The story of how the 1970s series Voltes V came to be embraced in the Philippines and foster the country’s fandom for Japanese works in the process, is as fascinating as it is peculiar. Indeed, it seems like the sentiment is mutual, given the growing interest in Filipino culture in Japanese works. Just as interesting, however, was the next wave of anime to hit local airwaves in the 1990s, and how an unlikely show, known as Ghost Fighter, helped solidify the local otaku community as a popular mainstay.

To understand the significance, you have to turn the clock back nearly three decades.

Superstition Aplenty

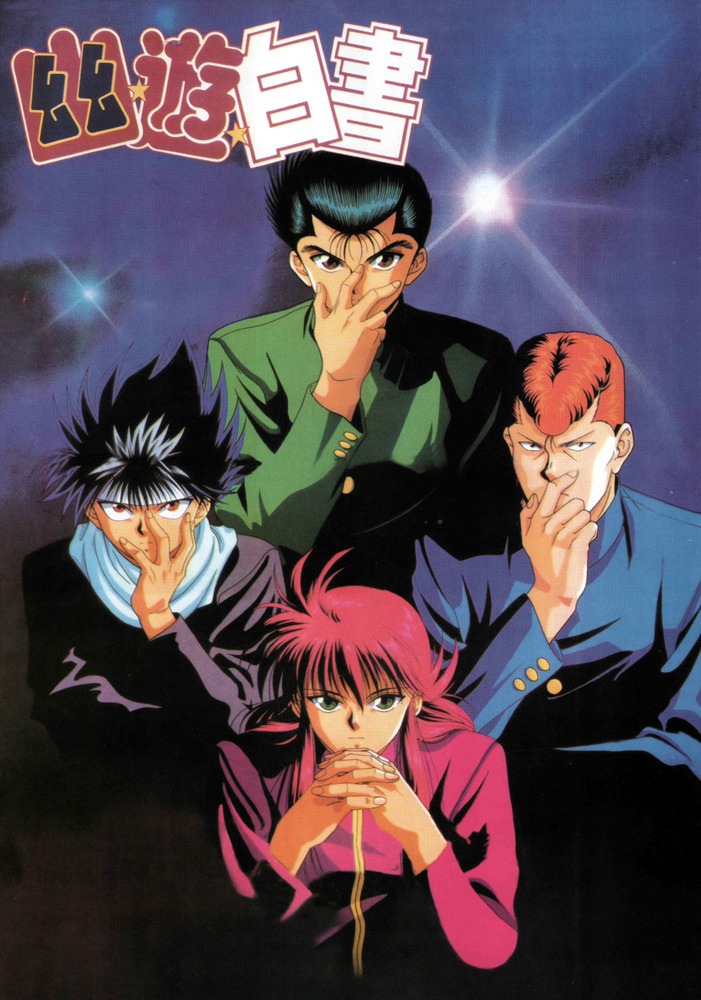

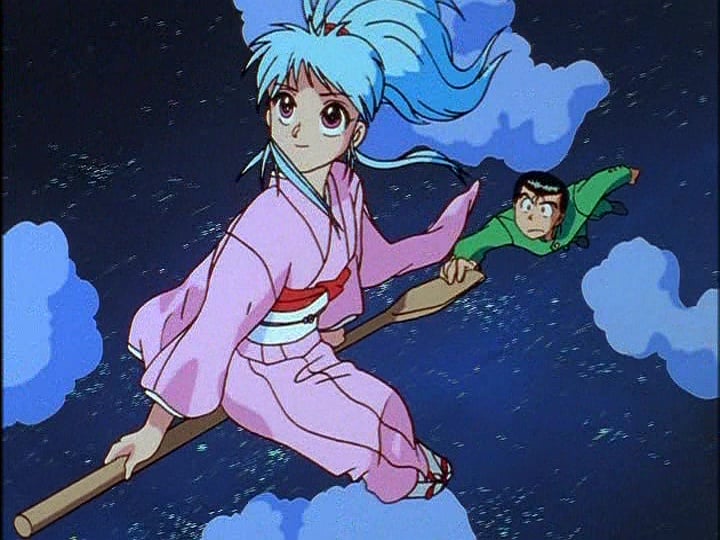

Trailer for the Filipino dub of Ghost Fighter for GMA-7. Circa 1998.

