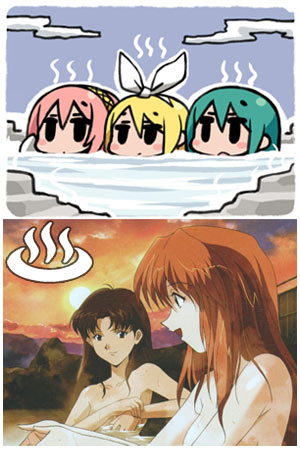

Like many people in Japan, I am a 風呂人 furo-bito, or a person who likes taking baths in natural hot springs (onsen in Japanese, pronounced own-sen), and wherever I drive I’ve got a bath kit with towel, razor and toothbrush in the car with me. Just as saunas are important to people in Nordic countries in Europe, volcanic hot springs are almost a national treasure in Japan, and many existing onsen towns have a history that goes back 1000 years or more. Most hot spring baths have a official-looking sign posted somewhere describing the chemical make-up of the water and affirming that it is a true volcanic hot spring, since some establishments have gotten in trouble buy promoting boiler-heated baths as natural. It’s also common to see signs boasting of all the ailments that will be cured by a sitting in a given bath, including rheumatism, chills, muscle or joint pain, skin problems, cramped shoulders, sleeping disorders, and even anemia. One famous image associated with Japan’s culture of bathing is the “onsen mark,” the official icon used to denote the presence of a public bath on maps.

I’m a big fan of Japan’s bathing culture.