It’s been another unbelievable roller-coaster of a year for all of us a J-List, a time of learning new things and enduring difficulties as we fulfilled our mission of being a bridge of popular culture between Japan and the rest of the world. It was a hard year, a sad “Year of Tears” for anime fans which saw the passing of the voice of Speed Racer, the composer of the Macross “Do You Remember Love?” song, Voltron producer Peter Keefe, famed director Satoshi Kon and the “Great Bird of the Anime Galaxy” himself, Carl Macek. It was a very difficult year personally, too, and I couldn’t sum it up any better than by paraphrasing the opening credits of season 4 of Babylon 5:

“It was the year of rebirth… the year of great sadness… the year of pain… and the year of joy. It was a new age. It was the year…everything changed.”

The Japanese have quite a few superstitions, something I write about frequently in my update emails. Perhaps the most widely believed superstition of them all is that there are certain “unlucky” years in a person’s life, called yakudoshi or Years of Calamity. For a man the unlucky years are age 25, 42 and 61, and for a woman it’s 19, 33 and 37, with the years before and after each yakudoshi year being somewhat unlucky, too. During these years you’re supposed to avoid doing new things like building houses or starting journeys, and perhaps keep bad luck at bay with a traditional omamori good luck charm. I’m 42 years old now, and this has certainly been a hard year for me, although the good news is my bad luck year is at an end — or will be in February of 2011, an odd holdover from when Japan followed the Chinese Lunar calendar.

Dec 31st is an important day in Japan, spent doing last minute oh-souji or “big cleaning,” including washing your car so you can start the new year with a clean slate. People eat buckwheat noodles called toshi-koshi soba (lit “Crossing the New Year” noodles) which supposedly help you live longer because the noodles are long (or something like that). The centerpiece to New Year’s Eve is the Kohaku Uta Gassen (Red and White Year-End Song Festival), the 5-hour variety and music show broadcast on NHK here and around the world, now in its 61st year. Virtually all of Japan’s famous singers, comedians and other “talents” appear in the entertainment extravaganza, as the white team (male singers) battle the red team (female singers) to see which side can put on a better show. Anyone who’s anyone will be there, from the popular AKB48 to Johnny’s-kei boy bands like Arashi to seiyu Nana Mizuki and enka greats like Sayuri Ishikawa and Saburo Kitajima. At 11:30 pm, a team of judges and the audience votes to see which group was more talented, and then everyone sings Auld Lang Syne in Japanese, called Hotaru no Hikari or By The Light of the Fireflies. (Incidentally, you can see this year’s Kouhaku songs on iTunes Japan with this link, and purchase them with our iTunes Japan prepaid cards.)

As usual, there’s more to Japan than meets the eye, and the “red and white battle” tradition isn’t simply because red and white are the colors of Japan’s national flag. The origin of “red-white” as a kind of unique Japanese yin-yang started back in the Heian Period (794-1185), during the Genpai War in which the Taira and Minimoto clans fought. The Minamoto clan had red flags as their battle standard while the Taira had white, and these colors became a theme that has continued up to the present. Today red and white are seen at thousands of sports days across Japan, as children are divided into teams of red and white and awarded points on fast they run, and there’s a special kind of red-and-white mochi, too. Red is associated with babies (which are called aka-chan in Japanese, lit. “little red one”) while white with the color of funeral garb, and together the colors celebrate life as a whole. The colors of red-and-white can even be seen on the traditional fukubukuro New Year’s grab bags we have on the site.

At 15 minutes before midnight, the Kouhaku show ends and one of my favorite programs of the year begins. It’s called Yuku Toshi, Kuru Toshi (“Old Year Departing, New Year Arriving”), and NHK sends camera crews to dozens of shrines, temples, churches and mosques all around Japan then shows live images of visitors arriving to make their first prayer for happiness in the New Year, the local equivalent of going to Midnight Mass. The bells in shrines and temples ring out 108 times to purify the 108 temptations that humans are subject to, and presumably to reset the computer on the Island in Lost. Then, without any fanfare or countdown, the clock on NHK’s video feed flashes 0:00, and the new year is here.

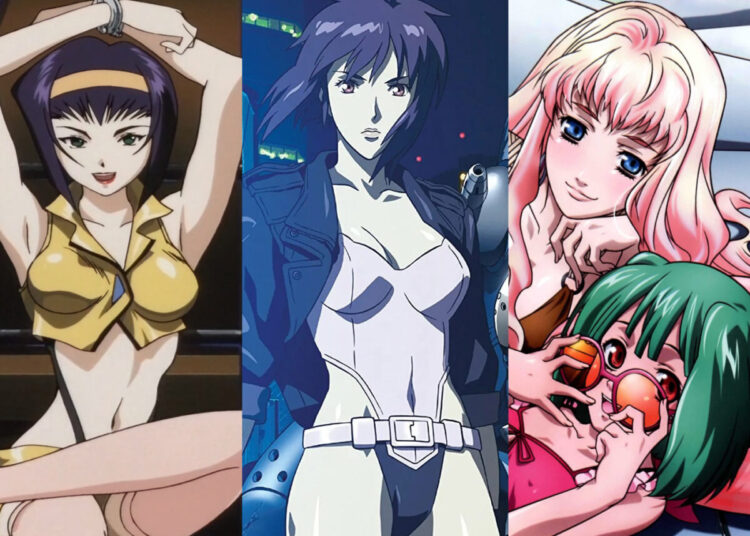

The Kouhaku Song Battle is the show to watch on Dec. 31st.