Last year, Capcom’s President Haruhiro Tsujimoto voiced his opinion that video games are “too cheap.” Tsujimoto’s stance comes from the belief that development costs have increased, but game prices haven’t risen to match. Is there any truth to this? Well, yes and no. I have been a gamer through the ages of bulky plastic cartridges, jewel case disks, and the infamous Horse Armor DLC. Gaming has always been a relatively expensive hobby.

“Development costs are about 100 times higher than during the Famicom era, but software prices have not gone up that much. There is also a need to raise wages. Considering the fact that wages are rising in the industry as a whole, I think raising unit prices is a healthy option for business.”

Those sentences are carefully worded. During the Famicom era of the ’80s, games didn’t have voice or motion-captured actors, a big slice of the cost for even a single-language game. Developers now work with more complex systems, and detailed graphics, like in Final Fantasy XVI, require big teams to produce a sense of scale that was unheard of before. Then consider music, sound effects, and the massive marketing budgets a triple-A game needs to make a splash.

The Costs of Capcom’s Production

But here’s the catch: we don’t need games with large worlds, fancy music, expensive voice actors, and graphics so detailed we can see the character’s facial pores. Capcom has been making triple-A titles for a while but has also made smaller titles like Monster Hunter Stories 2 and their classic game collections. The real issue at play is production costs. Are they too high for triple-A games? Ironically, the gaming industry seems to be thriving, reaching an astounding estimated worth of $97 billion in the United States alone.

Inflation has risen worldwide since the global market stabilized from the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, according to Capcom’s most recent fiscal report, the company made $760 million in revenue. In 2022, Capcom released only three products: Capcom Arcade 2nd Stadium, Capcom Fighting Collection, and the effectively dead Resident Evil Re:Verse. For them to make so much revenue in what is ostensibly an “off year” is incredible. So, how’d they do it?

Capcom’s “Digital Revenue” Smokescreen

Simple: digital transactions. Pay close attention! If we look at the same report, it gives us a clear picture of where Capcom is making the most money. That is, without a doubt, their game sector. The report shows that packaged game sales account for 36% of their total revenue in that sector. Meanwhile, digital content accounted for the rest. Are you paying attention? I didn’t say “digital game sales.” Why? Because they don’t either. Capcom, along with many other game companies, shove sales of all digital content under one umbrella. Including DLC. Including licensing costs to subscription services like Game Pass. And then other micro transactions.

Capcom released data in 2023 showing that digital game sales (they used those exact words this time) accounted for a staggering 89.4% of their sales for the 2023 Fiscal Year. The future of physical games looks bleak. At least until you remember some essential information. First, Capcom had only two physical releases in FY 2023: Capcom Fighting Collection and Resident Evil 4. The former is a niche title, and the latter launched with only a week of the fiscal year remaining. They also ran a publisher sale on all digital storefronts for almost all of March. In context, it’s obvious why digital sales dwarfed physical sales.

This is only part of what has now become an industry-wide narrative push to force physical games off the market and secure the bigger cut digital provide. This brings us back to Capcom’s comment about games being “too cheap.” Let me get my tinfoil hat for this. The dirty truth of it is that Capcom wants more money. The company achieved a sixth consecutive year of record profits in FY 2023. And in the FY 2021 release, they mentioned their end goal was for their profit margins to come 100% from digital sources.

