There are subtle nuances in how we use language, and the speech we choose to use says something about all of us. In English, men and women speak differently in subtle ways, choosing varying words or inflections or coloring their speech differently (e.g. cursing, using feminine-sounding intonation, using less or more slang). In Japanese, the line between male and female speech is much more pronounced, with separate words for the first and second person, e.g. watashi as “I” for girls and the more masculine-sounding boku for boys. There are grammatical “particles” that go on the ends of sentences, too, stressing a statement or asking for agreement from other listeners, and several of these, such as wa (note, わ not は, i.e. the end-of-sentence wa, not the subject-marker wa, or the trendy-word-meaning-harmony wa either for that matter) or ne are generally used by women, or (don’t ask me why) men from the Osaka region of Japan. The big challenge for male learners of Japanese is to find the right balance when speaking, to avoid picking up feminine Japanese (difficult when learning from female teachers/girlfriends/wives), while getting input in “male” Japanese that’s right for your age (picking up slang from junior high school kids isn’t much use when you’re 35).

Last week there was a big demonstration in Tokyo’s Akihabara region, with otakus of every creed, color and cosplay taking to the the streets to demand freedom to pursue their love of anime, manga and the related arts in their chosen homeland. The demonstration was lead by groups such as the Revolutionary Moeist Union — who may or may not have been aware of the great joke they made using the word moe (萌え、mo-EH), roughly translatable as the warm, fuzzy feeling you get when contemplating your favorite anime or video game character — and they were rallying against the recent otaku-unfriendly changes in Akihabara. Tokyo’s plan to turn the area into a hip tourist spot has seen many large retailers moving in, including the mammoth Yodobashi Camera store that opened a few years back, pushing out smaller shops that catered to the “otaku spirit.” Originally known as Tokyo’s “Electric Town,” Akihabara has grown beyond electronics to become the Mecca for everything from manga to anime to maid cafes to, well, mecha, and if there’s a Jerusalem for anime fans, this is it. Indeed, the word “Akiba-kei” (“related to Akihabara”) refers to otaku culture in all its many forms, not to duty-free electronics stores that have been established since the 1960s. The demonstration was mostly for fun, of course, a chance to dress up like your favorite anime character and take part in something spontaneous, but some of the participants really seemed to be getting into it, hiding their faces like PLO guerillas and beating their breasts as they demanded freedom to be otaku in their chosen part of Tokyo.

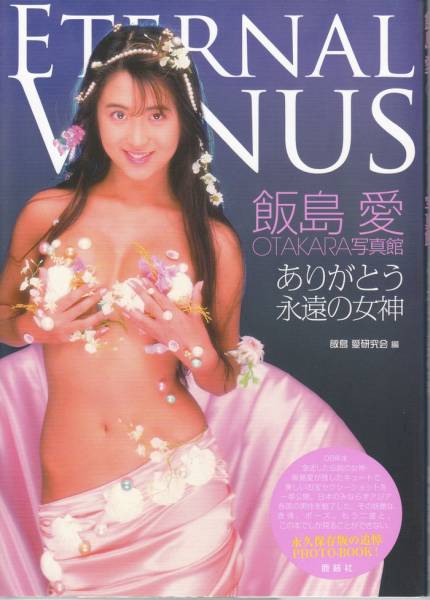

Japan is not happy, it seems, if it’s not constantly presenting foreign visitors with conflicting images of itself. On the one hand, the country can be considered quite open when it comes to subjects like nudity and sex. Public bathing is still quite common, and while male/female mixed bathing (called konyoku, as in our wacky “mixed bathing” T-shirt) has become somewhat of a rarity — I’ve only managed to find one such bath in all my years of onsen- hopping, and I’m been paying really close attention– getting naked in front of strangers of the same sex is still something Japanese never bat an eye at. Occasional nudity on television is by no means shocking, even during prime time, and late-night television in Japan can still give Benny Hill a run for his money when it wants to. Sex has been expressed in art for centuries, and the subset of ukiyoe known as shunga (“spring pictures”), which included the first “naughty tentacles” depiction, dates back to the Edo Period. On the other hand, Japan can be an extremely conservative place at the same time. The roles between men and women are still trapped in the 1950s in many ways, with some girls ernestly wanting to be nothing more than housewives when they grow up. Alternative lifestyles are generally not shared with others, and although the English word “coming out” exists in Japanese (カミングアウトする), it’s almost unheard of in practice. When my wife and I went to Thailand with some other Japanese tourists, there were many Europeans there, sunbathing with their tops off, but the idea of trying this was positively scandalous to all the Japanese tourists.