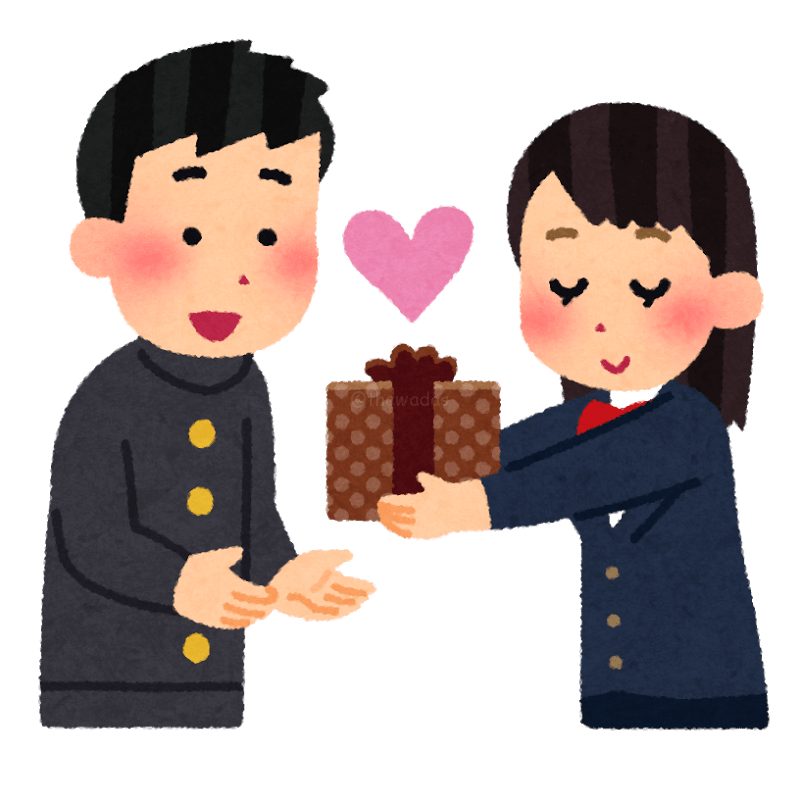

You probably know that they do Valentine’s Day a little differently in Japan than in the West. Here, Feb. 14th is a day for women and girls to give chocolate to men and boys, and all throughout Japan, millions of fathers, husbands, boyfriends and would-be-boyfriends look forward to scoring some chocolatey goodness. In Japan, you never receive a gift without giving one in return, called o-kaeshi, and March 14 has been designated as “White Day” when males give something back to females who gave them chocolate the month before. (In South Korea they’ve taken this a step further with “Black Day” on April 14th, a day when single males who didn’t receive chocolate bitterly eat black noodles, wallowing in their single-ness.) My son and I were looking forward to some delicious handmade chocolate today but we’re out of luck, as both my wife and daughter are bedridden with this year’s bout of influenza that’s going around. Zan-nen! (ZAHN-nehn, meaning “what a bummer!”)

In case you’d like to know the history of Valentine’s Day in Japan, I’ll tell you. The first Valentine’s Day advertisement in Japan appeared in Showa 11 (1936), when a chocolate shop in Kobe called Morozoff promoted its wares as being perfect for lovers to enjoy together. World War II got in the way, and it wasn’t until after the war that people could think about anything as frivolous as chocolate. In 1958, the manager of the Isetan department store in Shinjuku got the idea of having a Western-style Valentine’s Day chocolate sale, but it was a total flop — they sold just five boxes of chocolates! Attempts to raise awareness of the day continued with poor results, but in the 1970s, chocolate maker Morinaga hit on the idea to promote Valentine’s Day as a day for women to give chocolate to boys and confess their love, and the rest is history. Currently, 60% of females in Japan report giving chocolate to someone, which makes for a lot of happy fathers, husbands, boyfriends and would-be-boyfriends.

I’ve talked before about what the Japanese call kokumin-sei (koh-ku-meen- SAY), a kind of “national personality” that’s basically the essence of what makes Koreans so Korean and the French so very French. One of my favorite aspects of the Japanese is their dislike of confrontation and general willingness to get along with each other on a daily basis. By and large, you won’t find yourself being hassled much in Japan, and even some of the scarier people you might encounter, like yakuza in the public bath with their full-body tattoos, are quite polite as long as you’re polite to them. This harmonious attitude extends to the legal system, too, making lawsuits extremely rare. When there’s an automobile accident, for example, the two insurance companies work it out between themselves, weighing the various factors before coming to an agreement on how to divide fault between the two parties, and it’s virtually unheard of to have issues decided in a courtroom. There are quite a few identifiable mechanisms that help the Japanese get through the day harmoniously, like the mantra sho ga nai” which means it can’t be helped,” and the basic golden rule of society that you should never cause meiwaku (inconvenience) to others. There are some possible theories about why the Japanese are so good at getting along. Perhaps it comes from having to learn to live in a small country with many people around, or maybe it has to do with Japan’s decision to become a peaceful country after their defeat in World War II, or just maybe it’s a by-product of the long period of absolute rule by the Shogunate during the feudal Edo Period. My own theory comes from the ethnic name of the Japanese people, the Yamato, which is also Japan’s first name for its own country, dating back to the 4th Century. The characters literally mean either “Great Peace” or “Great Harmony,” and it seems natural to me that a country with such a name would value getting along with one another in a peaceful way.

Remember that you can get all the great anime, manga, toy/hobby, fashion, and other magazines in Japan sent to you each month, thanks to J-List’s popular Reserve Subscription service. Here’s how it works: for most items, you have the option of either paying month-to-month or paying for a full year in advance. If you choose the former option, we’ll reserve the current issue of the magazine(s) you want each month, charging them to a credit card on file if like, or else by check/money order or Paypal. The amount charged is the same every month, e.g. $8.50 each issue of Newtype Japan, plus the shipping. If you want to choose the annual payment option, you can pay for all the issues and SAL shipping together and get a discount. The annual option is great for anyone who wants to pre-pay for the issues (including libraries and universities who use our services), and our convenient month-to-month option is recommended for anyone who wants the flexibility to stop or change subscriptions at any time.