The early 1990s were rather tumultuous for the Philippines, marked by power outages, earthquakes, and the infamous 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo. Yet those years were also a time of great opportunity, as Filipinos at large sought to make their name as a rising tiger in a changing landscape. Indeed, with the media censorship of the Marcos administration long since abolished, it seemed like the world itself was at their fingertips.

It’s no surprise, then, that fresh from the renewed popularity of shows like Voltes V, all kinds of anime were being brought to living rooms, whether on local networks or through nascent cable TV. Compared to the 70s, however, the selection was far more varied. Whether it was religious fare like the early 80s show Superbook, historical dramas such as Princess Sarah, or instant hits like Dragon Ball and Sailor Moon, there pretty much was something for everyone. Amidst this came an adaptation of a Shonen manga by Yoshihiro Togashi: Yu Yu Hakusho. Filipinos know it better as Ghost Fighter.

Directed by Noriyuke Abe (of Flame of Recca, Great Teacher Onizuka, and Boruto fame) and produced by Studio Pierrot, Ghost Fighter originally aired in Japan from 1992 to 1994 (114 episodes in total). Two movies and a six-episode Eizou Hakusho OVA miniseries were also made in the 1990s, with two more OVAs based on the manga (Two Shot and All or Nothing) coming out in 2018. Meanwhile, the localized broadcast, dubbed into Filipino, first appeared on state-run network IBC-13 around the mid-90s, before being taken up by GMA-7 in 1998.

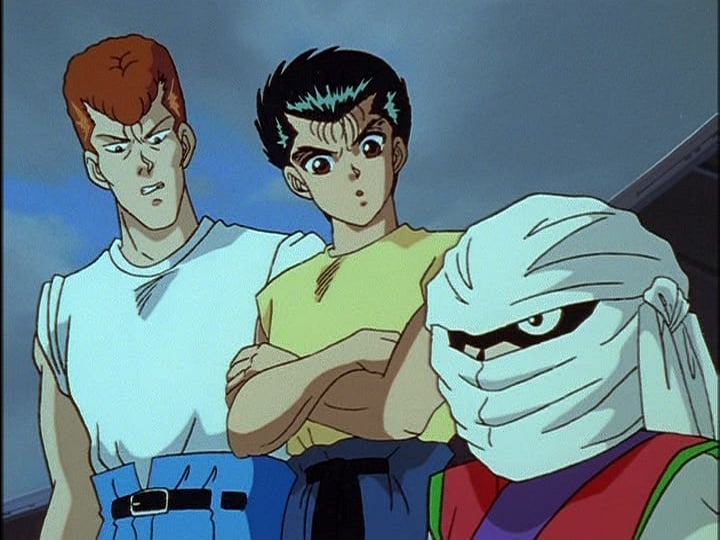

The long saga follows the trials and exploits of Yusuke Urameshi, a teenager who dies in a car accident while saving a child. After being tested in the afterlife by its leader’s son, Koenma, he’s brought back to life as a supernaturally endowed “Spirit Detective.” Together with his best friend, Kazuma Kuwabara, the cryptic demon Kurama, and the demonic swordsman Hiei, along with a motley gang of allies, he faces myriad threats to all the worlds on a regular basis, clinging on to his humanity against all odds.

