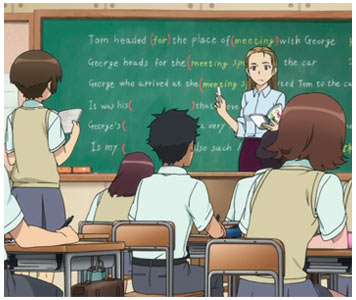

One of the good things about teaching ESL in Japan was learning my own language. Languages are based on rules which are internalized by speakers of that language, and part of the reason why New Jersey English or Osaka Japanese sounds odd to people who aren’t from those places is, speakers from those areas are using a slightly different set of internal rules. Although we all learn some grammar in school (does everyone remember creating sentence diagrams?), the only way to really learn something is to teach it, to stand in the middle of a classroom with students who are struggling for answers. After letting my students down by saying “uh, sure, I guess that sounds right” a few times (Japanese students hate teachers who do that), I buckled down and learned how to teach grammar. Did you know the difference between “the” (rhyming with “three”) and “the” (rhyming with “uh”)? The first is used before words starting with vowels (“thee end”) and the latter before all other words (“thuh dog”), although it was news to me at the time. What do you do when a student asks why you have to say “a piece of chalk” when it’s clearly something you could count like a pen or pencil. Or why pants and glasses are “pairs” when you can’t separate them? Or why can we count fish individually, but the meat of a fish is non-count? Or why words like “sky” and “sea” appear plural sometimes (e.g. “the Friendly Skies” or “the seven seas”)? One rule of English that threw me at the time was the long list of words with different intonations depending on whether they’re being used as nouns or verbs (e.g. research the research, permit the fishing permit, present a present to someone, or rebel against the rebel base). Surprisingly, living in a foreign country has put me more in touch with my native language.

If you want to learn something really well, teach it.