The Reality of Internal Data

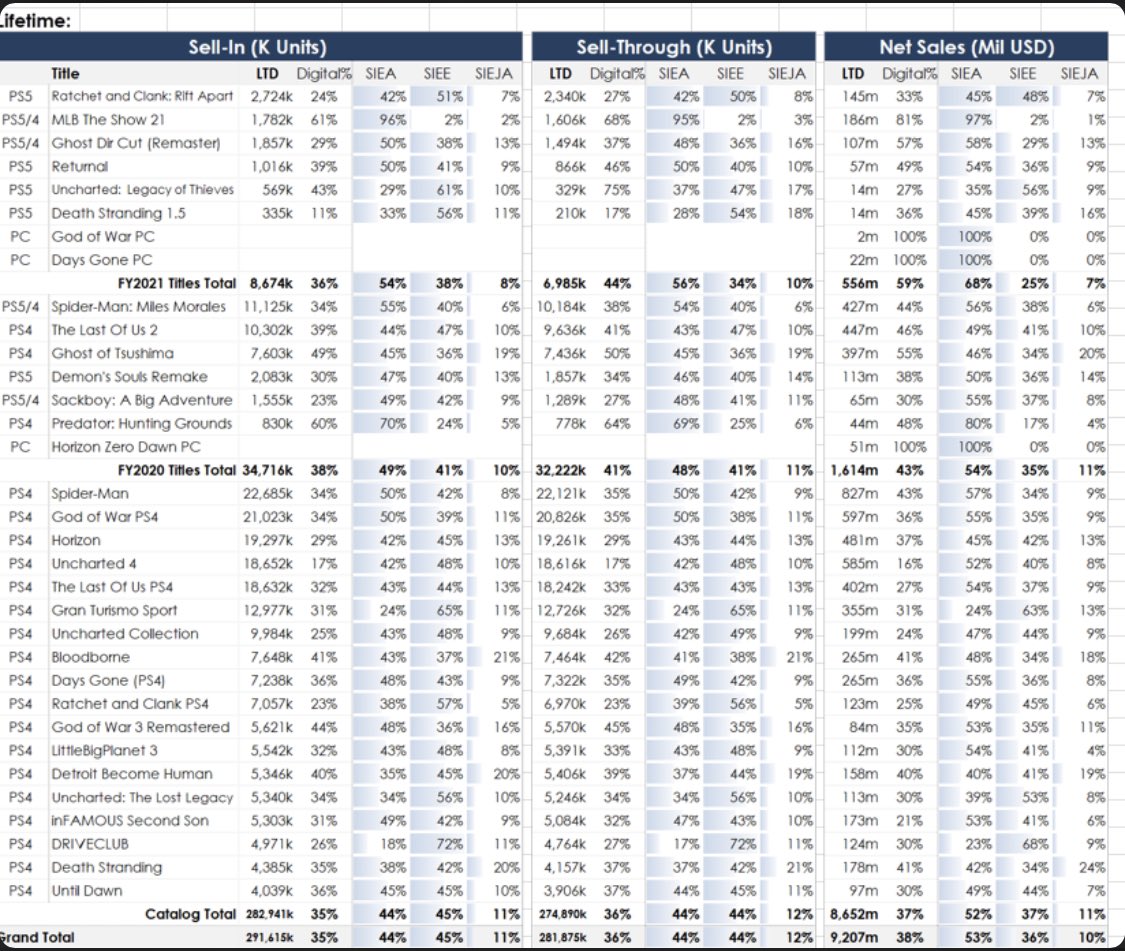

Sony’s internal documents, leaked through the massive Insomniac Games leak, provide the best information from the best source possible. The table below comes from there. We’ll not link directly to it, as it includes identifying information of Sony employees. It also includes sales numbers for several of Sony’s biggest games. But I want to draw special attention to the column marked “sell-through.” The term “sell-through” is when a game is sold from a retailer to the end consumer, and those are the metrics that matter most. Next to that column, you’ll see the percentage of physical copies from those sales.

Of the 30+ titles listed, only three sold more units in the digital space. Other highlights include the long-neglected Bloodborne outselling several titles and Japan’s apparent love of Ghost of Tsushima, the Western-developed samurai epic. As neat as those details are, the most significant data is the physical sell-through. This data disproved the narrative that “physical is dying,” which has been pushed for the past year or two. But the question remains — why is that narrative put forth? To cut right to the heart of it, companies get more money from digital purchases. Period. They don’t have the overhead costs of manufacturing, distribution, and the retailers’ cut. It’s reasonable to extrapolate that data out to third-party developers like Capcom.

Aren’t Games Cheaper Now Than in the ’90s?

It’s “technically true”, even without adjusting for inflation, that games cost more in the ’90s. Occasionally. Look at the scan of an old Best Buy ad below to see what I mean. But why were they so expensive? Production costs of the games themselves were a huge reason. Games from this era all used proprietary formats, and making them was not cheap. They all had circuit boards, some had battery saves, and a select few even had an additional graphics chip inside the cartridge, like Star Fox. Then, there are licensing fees to the console makers, manual costs, plastic molds, etc. Once CDs dominated the market, production costs sank and prices dropped too. This is evident with prices between the N64 and PS1.

CDs were far better than the N64 cartridge, which held 256MB, while all PS1 disks held 600MB. This is doubtless why the N64 had such a small library and struggled with ports of PS1 games like Resident Evil 2. You can still see the ripples of this in the current generation with the Switch. The smallest and cheapest Switch cartridge has a measly 1GB of data. As such, many AAA companies opt for cost-cutting measures on physical copies of Switch ports, like making consumers download the rest of the game.

What’s the Verdict?

Games aren’t “too cheap.” The smoking gun is Capcom’s financials and their transition to digital-only. That’s where the data points. If production costs are so high, it’s probably time to dial them back a bit rather than trying to force the cost back onto the consumer. I know Capcom has a duty to its shareholders to make more money. However, the infinite growth model is not sustainable. I have a soft spot for Capcom and their games, but these statements worry me. Luckily, Japan saves the day yet again, as physical sales in Japan are big. Most big games, even if digital-only here in the west, have complete physical copies in Japan, even with English options. Examples include Yakuza Gaiden, River City Girls, and Baldur’s Gate 3.

We stock some of these, such as the incredible Hatsune Miku rhythm game Project DIVA Mega 39’s. I recommend the physical version, as the game is massive and will take up a ton of space on your SD card.