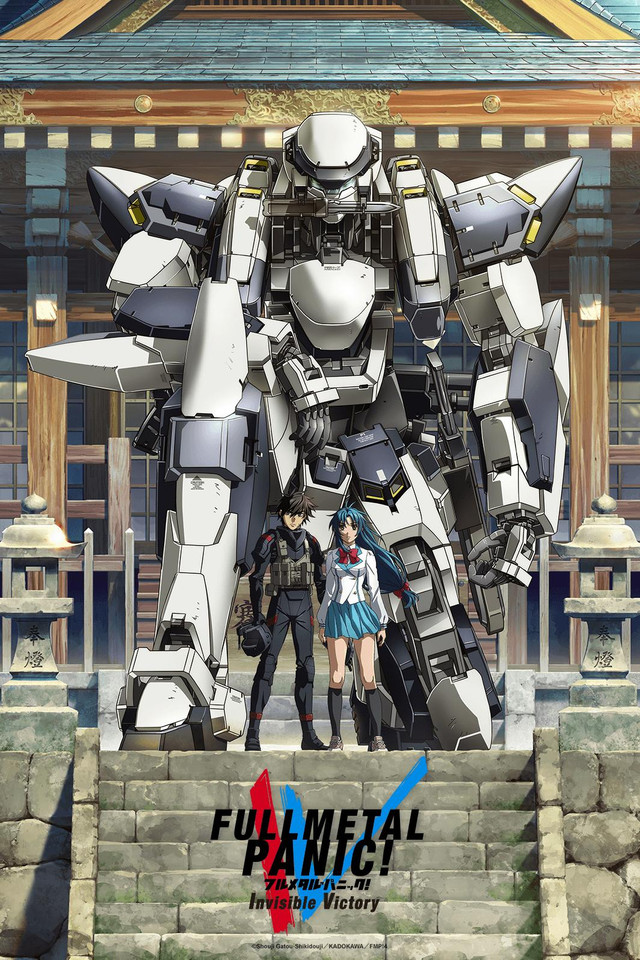

As the name implies, there’s a stronger emphasis on realism and generally grounded motifs. Mecha, in this case, are shown more as industrial machines, which are typically mass-produced as weapons of war, rather than rare superpowered mechanical marvels. The characters in such works, whether it’s the pilots or the ones pulling the strings, tend to be more complex and conflicted. The wider plot and setting, meanwhile, is likely to have at least some degree of moral ambiguity, where the line between good and evil isn’t always so clear-cut. In addition, though determination or love could potentially save the day, the horrors and costs of war aren’t forgotten.

Snippet from the 1995 film Macross Plus, showcasing the legendary “Itano circus/Macross missile massacre” the series pioneered. Circa 2009.

While Real Robots can range from relatively disposable tanks-with-limbs to powerful “Super Prototypes” capable of taking down whole divisions, they all tend to be less fantastical in appearance. Instead, they sport muted colors, conventional aesthetics, and at least a superficial consideration for things like logistics, firepower, and ammunition. This isn’t to say that they don’t stand out or that there’s no overlap with Super Robots, as works like Code Geass can attest. More often than not, the mechanical intricacy of something like the GP-01 Zephyranthes from Mobile Suit Gundam 0083: Stardust Memory can be as mesmerizing as the sleek exterior.

Here’s a sample of some of the most notable works in this subgenre:

- Mobile Suit Gundam (Sunrise; 1979)

- Super Dimension Fortress Macross (Studio Nue-Tatsunoko; 1982-83)

- Armored Trooper VOTOMS (Sunrise; 1983)

- Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam (Sunrise; 1985-86)

- The Five Star Stories (Sunrise; 1989; ongoing manga)

- Mobile Police Patlabor (Sunrise; 1989-90)

- Full Metal Panic! The Second Raid (Kyoto Animation; 2005)

- Code Geass: Lelouch of the Rebellion (Sunrise; 2006-08)

- Aldnoah.Zero (A1 Pictures; 2014)

- Knights of Sidonia (Polygon Pictures; 2014)

- Mobile Suit Gundam Thunderbolt (Sunrise; 2016-17; ongoing manga)

International Legacy

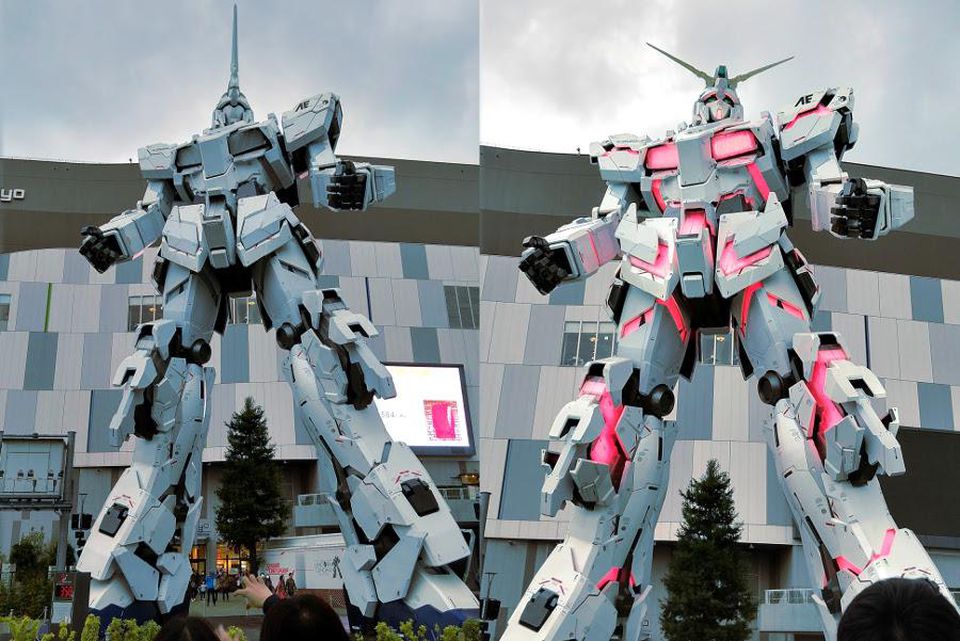

You wouldn’t have to go far to see the impact of Mecha, whatever forms they take, in the wider culture. In Japan particularly, they’ve become so popular and ingrained that they’re found everywhere. Whether it’s a life-sized Gundam in Odaiba, shaving commercials featuring the cast from Evangelion, the existence of Super Robot Wars or the countless references in various media, it seems all but a given that they won’t be fading from the public eye anytime soon.

Their appeal also transcends borders. According to website TitleMax, for instance, Gundam is one of the top 25 media franchises of all time, with a worldwide revenue of around USD 26.46 billion as of 2018, much of it through merchandise like Gunpla. Meanwhile, shows like Mazinger Z and Voltes V have gained cult followings in countries as varied as Spain and the Philippines, which in turn have helped cultivate fans of Japanese culture in those places.

Even Western works have increasingly been taking notes. The aforementioned Battletech in particular, is known to have taken inspiration from shows like Fang of the Sun Dougram. Then you have a film like Pacific Rim, which goes even further in being a live-action Super Robot homage. If anything, such cases highlight not only cultural exchange in action, but also the nigh-universal appeal of Mecha.

Single-player trailer for Titanfall 2, which like its predecessor weds Western and Japanese Mecha elements into a distinct blend. Circa 2016. (Source: YouTube)

Of course, this is just a taste of the vast frontier Mecha has to offer. All that’s left now is to charge into the fray.