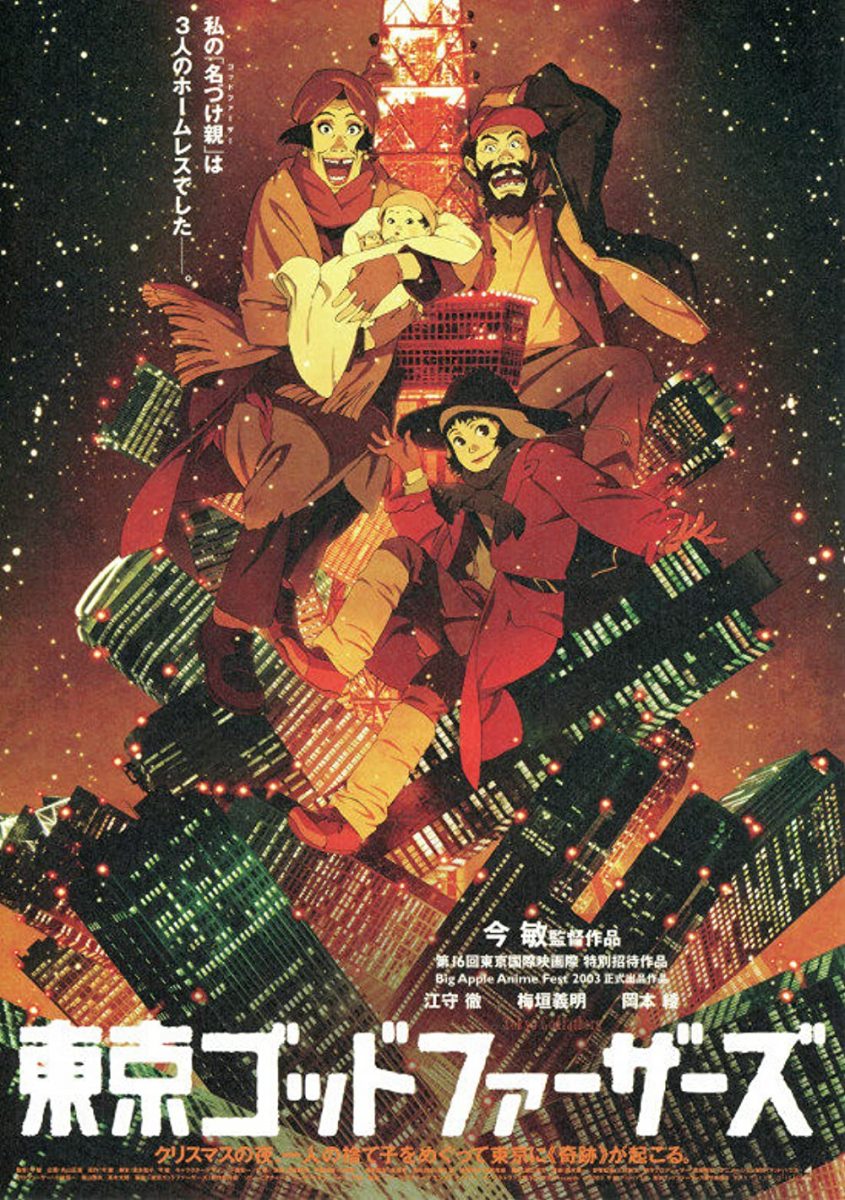

It seems like many countries have their own takes on the classic Christmas film or special. While Japan isn’t an exception in that regard, it’s not lacking in unique works or anime set around the Yuletide season. One that stands out, however, would be the late Satoshi Kon’s Tokyo Godfathers (2003). Even now, it says a lot how a seemingly jarring mix of influences and elements featuring three homeless people could mesh well together to become a 21st Century classic.

Created by anime production giant Madhouse and co-written by Keiko Nobumoto (of Wolf’s Rain and Cowboy Bebop fame), it doesn’t take too long into the 1:32 hour-long runtime to see why it has since garnered critical and fan praise. Moreover, despite its seemingly gritty exterior, there’s much here that manages to transcend cultural boundaries while remaining recognizably Japanese. Though what better way to find out than to actually see it for yourself?

