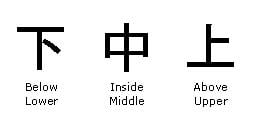

The Japanese writing system is based on kanji, the pictographs evolved by the Chinese starting around 2500 B.C., and China serves a similar role to Asia as Rome does in the West as the primary basis of writing and culture. Although learning to read kanji is a challenge for Westerners, it’s actually quite a logical when you get used to it. First, the simplest characters are stylized representations of everyday objects, like mountain (yama) or rice field (tanbo), both of which look so much like what they mean you might be able to guess them just by looking. One of the most famous kanji characters in the West is naka (also read chu), which means “inside” or “middle” and can be seen on the costume of the Greatest American Hero and in the film Red Dragon, as well as in the name for China itself (“the country at the center of the world”). Kanji is composed of “radicals,” essentially characters within characters which help to organize things. For example, the kanji for “to say” (iu) looks like a stack of books, and many kanji with similar cognative meanings, such as to read (yomu) or language (go) feature this character on the left half. In the Chinese speaking world there are two standards for characters, Traditional (used in Taiwan and Hong Kong) and Simplified (used in mainland China, Singapore and Malaysia). Since kanji have been used in Japan since the 6th century B.C., Japan uses the former, with the result being that I can probably read a menu with little problem in Hong Kong (although I couldn’t prounce anything correctly), but I’d be quite lost in China proper.

What Anime Raised You? J-List Customers of Culture Respond!

One reason I love social media like X, Bluesky, and Facebook is that I can post questions to my followers...