I talked last time about the invisible lines drawn between the three social groups in a Japanese school or organization, senpai (upperclassmen, seniors), persons who are on the same level as you seniority- or age-wise, and kohai (lowerclassmen, juniors), three concepts which can be tricky for non-Japanese to grasp. Social rules require that you speak with (slightly) polite language when addressing a senpai, whereas you can speak informally with people on the same or lower level. While we use the word “friend” in a wide range of situations in English, the corresponding Japanese word tomodachi is generally reserved for people who are the same age as you, while the terms senpai/kohai are used to refer to older/younger friends, even if you hang out with them all the time. Since the bursting of Japan’s bubble economy in 1989, the vaunted lifetime employment system has all but disappeared, and it’s quite common for a person to change jobs 2-3 times in his adult life. This causes a bit of a challenge to the Japanese system of seniority — if a man in his 50s goes to work at a company with a boss in his 20s, which is the senior? The answer is, the employee with more seniority in the new company, which means that the tidy system of politeness based on age starts to look pretty strange in the Japan of today. It’s an interesting example of social forces bringing about changes in language, right before our eyes.

Foreigners in Japan unconsciously pick up on the senior/junior system, too, and when I used to meet new English teachers while drinking at the local bar “AIUEO” (what a great name), we’d ask each other how long we’d been in Japan to establish the proper invisible order of “gaijin seniority.” Of course, to be a senpai to someone doesn’t just mean a one-way ticket to getting respect from them. You’ve got to earn it by providing help and guidance to your kohai, doing things like picking up the tab at restaurants and generally assisting them in their jobs. Just as various kind souls helped me get my “Japan legs” when I first arrived here, it was my responsibility to help out newer foreign teachers I encountered, and I did my best to fulfill this responsibility. In our town there’s a guy who had everyone beat when it came to gaijin seniority, an American who came to Japan during the Vietnam War and stayed ever since. He writes articles for the Japanese newspaper about how the country has changed since he arrived, and has a kind of mythical status a “First Foreigner” in our prefecture.

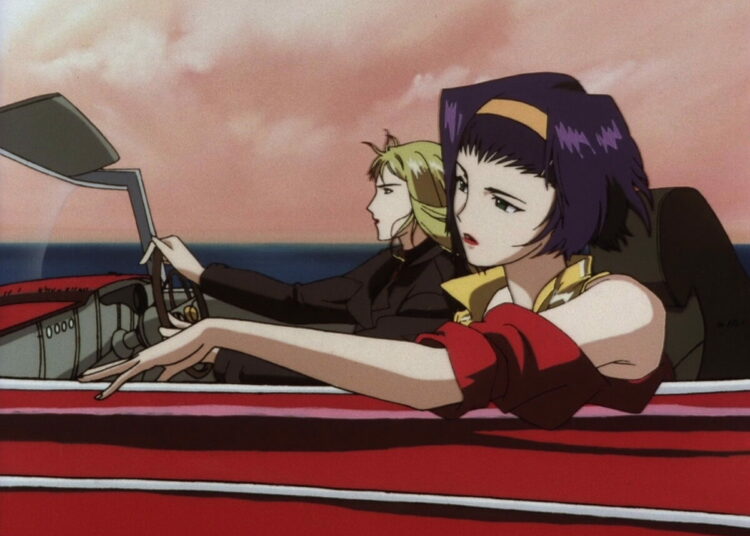

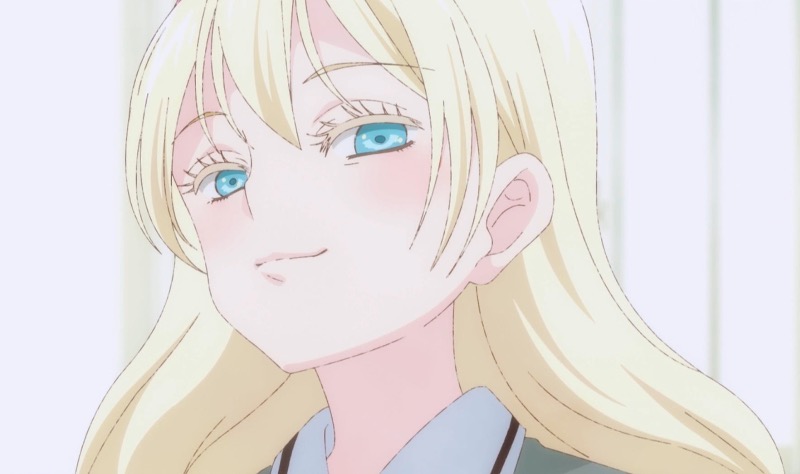

The national past time of the Japanese isn’t singing karaoke, or writing haiku poems, or taking in the beauty of Mt. Fuji while the cherry blossoms fall all around. For many, it’s playing pachinko, essentially a vertically oriented pinball machine which you shoot metal balls into, hoping that enough balls happen to fall into one of the special holes in the machine so that more balls are released, eventually giving you more than you started out with. Although generally viewed as a hobby of middle-aged men, many women play the game, too, and since women have more money (they traditionally control the family finances in Japan), pachinko parlor operators are scrambling to attract this more profitable market segment. The newest theme in pachinko is machines that feature The Rose of Versailles, an anime series about the French Revolution that millions of females in Japan have fallen in love with over the last four decades. While you play, various scenes from the show are displayed on the LCD screen, with updated animation so it looks really nice. If you play well, you get to view special scenes with Oscar and young Marie Antoinette. Other recent pachinko trends include machines centered around enka singer Hibari Misora, and good old Yon-sama, aka South Korean heart-throb Bae Yong Joon, much beloved by middle-aged Japanese women.