The trailer for the film’s remastered cut does a good job showing just how well the visuals have held up from 2003, as well as the unique if jarring tone. Circa 2020. (Source: YouTube)

A Different Winter Wonderland

Taking inspiration from Peter B. Kyne’s 1913 novel The Three Godfathers, Tokyo Godfathers follows a trio of homeless people in modern-day Tokyo: Hana the transvestite woman (Yoshiaki Umegaki, Shakina Nayfack, Russell Wait), Gin the chronic gambler (Tôru Emori, Jon Avner, Darren Pleavin), and teenage runaway Miyuki (Aya Okamoto, Victoria Grace, Candice Moore). One Christmas Eve, they stumble upon a healthy newborn baby while rummaging through the trash. Deciding to return the newborn to their rightful parents, they find themselves in various misadventures. As they stumble from one part of the Japanese capital to another, however, they also find themselves in more than a few, almost miraculous coincidences.

From the get-go, you’d notice that the anime makes several deliberate choices that make it stand out from other mainstream fares. One of them is how the film’s seen through the eyes of hobos and those outcast by wider society. Rather than the Tokyo portrayed in tourism ads or with glitzy flair, for instance, the megalopolis is portrayed, warts and all, from soup kitchens to the sleek skyscrapers that seem eternally out of reach. Each of the protagonists also struggles with personal demons reflecting elements of post-Lost Decade Japan that weren’t spotlighted at the time as anime material, be it gender identity, gambling addiction, or familial strife. It’s the kind the backdrop that would lend itself to political polemics or inspiring some grim crime novel. Yet despite that, as well as how tense some of the situations can get, it’s remarkably upbeat. In turn, lending a kind of slice-of-life atmosphere that further makes the characters all the more relatable and sympathetic.

The use of modern Christianity and other foreign touches are also especially prominent, and not just in terms of adopting the 1913 novel or side-characters who speak fluent Spanish. Angels and Biblical references are recurring motifs, be it the Nativity reenactment at the beginning of the movie, or the myriad advertisements and decorations scattered throughout the city. The various situations that the trio and their baby find themselves in, as well as the ridiculously close shaves with death, also call to mind the kind of coincidences you’d expect in a Home Alone movie. And just like such flicks, there’s just enough to suggest that those may or may not be miraculous, in classic Christmas tradition. For all the worst the world can give, there’s always that one gesture of kindness or glimpse of hope that makes humanity the way it is.

It’s clear that Kon and Nobumoto had done their research. In doing so, they not only transcend borders but also make tropes familiar to Western audiences relatable to Japanese ones without belittling either, as seen how the aforementioned Nativity scene is juxtaposed later on with more traditional Buddhist and Shinto worship. That in itself is rather impressive, especially coming from a non-Christian nation. What further elevates it, however, would be the execution.

Counting Blessings

What Tokyo Godfathers does especially well is how it brings the titular city and those living there to life, often with paradoxical contrasts. The art style is decidedly realistic, with grimy details on the impoverished hobos and often muted color palettes. At the same time, however, there’s an almost whimsical feel to the surroundings at times, whether it’s the warm glow of a convenience store, the almost overwhelming flair of a wedding reception, or how consistently radiant the Christmas imagery can be. This holds up even when in motion, especially in how the characters move about convincingly and emote with similar, yet vivid candor. You can tell with each look of anguish, or the grin whenever Hana holds the baby, that the animators put a lot of love into the film.

Much the same could be said for the sounds. The voice acting, whichever language you prefer, matches the characters they’re portraying, the cast’s performances being simultaneously subdued, realistic, and very manic. Meanwhile, Keiichi Suzuki and the Moonriders provide a soundtrack that combines influences as varied as Yuletide jingles, Western rock, vintage jazz, and traditional melodies to deliver something that couldn’t be pinned down to any single genre. In themselves, they can come off as jarring as the juxtaposing of both serious and upbeat moments. Yet the result is genuinely much more than the sum of their parts, which says a lot about Kon’s skills as a director.

It’s little wonder, then, that the movie has garnered critical accolades internationally, including the 2004 Neuchâtel International Fantastic Film Festival. Even as recently as the 47th Annie Awards in January 2020, the late filmmaker was posthumously recognized for his long, storied career in the industry. Among fans of either his work or Madhouse, it also comes as a little surprise that it’s gained a considerable cult following. That the story, visuals and general presentation still hold up well further give a timelessness that’s reserved for the likes of Home Alone.

While one could only imagine what Kon might have made had he still been alive, or what he could have done with the material in Tokyo Godfathers, it’s not hard to see why more than a few commentators online remark that it’s arguably one of the best Christmas anime ever made. What better way to close the year on a better note?