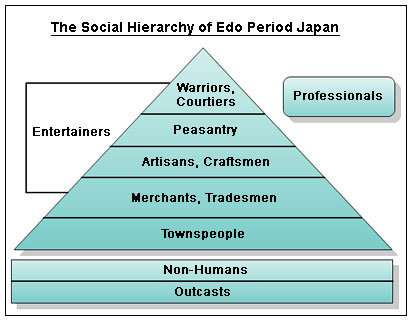

I caught an article on the New York Times website the other day about Japan’s little secret, the class of “untouchables” that lived at the bottom of Japanese society for centuries. Known as burakumin, which oddly enough can be translated as “village people,” they historically did jobs such as tanning, undertaking and the slaughtering of animals, considered “unclean” in both Buddhism and Shinto. While there had been a lower class of people serving this role from antiquity, burakumin didn’t become defined as a specific class until Toyotomi Hideyoshi came along. He was a peasant who managed to work his way up in the ranks until he was the most powerful man in Japan, shogun in all but name, and one of the first things he did was change the rules so that no one else could follow in his footsteps. He created the four-caste system (called shino-kosho), which re-aligned society into four groups, with samurai warriors at the top, followed by the peasants who grew the rice everyone ate, the artisans who made swords and other products, and finally the merchants. The fact that the burakumin aren’t officially included in any of these castes highlights their status as “non-humans” — they weren’t even worthy of mention. The official status of the burakumin continued until 1871 when they were freed, but discrimination continues to this day. The extent of this discrimination and what form it takes is difficult for me to actually report on — the issue of burakumin is so taboo that it’s almost impossible to get anyone to talk about it. I can say that the Japanese are extremely conscious of how terrible it is to treat a person differently just because of what job his great-great-grandfather happened to do, and it’s illegal to consider burakumin status in employment or other areas of society. I’ve never heard the subject of someone’s burakumin history brought up in any form, and the fact that I’ve lived here for 18 years without, say, hearing a slang word referring to the group says to me that Japan has done a pretty good job of expunging this aspect of discrimination from its society.

Social organization of the Edo Period