When it comes to other countries adopting or incorporating Japanese styles into their works, it’s tempting to say that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Bolivar el Héroe (2003), an anime from Colombia, is proof that this isn’t always true. If anything, it’s an almost textbook example of how not to do an homage, whether to the cultural inspiration or the subject matter.

Running at 75 minutes, it’s the brainchild of one Guillermo Rincón, a Colombian director who evidently cashed in on how anime and manga were (and remain) popular across the Hispanosphere. Just as the man faded into obscurity not long after its release, so did the movie itself for a time, to the point that it became something of an urban legend. It wasn’t until 2015, however, when a Mexican dub of the film was uploaded to YouTube, that it gained its current notoriety not only throughout Latin American circles, but across the globe.

A recording of the movie’s trailer, giving viewers a taste of what to expect. It’s also an early indication of the film’s existence, years before the full version found its way online. Circa 2012. (Source: YouTube)

Beyond the Spanish memes, it’s tempting to think, “It can’t be that bad.” The reality is more disappointing.

Simon’s Bizarre Adventure

As the title suggests, Bolivar el Héroe is based on the exploits of Simon Bolivar: the famed revolutionary who led the push for independence against Spain in the early 19th Century. More specifically, the film covers his origins, and how he went from being a child of the aristocracy to becoming El Libertador (“The Liberator”), as he’s fondly called across Latin America. One would be hard-pressed, however, to call the anime true to life.

