In the span of two decades, Makoto Shinkai has emerged as a leading figure in the modern anime industry. With Your Name (2016) alone being the highest-grossing anime ever made, second only to Spirited Away (2001) in Japan, it’s not for nothing that he’s been described as a latter-day Hayao Miyazaki. While he humbly considers it an “overestimation” of his abilities, his particular style has proven to be both a solid constant and rather timeless. His first major work, the OVA Voices of a Distant Star (Hoshi no Koe; 2002), in particular, demonstrates his abilities exceptionally well.

Running at 25 minutes and nominally produced by CoMix Wave Films, the short film was made almost single-handedly by Shinkai himself. As noteworthy as that feat is, the anime’s enduring appeal comes from deep within.

Welcome to the Stars

Voices of a Distant Star starts off in the not too distant future of 2046. Middle-schoolers Mikako Nagamine and Noboru Terao originally planned on entering the same high school together. As the UN Space Army begins mobilizing against the alien Tarsians, however, Mikako finds herself recruited into the war effort as a “Traser” mecha pilot onboard the starship Lysithea. The two friends manage to remain in touch through email, but it takes ever longer to send and receive messages as the UN fleet gets closer to the distant enemy homeworld of Agartha. Back on Earth, all Noboru can do is wait for a note that may never come, uncertain whether his beloved is even alive at all.

At a glance, the premise bears more than a passing semblance to the likes of Joe Halderman’s 1974 novel The Forever War. This may not be coincidental, either. The Tarsians, for instance, are somewhat reminiscent of the Taurans in the book, as is the backstory behind the conflict itself, which could be described as “first contact gone wrong.” More significant, though, would be the use of time dilation. While not the first anime to feature it in any meaningful capacity — that honor belonging to Gunbuster (1988) — the OVA plausibly shows how long it’d take for emails between the couple to pass through the void. Given enough distance, even the speed of light can seem like “20th Century air mail,” as Mikako puts it, or worse, a message in a bottle cast off into the sea. This is reflected in how the two protagonists’ perception is affected. While one character’s arc is largely set in 2047, another jumps forward in successively larger intervals, eventually taking place around 2056.

It’s no coincidence, then, that this underscores the prevailing theme of Voices: distance and communication between people. Shinkai remarked in a Newtype USA interview in 2002 how this was based partially on how cellphones, as seen throughout the anime, were (and still are) commonly used in Japan. This, however, serves more to focus on how something as seemingly mundane as getting in touch with one another can transcend obstacles, whether it be grief from separation or the literal vastness of space. What he called “communication from the heart,” according to a video interview for the DVD release, is given further weight through the personal drama of the protagonists (from their inner monologues to how they try to cope with separation) as well as the increasing urgency of the messages over time.

A video interview with Makoto Shinkai from the original DVD release, showing the background and meaning behind the anime’s creation. Circa 2002. (Source: YouTube)

Even at this early point in the creator’s career, one could already see more than a whiff of what would become his trademark style. A style that permeates the whole anime.

A Labor of Love

From a purely technical standpoint, it deserves stressing how much of a one-man production Voices of a Distant Star truly was. According to Shinkai, memories of watching Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986) and various Dracula movies in middle-school spurred him on to want to make something as amazing as those films. The increasing availability of hardware and software tools by the dawn of the 21st Century, along with the trends of individual creators, reinforced the idea of him doing it himself. It would be an illustration he drew in 2000, however, of a girl holding a phone in a cockpit, that truly set the ball into motion. With little more than a Power Mac G4 and some software (including LightWave and Adobe Photoshop), he managed to do almost everything over the course of seven months, from the visuals to the animation itself. Indeed, among the handful of aspects he didn’t do by himself was the soundtrack, which was done with the help of composer and friend Tenmon. That he even released it in a complete state at all would be a feat in sheer determination, but it’s only the tip of the iceberg.

The visuals alone are a sight for sore eyes. Whether it’s the stellar vistas around the Lysithea, the sleek design of the Tracers, or the genuinely alien look of the Tarsians themselves, there’s no lack of imagination or spectacle in the overtly sci-fi scenes. At the same time, however, there’s a blend of groundedness and the otherworldly that can be seen throughout, particularly through a playful use of lighting. Even when it comes to the more conventional backdrops, be it a classroom or the sidestreets of Noboru’s town (complete with passing trains), the beauty borne from glistening sunlight and screen reflections come off as strongly as the attention to detail. In motion, it could even be said to be memerizing, which really adds to the immersion. Granted, there are points, particularly where CGI is involved (such as with the mecha) when movements can seem choppy or somewhat rough, on top of the prevalence of still shots. For the most part, though, even considering that it’s (without hyperbole) done single-handedly, one would be hard-pressed to notice such issues compared to the rest of the imagery.