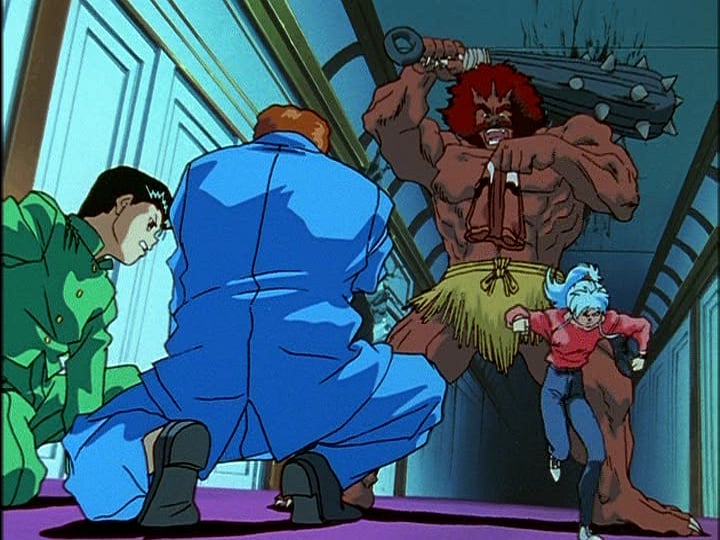

Echoing the treatment of Voltes V and Daimos, much of the cast had their names Westernized. Yusuke, for instance, became “Eugene,” while his mentor Genkai was renamed “Master Jeremiah.” Hilariously, the evil Team Gorenja members from the “Dark Tournament” saga were somehow redubbed the “Power Rangers” due to their colored belts, whereas the more memorable villain Toguro retained his name, albeit as “Taguro.” More than the localization choices, however, what makes the anime peculiar is that there seems to be little for Filipinos to relate with. While the series is known for its tournament arcs and martial arts action, it also takes heavy inspiration from Buddhism and Japanese folklore, with some sprinklings of occultism and Greek mythology. The resulting universe couldn’t be any farther from the sort of symbolism that’d resonate with a predominantly Christian culture.

From an outsider’s perspective, then, Ghost Fighter may appear to be a very unlikely choice for one of the most popular anime in the Philippines, but looks can be deceiving.

Found in Translation

Despite the seemingly alienating premise, there’s much that Ghost Fighter does that leaves viewers wanting more every time. For one, there’s the worldbuilding. As brash as “protagonist dies in the first episode” may be, the anime goes to some lengths to ease you into the setting, from the blend of modern technology and traditional styles in the Spirit World, to the otherworldly threats lurking in the Demon World. Along with how mystic powers are shown throughout (such as Eugene’s “Spirit Gun”), the result is a universe that feels natural, with its own consistent rules. There are even formal classifications of demons, spirits, and humans based on their powers. That Filipino folklore, even after centuries of Christianization, retains a similar emphasis on mysticism and fantastical creatures (including creatures like diwata) also means that there’s more of a resonance among the audience than at first glance.

The characters themselves, whether they’re human or demon, are likewise interesting to watch. The leads alone are shown to be more than meets the eye. Eugene, for instance, starts off as a classic Shonen delinquent. Over the course of the series, however, he not only struggles with demons but also with issues that teenagers would find relatable, be it confessing to a girlfriend or finding your place in life, which also play into subplots later in the story. Notably, he matures over the course of several episodes while still retaining brash, yet caring. This extends to both heroic characters, such as Hiei/Vincent opening up and being genuinely helpful, and villains alike, with Taguro in particular shown to be more of a tragic “fallen hero” amidst his quest for power. That a good deal of characters generally tend to look easy on the eyes, including Master Jeremiah’s younger form, is a bonus.

Then, there’s the actual writing and execution. True, Ghost Fighter is known for its action setpieces, of which there are many. At the same time, the anime is also known for having plotlines that, even at their most out-there moments, remain grounded. Take the “Chapter Black” saga, for example. Second only to the Dark Tournament plotline in terms of length, this centers around Eugene’s efforts to stop Sensui, a former Spirit Detective, and his comrades from ending the human race. It also involves the titular artifact, a mystic VHS tape containing records of all the atrocities and sins committed by mankind and turns anyone who sees it to nihilism. While it’s revealed later on that the notorious tape was never intended to be viewed alone, much of the conflict stems from whether humanity deserves to be saved, even when faced with the worst of the abyss. On top of presenting Sensui as a dark mirror of what the hero could have become, it also has viewers questioning who’s right.

Needless to say, Ghost Fighter at that time offered more than enough to satisfy Filipino viewers. While a good deal of them were likely the children of those who grew up watching the Voltes V, many of them were also newcomers wowed by an art that seemed to resonate with them more than most Western works. Word of mouth, schoolyard play, TV reruns and, eventually, Internet memes took care of the rest.

Spirit Power

It’s no surprise that Ghost Fighter has consistently remained one of the most popular classic animated shows in the country. One need only type those words on YouTube to find all kinds of videos involving the Filipino dub, complete with episode compilations that have over a million views; even if newer generations tend to recognize the anime by its original name of Yu Yu Hakusho, old habits die hard. If you’re lucky, you may even find jeepneys or other public transportation with fanart proudly on display.

Granted, the show doesn’t have the same historical weight as Voltes V does. Nonetheless, alongside its peers and runaway hits such as Pokémon, it played a major part in allowing the seeds planted back in the 1970s to grow. Indeed, it wouldn’t be much of an exaggeration to say that the adventures of Eugene and his friends have helped make otaku culture in the Philippines anything but a passing fad.