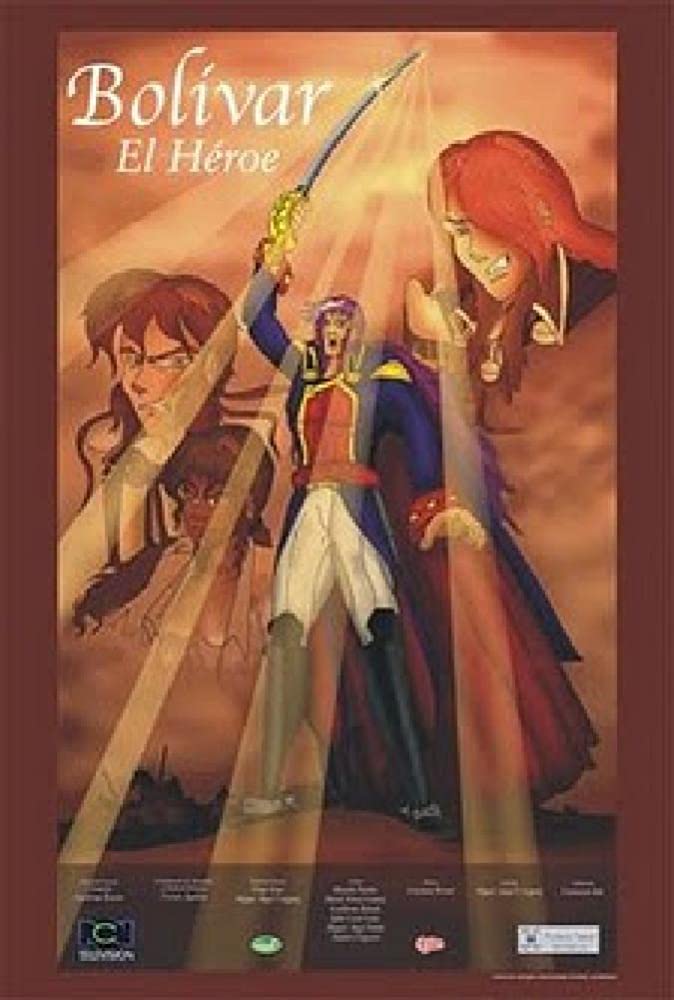

The quality of the visuals alone is a telltale sign. Almost from the get-go, you’re treated to what could only be described as a mangled blend of various styles, seemingly invoking Saint Seiya and the earlier volumes of JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure. Bolivar himself is even made to approximate a Shonen protagonist (complete with purple hair and a fiery aura), with many of the African slaves, such as Américo, looking similarly heroic and hot-blooded. In practice, though, the movie fails completely in emulating the Japanese aesthetic, whether it’s side-characters having inconsistent and ugly art (some barely resembling people at all), the plasticity of the coloring, or how the designs themselves generally look like they’re ripped out of a bad “how to draw manga” guide. It’s even worse when they actually move, whether due to stilted and poorly looping animations, the atrocious special effects, or how outright lazy things can get (with figures sliding into frame). Chances are, you’d find more in common with the Zelda CDi cutscenes or anything from Dingo Pictures than anime. All the while showing more bloodshed than what you’d expect for something obviously aimed at children.

It’s not as though the actual content of the film compensates for the horrid sights, either. Although the broad strokes of Bolivar’s life up to the wars of independence are covered, you don’t need to be an expert in Latin American history to see how the titular El Héroe‘s story is distorted. His childhood, for instance, is made out to look like a ripoff of Phantom Blood, including a rivalry with a bigoted and unlikeable antagonist named Tiránico, who’s confronted later on as the embodiment of Spain’s imperialism. In addition to simplifying the context of the era to an insultingly moronic level (with said villain made to be as cartoonishly evil as possible), there are also aspects of the protagonist which were either rewritten or outright made up. He certainly never had a cliched romance with his enemy’s sister, while his tragic love affairs, in reality, were never so much as alluded to. Nor did he actively make fighting slavery and racism a key point in his struggle (represented by Américo) until later on, or at least not to the near-absolute levels on display. As a consequence, you only get a dumbed-down caricature, devoid of what truly made him great. Libertador (2013), this is not.

The only saving grace, perhaps, would be the performances, at least in the version online. For reasons still unclear, a dub was made with Mexican voice actors following the original Colombian one; though the original track is now lost to time, it’s known that both shared the same narrator, Luis Carlos Zabala. Either way, you don’t have to be knowledgeable in Spanish to notice how dissonant the acting can be, due to how solid it is in contrast to the horrid imagery. It only adds more questions as to what the circumstances were behind the anime’s creation and eventual fall into obscurity.

A Revolution of Failure

Whether in English or Spanish, there’s little in the way of publicly available information surrounding Bolivar el Héroe itself. From what could be gleaned, it not only saw a theatrical release in Colombia (with an initially decent showing at the local box office), and subsequent airings on both national and regional TV channels. The anime had also, according to Wikipedia, been screened at a number of film festivals across Latin America, with the last recorded case being in Guadalajara, Mexico, in 2007. Meanwhile, according to a televised interview with Rincón from 2003 (which coincidentally contains the only known footage of the original dub and actual production), it took four years to make, and was comprised of 130,000 frames done through computers and técnica Japonesa (“Japanese technique”). There were even plans for a sequel.

You could tell, nonetheless, that based on what’s survived, the movie was a mess behind the scenes. Archived forum posts from around 2004 suggest that there was some infighting over who ought to take the credit. While private messages given by one of the producers, Miguel Ángel Vázquez, to YouTube channel Animación Artesanal in 2015 confirmed Rincón’s involvement as the director, it’s also revealed that the production was self-financed without subsidies from the Colombian Ministry of Culture, costing about USD 70,000. Given the end results, it’s highly unlikely that the creators ever recuperated the money. Nor do the meager funds (even compared to an average anime episode) justify the sub-par dumpster fire display.

It speaks volumes that the parodies made tend to be better done, and more faithfully anime, than the source material itself. Circa 2015. (Source: YouTube)

It’s no wonder that this piece of work got so notorious that it became something of a national embarrassment, instead of the love letter to Bolivar and anime it was ostensibly intended to be. That it’s so bad it couldn’t possibly be real even likely contributed to its momentary perception as a myth or urban legend. Since the rediscovery of the Mexican dub in 2015 and subsequent mirroring online, however, it’s found its place among Latin American otaku, as well as others around the world, as fodder for memes and ridicule.

All things considered, there are worse fates out there.