The audio isn’t one to scoff at, either. The soundtrack provided by Tenmon, which alternates between melancholy and ethereal (culminating in the song “Through the Years and Far Away” by Low), does a good job of conveying the mood. So much so that even the animation is synchronized with the music, resulting in a harmonious blend. This quality extends to the voice acting, at least in the Japanese dubs. Originally voiced by Shinkai himself and then-girlfriend Mika Shinohara, a professional dub track was recorded for the official DVD release, featuring not only Chihiro Suzuki and Sumi Mutoh taking the roles of Noboru and Mikako respectively and a then-rising singer named Donna Burke (her official YouTube channel) as the Lysithea’s unseen operator. Both versions do a solid job making the protagonists even more relatable to viewers. The same can’t quite be said of the English track, which comes across as more flat than anything else. Nonetheless, it’s an impressive effort.

Which isn’t to ignore Voices’ biggest, and arguably most memorable aspect: the execution. Much of what’s been mentioned would be commendable in isolation, but the OVA is truly more than the sum of its parts. Even with the static images at points, the anime makes the most of its runtime. In the span of less than an hour, it manages to incorporate (if a bit rushed) various disparate ideas, from space warfare and mecha to romance and slice-of-life, into a cohesive story. All this is achieved without sidelining the emotional weight or personal plight of the characters themselves. Such is the consistent focus on their pain, love, and determination against the odds, combined with how real Mikako and Noboru’s relationship feels, that it can tug at the heartstrings of even a cynical viewer. It’s little surprise, then, how the full package is not only poignant, but also timelessly so.

Through the Years and Far Away

Voices of a Distant Star is the kind of work that echos in one’s memory. It went on to win the 2002 Animation Kobe Award for “packaged work” and the 2003 Seiun Award for “Best Media,” as well as popular acclaim from anime fans, even across the Pacific.

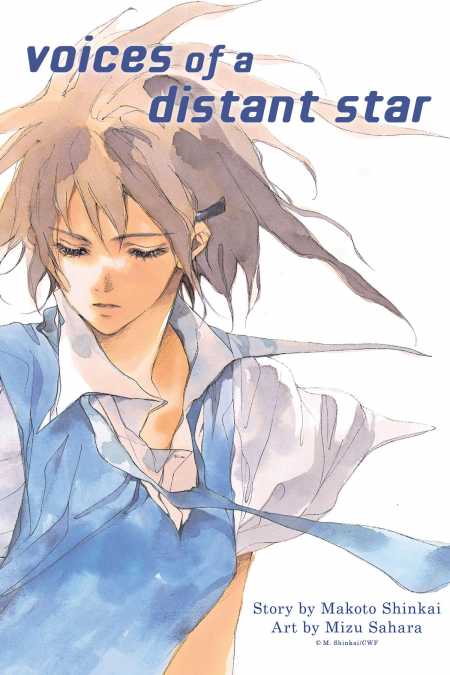

A drama CD was released in 2002, followed by a novel by Waku Ōba (with Makoto Shinkai as one of the illustrators) that same year. In 2004, the creator collaborated with mangaka Sumomo Yumeka (under her alias as Mizu Sahara) to write a serialized manga adaptation, which notably expounded upon the story (including additional characters and an extended ending) without sacrificing the same emotional impact of the original. This would be a recurring trend, later on, helped by the man himself being a manga artist and writer in his own right.

This isn’t to ignore how Voices of a Distant Star would come to help define Shinkai’s signature style. The use of lighting, focus on emotions, and a blend of the realistic and otherworldly to make even the most mundane seem extraordinary, have since been carried over, expanded upon and refined to an art in subsequent works, be it 5 Centimeters per Second (2007) or Weathering With You (2019). That they resonate not only with otaku or with audiences across Japanese society and beyond speaks multitudes to what modern anime is capable of.

Its legacy, indeed, could be seen outside his own work, even if indirectly. Kyoto Animation’s penchant for beautiful imagery and focusing on characters, for instance, rings familiar. Coincidentally, the man not only expressed support for the studio’s work, particularly on Sound! Euphonium the Movie: May the Melody Reach You (2017), but even praised the animators as “a group of people who have polished their skills in order to create great images for audiences to enjoy” in the wake of the arson attack that befell them. Meanwhile, it’s been speculated that the OVA may have been among Christopher Nolan’s inspirations for Interstellar (2014), especially with how the familial bonds between father and daughter across the space-time continuum in that movie echo Mikako and Noboru’s relationship.

To point out that Shinkai, for all his humility, has come far from those early days of relative obscurity isn’t hyperbole. Even now, Voices of a Distant Star still manages to remain poignant and touching. Whether as a testament to sheer ability and determination, or as a timeless, haunting love story, it’s bound to leave a lasting memory.